Scaling Through Chaos

The Founder’s Guide to Building and Leading Teams from 0 to 1,000

Foreword

You’re reading this book. But are you sure you want to?

Living through high-growth is highly uncomfortable. And it should be. Founding a startup that scales rapidly is not a common path. If you choose to walk it, you’ll be breathing rarefied air.

We haven’t written Scaling Through Chaos to make the journey easy for you. No one could do that. But what we can do is systematically break down twenty years’ worth of data and insights into how the world’s fastest growing and most successful startups have scaled the mountain, taking the kernel of a crazy idea and turning it into a highly impactful company.

We’ve designed this book and its companion app to be a toolkit for the world’s most ambitious entrepreneurs. We know they—you—are hungry for actionable, evidence-based advice, of the kind you’ll find in the other books in the Index Press series: Rewarding Talent, Winning in the US.

Here, we’re focused on helping you figure out how to find, hire, retain and lead the right people to turn your business into an outlier success. Scaling Through Chaos is packed with original case studies, fresh frameworks and unheard stories about the inner workings of pioneering startups. It’s based on the most extensive research ever performed into the growth of VC-backed businesses—incorporating analysis of 200,000 career profiles at 210 companies, in and beyond the Index portfolio.

What you’ll take from this book depends on the particular challenges you’re confronting. How do you manage hierarchy and process without squashing creativity as you grow? What’s the best way to structure your tech team? How can you make the most of your network without building a monoculture?

There’s no recipe or blueprint for how to innovate. But certain things are tried and tested. What this book gives you is a set of best practices and shortcuts about how to hire people, how to stretch them, how to organize them—all of which helps you achieve scale faster. It relieves you of the mental burden of reinventing the wheel of people management, so you can play with the stuff that demands creativity—things like product, growth and technology. It frees you up to innovate where it matters.

The core message of Scaling Through Chaos is that disorder is the price of transformative progress. Try to stamp it out, and you’ll kill what’s special about your company. The most successful founders accept that discomfort, change and evolution are part of the journey, and that the people who help you get from zero to one aren’t necessarily going to get you over the line at the end. You want to back and support your team, but you also have to value and reward performance over loyalty.

You also need to look ahead, while accepting you’ll always be behind where you want to be. In high-growth, you can never hire and onboard quickly enough to match the demand you’re seeing, and it always feels like you’re filling gaps. Yet you have to get your head above the waterline to be able to look to the next beachhead, the next blocker, the next opportunity that’s 12 months or more down the track.

What you’ll see in this book is that growth is not linear, nor even a hockey-stick. Every single successful company has been through at least one near-death experience. No one goes from strength to strength, and often you need to retrench, regroup, pick yourself up and begin again. The key traits of successful founders are not only brains and brilliance, but also commitment and resilience—waking up every day and giving 200% of themselves, solving impossible problems and starting to see obstacles as learning moments. The best entrepreneurs find ways of getting energy from overcoming difficulty.

Expect to make sacrifices. To scale through chaos, you’ll need to pour your life into your business for at least a decade. It’s not for everyone, and it’s not the only way to be successful in life, business or entrepreneurship. But for those willing to step up, there are immense rewards too. If you choose to ride the rocket, Scaling Through Chaos can help you handle the turbulence.

Martin Mignot,

on behalf of Index Ventures

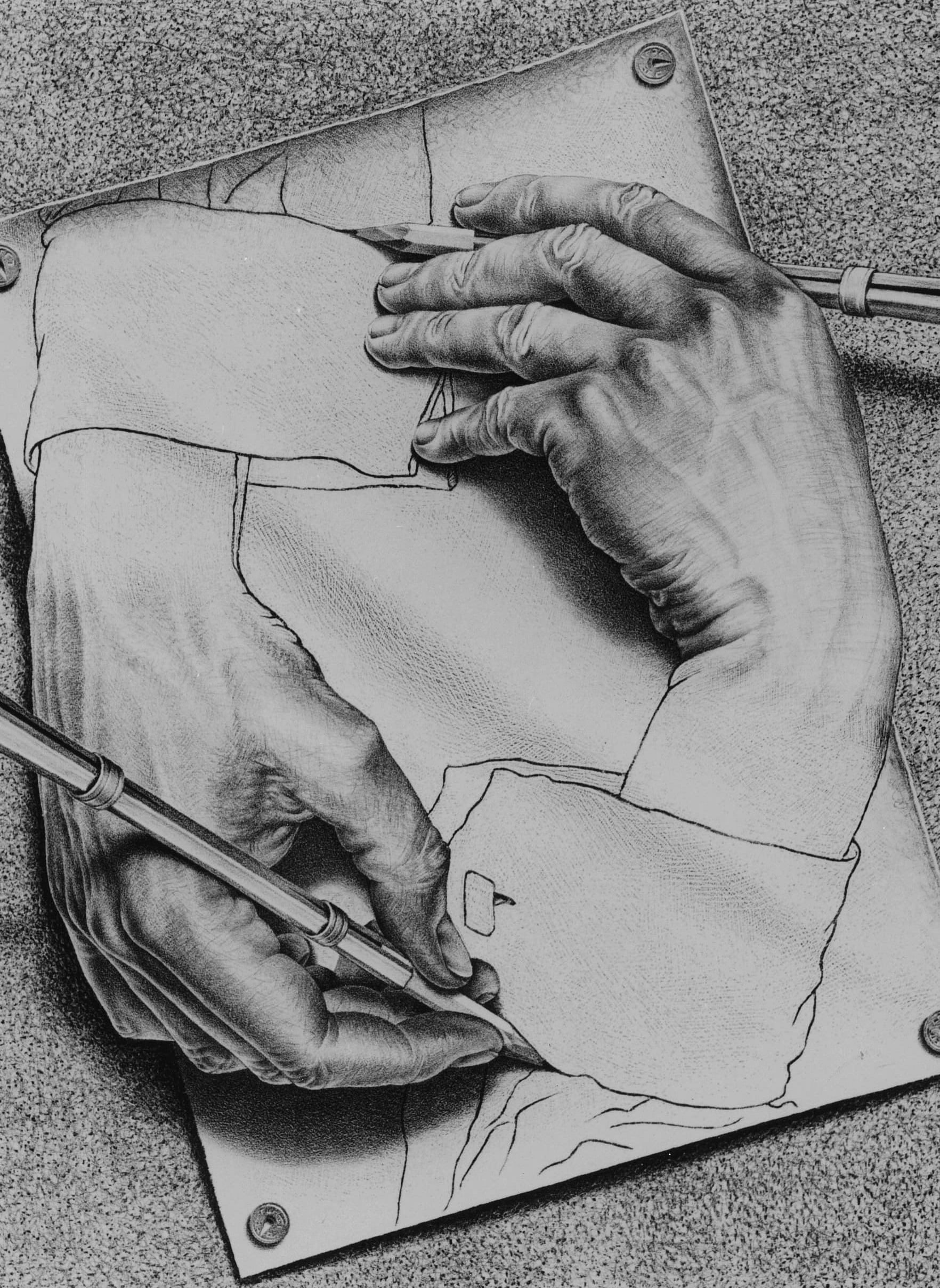

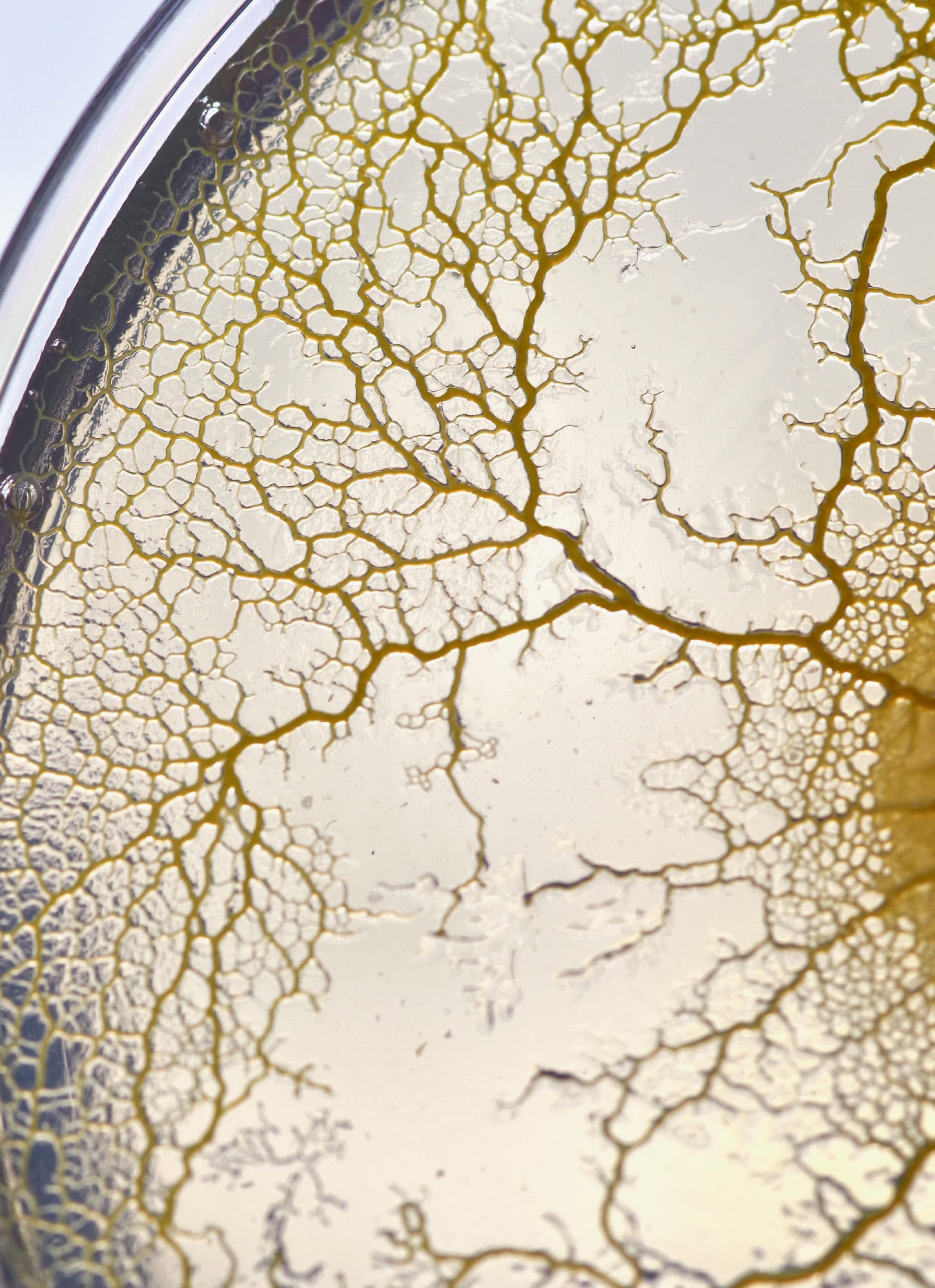

Growth is messy, as any parent can tell you. When organizations grow rapidly, they too become more complex and unpredictable. But often there’s order hiding beneath the turmoil. When you open your eyes, you can find parallel examples of emergent structure and beauty all around us—in nature, art, mathematics and society. With a clarity of purpose and the right people on board, companies can find a dynamic equilibrium that rolls with the chaos but channels it towards success, resilience and creativity, with minimal top-down control.

Beauty in chaos

In 1975, a brilliant young physicist Mitchell Feigenbaum made a startling discovery, after working for 22 hours a day for two solid months. A number kept cropping up in systems that circle around an average state for long periods of time before collapsing into chaos—behavior typical of storms, the stock market and even the human heart during cardiac arrest.

This universal magic number—approximately 4.6692—is now known as the Feigenbaum constant. It describes with uncanny precision the ratio between bifurcations in dynamical systems, and allows us to estimate when they will flip between order and chaos.

Feigenbaum’s constant is one of the defining discoveries in the history of complex systems, helping to account for everything from the shapes of mesmerizing fractal structures like Romanesco broccoli to the growth of human populations. It shows how simple principles can give rise to forms that are at once bewilderingly complex, beautiful and elegant—and how order can exist beneath the appearance of turmoil.

Stories of Chaos

How to surf the edge of chaos

It's all about people

Founders are fired up by the desire to make a positive difference to the world, by honing in on a significant pain point that people experience. They identify how technology offers new solutions to old problems. Through months or years of ideation and bootstrapping, their customers’ needs and product iterations end up consuming most of their waking hours.

Founders spot a big wave and become obsessed with making the surfboard to ride it.

Jan Hammer, Index Ventures

As a consequence, founders are often shocked to discover that, once you have a minimum viable product (MVP) and venture funding, the majority of your time quickly becomes absorbed by hiring, HR and people management. These areas present some of the toughest challenges that you’ll ever face as an entrepreneur trying to build a high-performing organization. To rise to the occasion, you need to embrace a mindset shift from “building a product” to “building a team and a business based on the product”. Your overall time commitment to people-related matters will come in waves rather than being constant, but it won’t drop away as you scale.

The epiphany for me has been realizing that building a great company relies most on leveraging people rather than strategy. Successfully opening a new office isn’t about analyzing a budget spreadsheet—it’s about who will lead it.

Tom Leathes, CEO & Co-Founder, Motorway

The disconnect between founder expectations and reality was a major reason we created this handbook. We know that founders can come from anywhere, and there’s no template guide for becoming an exceptional entrepreneur. Outlier companies are, by definition, built by people willing to make outlier decisions. Yet beneath the chaotic swirl of global startup activity, patterns rise to the surface—patterns that can help entrepreneurs grow their own thriving, and even iconic, businesses.

If you’re a founder who’s ever wanted to know how companies like Airbnb, Figma and Stripe got to where they are today, this book is for you. To set you and your startup on the best possible path, Index has carried out the most extensive research to date into how tech startups with venture funding scaled their teams to build amazing companies. We’ve created and studied a dataset of over 200,000 founder and employee career profiles to map out the journeys of 210 of the most successful tech companies ever built.¹ The insights in this book draw on this dataset, including more than 150 graphs and tables. We’ve enriched this analysis based on our own experience as investors over the past 25 years, supporting more than 400 current and former companies in our portfolio, and by conducting interviews with 60 founders and highly regarded functional leaders.

¹ The analysis in this book covers four business models: SaaS, Marketplace, B2C App and D2C e-commerce. The US represents 70% of the chosen companies with the remainder mostly from Europe. For each of these companies, we compiled the anonymized profiles of all individuals hired, categorizing 9,000 job titles into 16 functions, 29 sub-functions, and five managerial levels. We then analyzed individuals’ roles, joining dates, where they had worked and studied before, and how long they stayed, as well as their internal promotions and moves.

Selection of the founders and operators we interviewed.

Discord

Jason Citron—CEO & Co-Founder

Clint Smith—Chief Legal & Safety Officer

Wiz

Assaf Rappaport—CEO & Co-Founder

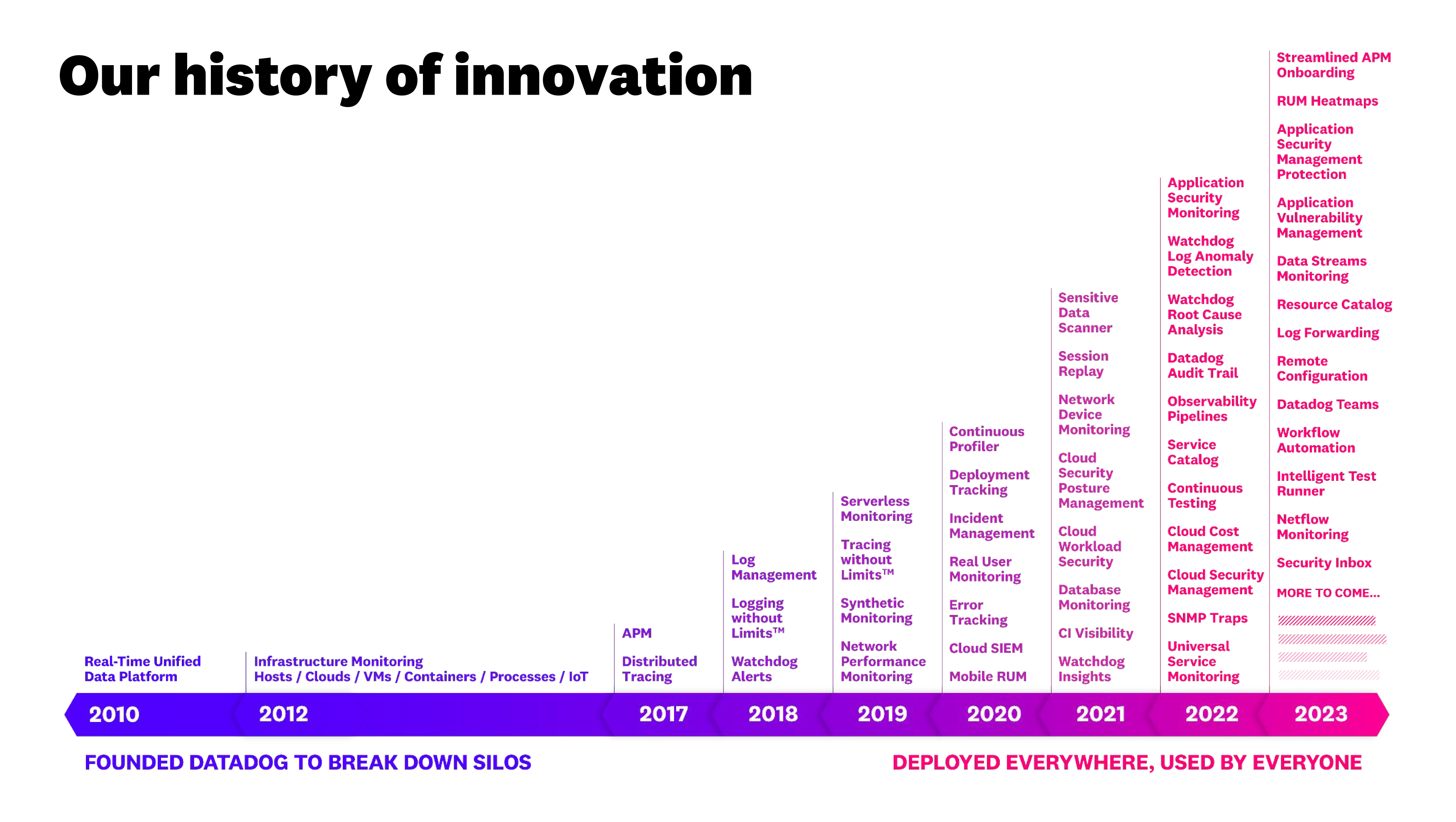

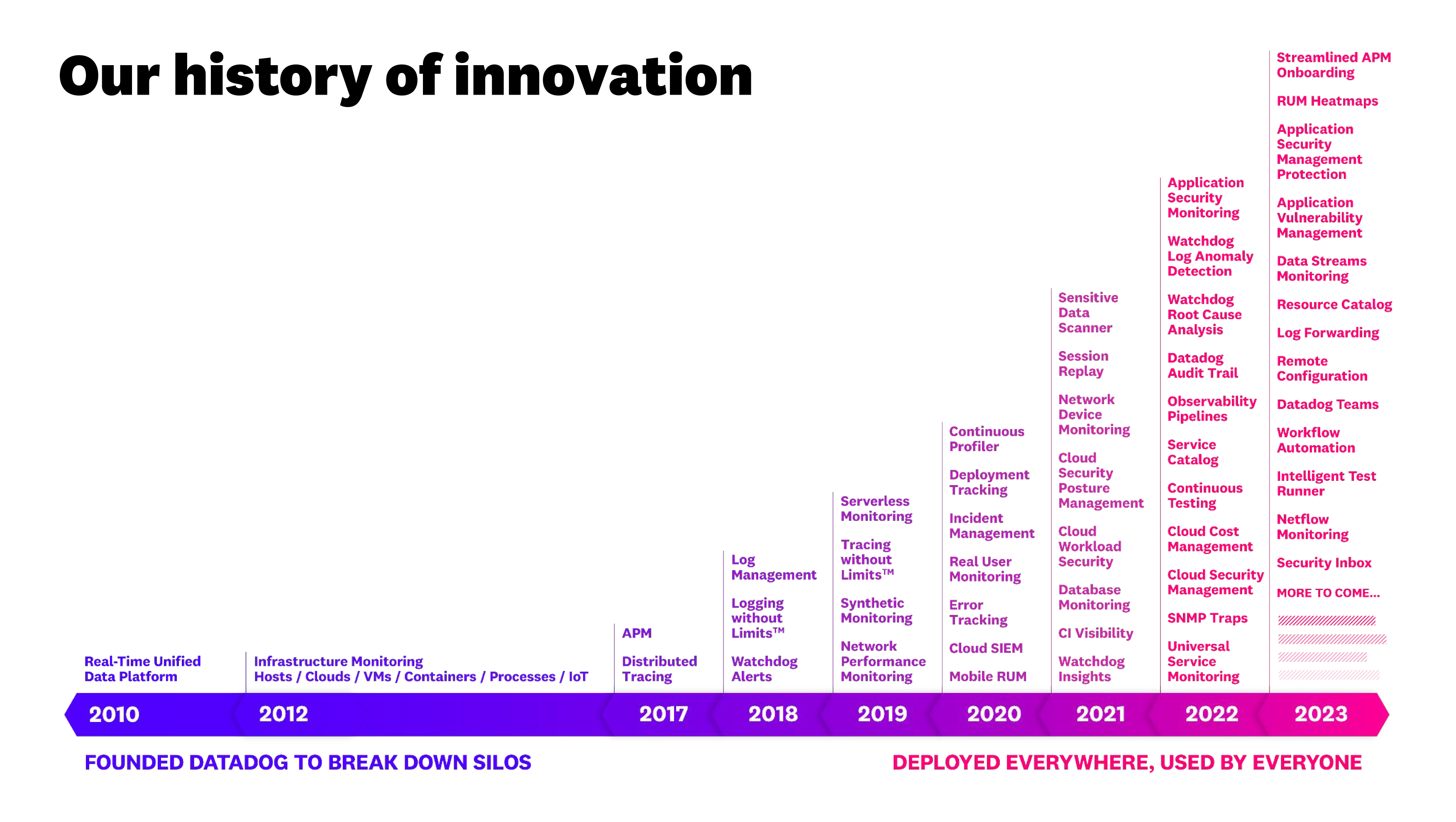

Datadog

Alexis Lê-Quôc—CTO & Co-Founder

Figma

Nadia Singer—Chief People Officer

Amanda Kleha—Chief Customer Officer

Maven

Kate Ryder—CEO & Founder

Gong

Amit Bendov—CEO & Co-Founder

Personio

Hanno Renner—Co-Founder & CEO

Jonas Rieke—Co-Founder & Chief Operating Officer

Maria Angelidou-Smith—Chief Technology & Product Officer

Ross Seychell—Chief People Officer (former)

Remote

Job van der Voort—CEO & Co-Founder

Sam Ross—General Counsel

Notion

Michael Manapat—Chief Product & Technology Officer (former)

Hubspot

Kipp Bodnar—Chief Marketing Officer

Robinhood

Surabhi Gupta—SVP Engineering (former)

Snap

Farnaz Azmoodeh—VP Engineering (former)

Plaid

Paul Williamson—Chief Revenue Officer (former)

Squarespace

David Lee—Chief Creative Officer

Raphael Fontes—SVP Customer Operations

GOAT Group

Yunah Lee—Chief Operating and Finance Officer

Farfetch

Andrew Robb—Chief Operating Officer (former)

Sian Keane—Chief People Officer

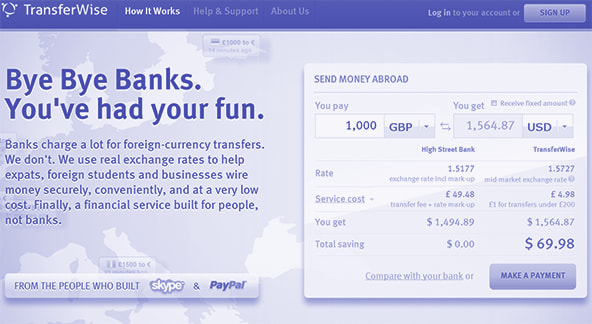

Wise

Harsh Sinha—Chief Technology Officer

Joe Cross—Chief Marketing Officer (former)

Spring Health

Joanna Lord—Chief Marketing Officer

Revolut

Antoine Le Nel—VP Growth

Confluent

David Perry—VP Europe (former)

Full list of the 210 highly successful companies we analyzed.

SaaS

Marketplace

B2C Apps

D2C E-commerce

TeamPlan—the companion web app to the Scaling Through Chaos handbook

TeamPlan is Index Ventures’ groundbreaking new tool that allows founders to benchmark their team’s growth against the headcount journeys of these 210 highly successful tech startups, across 14 separate functions in Technical, Go-To-Market (GTM), General & Administrative (G&A) and Operations. How big was the engineering team at 50 headcount, and how did it split between backend, frontend, mobile, testing and developer operations (DevOps)? How many companies had a CFO by 250 headcount? How much team attrition was there between 51 to 125 headcount? TeamPlan helps you answer these questions and more, filtering companies by business model and customizing the visualizations to uncover detailed insights into team scaling, structure, hiring and leadership. TeamPlan is free to use.

At Index, we believe that people are everything, and we spend a lot of our time making sure our founders work with the best possible teammates. But we also know how hard it is to manage a team when you’re in high-growth mode. Our data shows that if you’re scaling up as a highly successful startup, you’re likely to double your headcount year-over-year during four or more successive years. It follows that half your employees will have been with you for under one year at any point in time, which generates massive organizational stress.

A certain level of chaos is healthy.

Lindsay Grenawalt, Chief People Officer, Cockroach Labs

You can pick the most successful high-growth company in the world, and insiders will still say it’s a shitshow.

Andrew Robb, COO (former), Farfetch

You want to surf the edge of chaos, with just enough process to stay upright, but not so much that you can’t flex to catch a passing wave.

Dominic Jacquesson, Index Ventures

We chose the title Scaling Through Chaos in recognition of the inevitable tumult involved in scaling teams through times of rapid company expansion. Like the non-linear systems that are the focus of the mathematics of chaos theory, the complexity of a startup increases exponentially with its size. Its behavior and output can be extraordinary, but also wildly unpredictable. The key challenge, we believe, is to surf the edge of chaos: You want to introduce people, processes and systems adapted to your particular stage of growth so that everyone is aligned and motivated, without quashing the agility and energy that carried you this far. Finding this dynamic equilibrium at any point in time requires flexibility and constant reinvention.

You hit breaking points where you need to actively evolve to succeed at your next stage of scale.

Nadia Singer, Chief People Officer, Figma

How to get the most from this book

This book is neither a manual nor a set of must-do prescriptions. There is no single recipe, no blueprint, for how to build a high-growth business. Yet over our decades of experience in nurturing some of the world’s most successful tech companies, Index has developed unique insights and robust frameworks that reveal what works, and what tends not to. We present this book as an opportunity to learn from how other extraordinary companies approached decision-making. Where there are disagreements and varying points of view, we highlight them.

You’re unlikely to want to read this book from start to finish. Instead, we advise you to use it like a reference resource, dipping into those sections that are relevant to you, your stage and the challenges you face. You might also be interested to look at earlier or later chapters to cover things you might have missed on your scaling journey and to plan for what’s coming next.

The first half of the book is grouped around particular themes such as hiring, People processes and leadership. Within each of those chapters, you’ll find guidance appropriate to your stage of growth, for which headcount is a useful proxy. In the second half of the book, we shift to a focus on the challenges facing particular functional units, with dedicated chapters for each of the three organizational “engines” that you need to build: Technical, GTM and G&A, again broken down by headcount stage.

Alongside headcount, we use the following broader descriptions to refer to different phases of a startup’s journey:

- Early/initial phase—When you are starting out and iterating in order to achieve a minimum viable product (MVP), find product-market-fit (PMF, a product with highly engaged users), and then find go-to-market-fit (GTM-fit, a proven strategy for getting your product into customers’ hands). This usually happens between 0–125 headcount.

- High-growth—After achieving PMF and GTM-fit, your business is likely to experience a period of hyperscaling, at least doubling in headcount every year. This typically corresponds to 126–1,000 headcount.

- Pre-IPO—Having scaled the company, you’re preparing for a successful exit or the next phase of the journey as a larger corporation.

Throughout this book, you’ll encounter many phrases and terms of art related to startups, companies and hiring. Where it makes sense, we’ve explained and written these terms out in full at the first mention in the main text. Sometimes we’ll continue using the whole phrase to avoid an unattractive abbreviation, but sometimes elegance must fall at the hurdle of economy. Where the written out word or phrase is too long or cumbersome, we’ve used the abbreviation after the first mention. If there’s something you’re not sure about, you can always refer to the Glossary at the end of the book.

We hope you come back to this text many times over the course of your journey. At the very least, your time with the book should furnish you with fresh, validated frameworks for tackling critical people and organizational problems; a sense of the break points at which you need to change your approach; and a clear, actionable understanding of your evolving role as a founder.

Evolutions’ Revolutions

We tend to view evolution as slow but ceaseless change— the quintessential process of order emerging incrementally from randomness. Over millions of years, dinosaurs become doves and monkeys turn into humans. Yet the fossil record tells a different story, one of extended stasis disrupted by swift, dramatic transformation.

In the 1970s, the American paleontologists Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge dubbed this phenomenon “punctuated equilibrium”. It seems to take a major catastrophe—like an asteroid strike—to knock species out of their comfortable balance, and drive the rapid evolution of new traits, abilities and body types.

Climate change has catapulted us into a sixth great extinction. Evidence abounds that species are changing fast in the struggle to survive. The feathers of emperor penguins have become more yellow in the last 50 years to provide better camouflage as sea-ice melts and land is exposed, while galahs in Australia now have larger beaks, because drought makes opening seed pods more difficult.

What comes next? From what we know so far, the winners following periods of calamity tend to be the creative experimenters, testing novel adaptations to extreme conditions.

Stories of Chaos

The Lifecycle of startups

Changing landscapes, consistent challenges

It takes 10 years or more to take a company from idea to IPO—a span of time that encompasses an entire economic cycle. In other words, almost every successful venture-backed entrepreneur has to steer their company through both upturns and downturns in the economic cycle.

For founders getting started today, the focus is on achieving “more with less”, but the objective remains the same—to hire a tight and committed team that can create a product that customers love (PMF), and then find a way to sell it to them (GTM-fit)

Between 2000 and 2020, the time taken by highly successful venture-backed tech companies to scale to 500 headcount has shrunk for every stage of growth. While it used to take these companies more than eight years to get to the 500 headcount point, more recent successes took only five years.

Faster scaling offers benefits by locking out competitors and creating network effects more quickly. It reflects a more dynamic startup environment, with a greater availability of capital. Faster scaling is also the result of a deeper pool of experienced operators who have learned firsthand how to navigate high-growth, together with better software tools and cloud infrastructure to enable it.

Marketplaces tend towards a winnertakes-all modality, so they have to ramp quickly once they hit inflection. Consumer apps and D2C are rarely like this, so scaling needs to be more mindful of burn rate and contribution margin.

Damir Becirovic, Index Ventures

As companies start to see real productivity gains from AI, there will be a question for leaders around how to manage team size. If you have 10 × more productive engineers, do you cut back the team by 90%, or do you reinvest in R&D, taking advantage of these gains to go faster? In customer care, do you push to replace your entire team with AI chatbots, or do you ramp up your offer to VIP-grade treatment across the board? We expect to see different companies adopting different approaches to these decisions.

Dominic Jacquesson, Index Ventures

Higher interest rates have dampened the “blitzscaling” model of growth, while the bar for fundraising has risen in terms of demonstrable traction, user engagement and unit economics. However, companies that meet these criteria are still able to access the capital that fuels high-growth. Given that People (i. e. payroll) is the primary way in which capital is deployed in high-growth businesses, we believe that rapid scaling of teams will persist, albeit in a smaller cohort of the very best startups compared to what we witnessed in tech between 2015–19 when capital was cheap, and radically different from the boom years of 2020–21.

My message today to the very best outlier companies that have exceptional PMF and a distribution engine would be to scale aggressively. But this is very different to the broad majority of startups, who will have to keep expenditure and headcount tight.

Sofia Dolfe, Index Ventures

The other profound change we’ve seen since the Covid-19 pandemic has been the rise and normalization of remote and hybrid working. Companies have adopted very different practices, although there’s been a significant shift back to the office during 2022–24. At Index, we monitor open positions across our portfolio companies, including by location. Roles advertised as “remote” peaked at 32% during 2021, but dropped back to 21% by the end of 2023. Nonetheless, this is still dramatically above the 8% remote roles observed prior to the pandemic. The implications of remote and hybrid working on culture, recruiting, retention and performance are a significant and evolving topic of discussion and study that falls outside the scope of this handbook, but you will find excellent resources in our Further Reading section

The Big takeaways

Across all stages of growth, we have identified six thematic lessons relating to people, organization and leadership that you should keep in mind:

1 Keep your talent density high.

Making sure you have a concentration of truly excellent people from the start is a force-multiplier as you scale. The initial focus is on applying a high bar for hiring talent. As you scale, you need to complement this with strong performance management processes so you can nurture your stars and say farewell to those who hold you back.

3 Introduce people and organizational processes gradually.

It’s great to bring in some process early, but you should start simply. The philosophy is that “something is better than nothing,” and over time, processes can be enriched, personalized and optimized. This applies to many areas, including values, onboarding, training, internal comms, compensation, job leveling and an Objectives and Key Results framework (OKRs).

4 Adapt to your evolving role as a founder while you scale.

You start off as Chief Building Officer. You then become Chief Decision Officer, and ultimately, the Chief Inspiration Officer. Being conscious and accepting these shifts, as well as being deliberate in your transformation, will make you a better leader. At the same time, you need to recognize the special sauce that you bring to the company and not let it disappear—this is what will fulfill you as a leader.

5 Balance immediate with longer term priorities.

You need to be thoughtful about the downstream impact of people-related decisions that you might take today for the sake of expediency. Sometimes accepting the “debt” this incurs is the right thing to do. (For example, heavy early hiring in customer support, rather than focusing on automation.) But other times it is a big mistake. (For example, offering inflated job titles to close early hires.) You also need to cultivate a sense of judgment about when to invest in certain initiatives today that may offer compounding payback tomorrow, such as university recruiting.

6 Embrace change.

Change is the only constant in high-growth environments—changes in products, priorities, people, processes, systems and structures. You need to cultivate a resilient and trusting culture that accepts the need for change rather than resisting it, and where people collaborate to drive success. This is about accepting a measure of chaos and uncertainty at all stages of the journey, and achieving a temporary equilibrium that you need to be willing to throw away when necessary. You want to think of your company like a complex organism or natural system that survives by adaptation and evolution, not a machine that’s constructed to function only in one set of circumstances. This requires role modeling, transparency, consultation, empathy and over-communication. Bring people with you on the journey so they understand the “why” as well as the “what”.

Common early people mistakes

We’re an optimistic, future-focused team at Index. But of course we’ve seen our share of poor decision-making and observed how bad decisions taken early in a company’s journey can damage its prospects down the line. As in other complex systems, the initial conditions for a startup have an outsized effect on its later performance. Here are the “People” mistakes we see most frequently, which we advise you to avoid:

Insufficient focus on talent density

- Forming a founding team that lacks technical DNA

- Forgetting that no hire is better than a bad hire

- Being reluctant to get rid of A-holes or B-players

- Insufficiently focusing on diversity from the earliest stages

- Over-indexing on loyalty to the early team when you need to bring in more specialized or experienced talent

Mistakes around people and hiring processes

- Outsourcing early hiring rather than embracing founder-led recruiting

- Assuming others can make hiring decisions and stepping back too soon from personally vetting all candidates

- Not spotting when you need to hire an in-house recruiter

- Hiring an inexperienced in-house recruiter

- Inflating job titles, leading to resentment and attrition down the line

- Being seduced by sexy brands on a resume rather than focusing on competencies and fit

- Failing to establish and stick to compensation principles, seeing it as a win to hire cheaply, or conversely, by offering a sweetheart deal

- Insufficiently focusing on onboarding

Failing to future-proof and not investing upfront where it matters

- Being too slow to explicitly articulate the culture you want to build and the values that will underpin it

- Not communicating a clear vision, mission and strategy, allowing fiefdoms to develop, which undermine collaboration

- Building a tech stack for today’s scale and scope, which absorbs headcount and slows you down when you face tomorrow’s scale and scope

- Not recognizing when professional financial and legal advice really matter and are worth the expense

Hiring into the wrong roles

- Hiring a senior product leader too early, when the founder needs to personally own the product vision

- Hiring a senior salesperson too early rather than embracing founder-led sales

- Running key marketing and/or sales experiments through a generalist and therefore prematurely shutting down promising marketing and/or sales channels

Failing to hire into the right roles

- Not having a superstar owning early Community and Customer Support/ Experience (CX) functions, leading to an inadequate loop from early user feedback into product and growth

- Getting bogged down in operations by not hiring a Chief of Staff or Head of Business Operations (BizOps)

- Not recognizing when, and in which roles, you need to shift from generalists to specialists

- Reluctance to hire, or to properly partner with, an executive assistant (EA) as a way of creating leverage

Misallocating your time

- Spending too much time on low priority stuff for your stage (e.g. attending tech conferences, media appearances, meeting potential investors)

- Not investing in building and leveraging a full-stack network of advisors and mentors

- Not monitoring or creating space for the physical, mental and emotional well-being of your team and yourself

People challenges by headcount stage

Having a larger headcount is the inevitable consequence of building a successful business. You have a larger codebase to orchestrate, more customers to serve, more products to maintain and cross-sell, a higher volume of data to interpret, and more geographies to cover, among many other things.

Some questions and challenges will remain constant regardless of your size or stage, but mutate and evolve as you grow. For example:

- Is my hiring plan for the next twelve months appropriate and realistic?

- How can I keep my hiring bar high?

- Should I promote from within or bring in experienced talent from outside?

- How many direct reports should I have, and who should they be?

- Do I have too many, or too few, people in function X?

- What level of leadership do I need for function X? What are the differences?

- Is too much process slowing me down, or do I not have enough of it?

- How do I keep my team aligned around our key goals and milestones?

- What management reporting structure works best?

Other people and leadership challenges come into focus at more specific points as your headcount grows. We’ve therefore mapped out a framework for the steps you should be taking, and when you should be taking them, in relation to people and leadership. This is far from definitive, as every startup follows its own unique journey. Rather, the aim is to give you an idea of the sequence of challenges you’ll face and actions you’ll need to prioritize to address them. We’ll turn to every area listed here in greater detail throughout the book.

0

Coming together as a founding team (or choosing to be a solo founder) is the critical starting point to building a company. You’ll need to ensure that you collectively have sufficient “technical DNA” to be successful. You’ll also align as a founding team around a (scrappy) written statement that sets out the type of company you want to build. This includes the values, culture and behaviors you want to embody, as well as the company’s mission and vision—the impact you want to make on the world.

1–10

You’ll focus on creating your MVP and building out product features to move you towards initial PMF. You’ll be cash-strapped (pre-seed or seed only), so keep your team lean, with slow and limited additions to headcount. In pure software startups, hires will mostly be into technical roles. In Marketplace or Direct-to-Consumer (D2C) E-commerce startups, you’re likely to hire more broadly, including GTM and Operations roles. Hires will largely be drawn from the best of your own networks and your second-tier contacts. But you need to be thoughtful about diversity in this early team to avoid groupthink or a clone factory. Every team member will have super close working relationships with each other and with you, so internal comms will be fluid, with daily standups. Objectives are focused and known, but roles will be fuzzy, with the expectation that everyone will step in where needed. Though early, much of your company culture is also established during this stage, so take time to define what you want it to be.

11–50

With solid initial signs of PMF based on user acquisition and engagement, you can obtain significant funding (typically $5–20 million Series A) to support experiments towards developing a scalable GTM motion. With a timeline to hit growth and product milestones, you’ll step up to more systematic expansion of your team across a broader range of roles, including GTM and G&A. You might benefit from an internal recruiter to support outbound candidate sourcing and to embed a more systematic hiring process that keeps your bar high: engaging, screening, assessing, referencing and closing candidates. Your Technical team will split into squads. You’ll also appoint your first non-founder people managers, marking the beginning of hierarchy— with all its consequences, good and bad.

51–125

As you identify a successful GTM motion, you’ll build out a more specialist GTM team to scale it. Founders will step back from interviewing every hire as more managers and team members are approved for assessing excellence and values-fit. Retention will become a challenge alongside hiring, so you’ll need to roll out at least an initial performance management process plus basic manager training. With larger and more complex functional teams, you’ll hire two or three outside executives, potentially one each to lead Technical, GTM and G&A teams.

126–250

With a proven GTM fit established, you’ll rapidly scale GTM teams to take advantage of it, which potentially includes regional or international teams. Above 150 people—a point known as The Dunbar Number—nobody can really know everyone else at the company. People processes will instead need to get more sophisticated, especially when it comes to high potential talent (HiPo’s), compensation bands and internal comms. You’ll need to define your Employer Value Proposition (EVP) and communicate it as part of your talent brand to drive hiring and retention. You might also experiment with internships and graduate hiring. This is often a crunch phase for CEOs as complexity ramps up but you lack a proven executive bench. Appoint and/or substitute an additional two to three executives, probably including a VP People. You may also need your first “Scaler” exec, as opposed to the “Builders” you’ve been working with up until now. That is, experienced “managers of managers” for your larger teams, most likely in engineering or sales. You’ll establish an executive committee and senior management team to formalize and clarify decision-making. Your budgeting and planning processes will become more robust, combining top-down and bottom-up inputs.

251–500

As the company’s reach expands across multiple geographies and/or products, matrix management structures will be needed. (This is where individuals report to more than one boss.) People processes will extend to include career progression frameworks and ongoing people analytics. Human resources business partners (HRBPs) will be appointed to support functional leadership. You’ll appoint an additional two to three executive roles, establishing a solid executive bench. This will probably include a Chief People Officer. This is also the most likely phase where you will see a shift from a co-founding CTO to an outside engineering leader. You’ll need to establish a remuneration committee (Remco) as a subcommittee of your mainboard to monitor and approve decisions around compensation, succession and talent management.

501–1,000

With continued expansion across geographies and new product and revenue lines, you’ll embark on a deeper focus on unit economics and automation. This entails paying down the “debt” built up during earlier growth phases, when you overhired to get critical stuff done. Automation will go hand-in-hand with periodic reorganizations across different parts of the business to optimize efficiency and effectiveness. As you prepare internally for a potential IPO, you’ll need robust and documented processes related to financial, legal, commercial and people aspects of the business.

You’ll have a solid People and Talent team in place, with People processes following a regular rhythm. You’ll introduce systems and processes for talent pipelining, career development, internal mobility, graduate recruitment and succession planning.

Internal promotion will overtake external hiring as your primary means of filling senior individual contributor (IC) and first-line manager roles.

Your high-growth company will now be ready for an IPO. It will still feel like a rollercoaster ride on the inside, but you’ll feel a deep sense of parental pride. You will have brought something extraordinary and unique into the world, nurturing its development into a confident and healthy “teenager” ready to make its mark on the wider world!

Plastic fantastic

The brain’s extraordinary adaptability, known as neuroplasticity, is greatest when we’re young. Based on feedback and self-organization, the brain’s architecture continually rewires itself based on our environment and what we’re learning about it. During certain developmental windows, neural networks form new connections while pruning away weak ones. A child more easily picks up languages or rebounds after trauma compared to an adult, thanks to this enhanced capacity to flex and change.

However, plasticity and learning ability tend to decline with age. Neurons become less dynamic and connections ossify. It becomes harder to acquire skills or recover from brain injuries.

Yet emerging research suggests we can combat this loss by staying socially, physically and cognitively active. Both athletic and mental fitness turn out to be “use it or lose it” abilities. Regular exercise, learning new things, finding meaningful work and maintaining close ties to communities and loved ones all preserve neuroplasticity. Consequently, these factors build cognitive resilience and executive function while lowering the risks of strokes and dementia. Embracing change and striving for purpose, it seems, are antidotes to calcification.

Stories of Chaos

Foundations of Success

Founding Team

As soon as you’ve identified a critical customer need and hit upon an innovative solution to address it, you’ll face your first people-related challenge. Who do you want by your side as you build out your product and company?

Your “founding DNA” has a huge influence on what your short-term priorities should be, as well as having long-term implications for your team and company. Who is on the initial founding team will determine:

- Values and culture

- Hiring priorities and sequence

- Network hiring potential

Choose whether to fly solo or find co-founders

The majority of highly successful startups (71% in our research) have two or three founders. Multiple co-founders aren’t essential, and there are several high-profile counterexamples involving solo entrepreneurs (12% in our research). Nonetheless, most successful founders embrace the belief that they couldn’t have gone it alone.

I had already had a successful exit, and was happy working at Microsoft after the acquisition of my first company, Adallom. I’m thankful that I had great co-founders to push me and give me the confidence to try again.

Assaf Rappaport, CEO & Co-Founder of Wiz

Exceptions that prove the rule: successful solo founders

Amazon Jeff Bezos

SpaceX Elon Musk

Bumble Whitney Wolfe Herd

Craigslist Craig Newmark

Spanx Sara Blakely

Bolt Markus Villig

If you’re building a Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) or Business-to-Consumer (B2C) App business, a pair of founders makes sense as CEO and CTO. For Marketplaces, you might want a third co-founder to focus on operational complexity or to bring specialized industry expertise. For D2C E-commerce, the span of skills extends even further to include marketing and supply chain management. It can be tough to assemble such a broad co-founding team from the outset, so you might choose to go it alone at the start and build the right mix of talent further down the road.

The reality of how founding teams come together is extremely varied. Besides having studied together (e.g. Google), worked together (e.g. Plaid), or grown up together (e.g. Discord), cofounders can be introduced by mutual connections, or even be siblings (e.g. Patrick and John Collison at Stripe). There can also be a fuzzy period as a co-founder finds themselves drawn more deeply into a project before they commit fully. But we find that co-founders almost always join before a company’s first fundraising event (93% of the time). If you’re in the position of actively searching for a co-founder, three significant factors to bear in mind are:

- Whether at least one of you is “technical”

- The balance of experience between you

- Diversity, since including people with a range of perspectives and life experiences is more likely to future-proof your company

My co-founder is one of the most experienced and highly regarded tech leaders in France. Meanwhile, I bring energy, freshness and optimism. Between us, it’s not 2+2=4, but 2+2=10!

Eléonore Crespo, Co-CEO & Co-Founder, Pigment

The equity split between co-founders may or may not be equal, reflecting these varied routes, timings and backgrounds.

Bake in technical founding DNA

At Index Ventures (and pretty much all VCs), we have a strong preference for founding teams that score highly on technical DNA. This might be obvious in the case of pure software companies such as SaaS and B2C Apps, but it also extends to other business models.

Why? Without technical DNA in your founding team, you’ll need to outsource product development to either freelancers or an agency. This will slow down your development of an MVP, as well as the iteration cycle to move you towards PMF. More technically adept competitors pursuing the same problem will be at an advantage. Even if you manage to achieve traction, at some point, you’ll need to bring development in-house. This will create further delays as you hire a Technical Lead and team, figure out how to incentivize them, hope you haven’t made hiring errors, and allow them to get to grips with an unfamiliar codebase.

The value of technical co-founders is backed up by our data. The majority of successful companies (78%) had either a founding CTO or a technical CEO (i. e. having a technical degree or work experience in a technical role). This pattern is apparent across business models, even in D2C E-commerce (56%).

Given the increasing importance of design and growing sophistication of consumers, we are also seeing more technical founders with specific product design experience.

We’re seeing a lot more designers nowadays as co-founders, and even as CEOs. Several generational companies now serve as role models: Linear, Notion, Pinterest, Canva and of course, Airbnb. It’s no longer a case of pure tech or business profiles as founders.

Soleio, Designer × Investor, Dropbox and Facebook (former)

Understand the impact of your prior experience

Many studies have attempted to profile what successful entrepreneurs look like. These illustrate clear trends in terms of age (more than half are 25–35 years old) and university pedigree (almost half attended a global Top Twenty institution). However, at Index we believe that great entrepreneurs can come from anywhere, can be anyone, and can “discover their mission” at any point in their career.

Exceptional entrepreneurs can be younger or older, first-time or repeat. Young university dropouts can be a special persona, with insane maturity. Their insight and confidence can be mind-blowing—usually underpinned by one simple insight, but which is derived from original firstprinciples thinking. On the other hand, repeat entrepreneurs can have exceptional clarity about the customer problem they are solving, the type of company they want to build, and the talent they need to bring it to fruition.

Martin Mignot, Index Ventures

Whatever your background, you need to be self-aware about your gaps and tendencies, and work to fix or complement them. A key difference that influences your optimal route to achieving entrepreneurial success is between:

Less experienced founders

- Younger, first-time founders, with limited operating experience

- Examples: Dylan Field at Figma; Patrick and John Collison at Stripe; Evan Spiegel at Snap

More experienced founders

- Older, repeat founders, with deeper operating experience

- Examples: Jason Citron at Discord; Assaf Rappaport at Wiz

Hybrid founders

- Either younger, but already repeat founders, with directly relevant operating experience, or a founding team which combines more and less experienced founders

- Examples: Melanie Perkins at Canva; Whitney Wolfe Herd at Bumble

Less experienced founders usually need to work harder to secure senior early Technical hires, while more experienced founders benefit from hiring a couple of more junior profiles for the sake of leverage and diversity.

These founding team profiles can lead to very different cultures. If you’re less experienced and young, you’ll generally have less appeal to (and may have an implicit bias against hiring) older individuals. If you’re older and more experienced, you could face the opposite challenge. Experienced ex-operator founders also have a propensity to build in too much process and infrastructure early on, because they’re familiar with how big companies do things—for example, leveling frameworks and HR systems that are unnecessary at an early stage. On the other hand, more experienced founders are more likely to personally know your targeted early hires—often highly experienced individuals you’ve previously worked with, where mutual trust is high. But your network may be narrow and more homogeneous, with a risk of limiting diversity and creating a monoculture.

Younger founders need to focus on building their network to bring in senior points of view, which includes advisors as well as hires. Older founders can offer mentorship to junior hires, whilst younger founders can offer experienced hires the space to expand and to put their insights into practice.

Adam Ward, Founding Partner, Growth by Design Talent

Did being a repeat founder contribute to our success? Yeah! My first startup was my business school of hard knocks, and I got paid for the privilege.

Jason Citron, CEO & Co-Founder, Discord

Either way, you need to break out of these mental boxes soon. The key is to play to your strengths, but also work at breaking out of the limitations of your background. See Chapter 4 for more detail on making the right early senior hires.

Values, culture and diversity

Define your culture

Every founder has a unique attitude and approach to work based on a blend of personality and personal and professional history. Many founders are conscious of their leadership style when they start their company and have a sense of the type of organization that they want to build. They might make this explicit from day one, with a set of written principles to guide the journey, or it might remain implicit for a while. Either way, it will manifest in every behavior, decision and hire, and will become the bedrock of your company’s values and culture.

While you need to personally role model values through your own decisions and behavior, the sooner you can articulate your values in written form, the better. This is something you can iterate and evolve over time. But by defining and operationalizing your values explicitly, it allows the team, and particularly team managers, to become “culture-carriers”—encouraging or discouraging particular behaviors, providing feedback when there’s a mismatch, and ensuring incentives are aligned with values. Later on, these behaviors can be illustrated through examples within specific teams, such as Engineering, Sales or CX.

Everyone says you should write down your values early on. But I didn’t really understand this until I ran my first startup without having done this work, and witnessed the consequences on hiring and on culture. Then I got it. You have to be really intentional about your culture. From day one.

Jason Citron, CEO & Co-Founder, Discord

Our early culture was very R&D-centric, but we’re now evolving to put customers at the core. For example, we used to have a value of ‘Aim high, build to last.’ It’s now shifted to ‘Commit to excellence’.

Lindsay Grenawalt, Chief People Officer, Cockroach Labs

By articulating your values, they can manifest in your culture and be embedded into each one of your People processes as you scale:

- Hiring for values-fit and training interviewers on how to do this

- Onboarding and management training to reinforce values and behaviors

- Continuous feedback and performance management to catch people doing things right (or wrong), to course-correct, and to weed out A-holes

- Rewards frameworks that reflect and reinforce values alignment

- Internal comms to celebrate examples of values being put into practice, and to monitor perceptions of how reality aligns with the values

In a company, values are to culture what DNA is to human personality. Values provide a code, which is manifested in a unique and quirky way as companies grow up and interact with the world. Founders are the parents who provide the company’s DNA, and who nurture its employees to enable it to thrive.

Dominic Jacquesson, Index Ventures

Values at Maven

My dad is an entrepreneur, and he advised me to codify values early on. We’ve refreshed them every couple of years since. Initially they were theoretical and principles-based, but as we’ve grown, they’ve become operationalized, grounded in the experience of what we want versus don’t want.

Some have stood the test of time:

- “Walk through walls.” Healthcare innovation is hard, so we’ve constantly had to move mountains to make things happen—negotiating with major health plans and compressing timeframes, as well as evaluating how our frontline teams are supporting patients every single day.

- “Keep healthcare human.” We’ve always been skeptical that bots can replace doctors. We recognized the importance of human contact early on, and we’ve stuck with this belief.

Other values have evolved to become more specific:

- “Be humble and curious” has shifted to “Continuously learn, including about yourself.” This orients to a more actionable growth mindset.

- “Customer obsession” is now “Embrace the service mindset.” This keeps it relevant for internal as well as external teams.

And we’ve added a new one:

- “Lead with data.” In the early days, we didn’t have as much data, and now that we do, it increasingly drives our alignment as we scale.

We continuously reinforce our values too:

- Monday all-hands include a section on wins to highlight the values that we leveraged to achieve success

- Slack channel to nominate team members for our Annual Values Awards, one per team

- Values-focused interviews for all candidates, with a recruiter spearheading our efforts to systematize and optimize how we conduct them

- Two “State of the Union” speeches I give each year, which always include a section on our values

- Posters all over the office showcasing them

Kate Ryder, CEO & Founder

There’s no secret recipe for what your company’s values should be. In fact, trying to cut and paste values from a textbook is a recipe for failure. The critical ingredient is authenticity. You can have a successful culture which is centered on high performance or one that is centered on collaborativeness. What’s important is that the reality of your culture—how decisions are actually made and which behaviors are rewarded—is aligned with what you claim your values are.

There’s no such thing as a perfect culture—that’s called a cult.

Didier Elzinga, CEO & Co-Founder, Culture Amp

This isn’t to deny the existence of toxic cultures, or even “authentically toxic” cultures—places that follow principles sincerely which nonetheless lead to a negative work environment for many people. Overarching ethical, inclusive and legal guardrails are fundamental requirements for any legitimate company.

However, people differ in the type of organization they want to work for. Some thrive in competitive environments, others in fully in-person ones, and yet others prefer conditions of ambiguity. If articulated and expressed clearly, your values should act as signals and filters for the types of individuals that you attract, hire and retain in your company.

Values should involve trade-offs rather than being mere platitudes that everyone would agree with. ‘Move fast and break things’ is distinct from ‘Strive for excellence’.

Sofia Dolfe, Index Ventures

Culture is to recruiting what product is to marketing. A great product attracts customers, while a great culture attracts more talented people.

Hubspot’s Culture Code

Examples of clearly articulated values

1. Patreon—Core behaviors

We don’t like the term “cultural fit” at Patreon. We look for “culture add” and “core behavior fit”. We hire people who bring new experiences, backgrounds and perspectives to the table. At the same time, we make it clear that you must demonstrate these behaviors to succeed at Patreon:

- Put creators first

- Be an energy giver

- Be candid, always

- Move fast as hell

- Seek learning

- Respect your teammates’ time

- Just fix it

From 2018, when Patreon had 100–200 employees.

2. Netflix—Extract from Culture Deck

Our high performance culture is not right for everyone

- Many people love our culture, and stay a long time.

| They thrive on excellence and candor and change.

| They would be disappointed if given a severance package but would retain lots of mutual warmth and respect.- Some people, however, value job security and stability over performance, and don’t like our culture.

| They feel fearful at Netflix.

| They are sometimes bitter if let go, and feel that we are a political place to work.- We’re getting better at attracting only the former and helping the latter realize that we are not right for them.

As the founder, you should revisit your values every year or two, involving a wider group of leaders and trusted culture-carriers so that it becomes more collaborative. You might leave them unchanged, but you might also find it appropriate to add, delete or modify values. And with each iteration as you scale, you should push the envelope further in applying your values to every People process, articulating them into celebrated behaviors relevant for each function, and actively communicating them to your larger and more dispersed team.

No principle is too holy to slay.

Harsh Sinha, CTO, Wise

I’ve interviewed thousands of people, and I have a hidden agenda—I’m studying companies. I’ll ask, ‘How would you rate working at Company X on a scale of one to five?’ If they give a five, I’ll dig in, looking for insights that accumulate into a point of view on each major company’s culture, like what do employees value from each of them, and what patterns drive success? This informs how I steer our culture as we grow. I want our leavers to be praising Gong down the line!

Amit Bendov, CEO & Co-Founder, Gong

Make diversity a priority

From the outset, you need to challenge and interrogate yourself about what “excellence” looks like so as to mitigate against bias. The diversity this creates will ensure that your business stays flexible and resilient over a longer period of time. While diversity is increasingly in the public awareness, doing diversity right is hard.

From day one, we made a conscious decision to prioritize gender diversity within our Technical team. Where many startups might put diversity on the backburner, labeling it ‘something to fix later,’ I was very deliberate about pushing hard for diverse candidate pools from the start. Referrals were a challenge, and I held back some hiring from my own network to ensure we retained a more gender balanced early team. We put a lot of time and effort into writing and speaking publicly, resulting in some amazing and very visible role models and representation externally. This in turn helped improve our EVP and we had many people mention team diversity as a reason for applying. It’s not something you can ever really stop working on, but putting in the effort early makes it self-reinforcing.

Pete Hamilton, CTO & Co-Founder, incident.io

To me, diversity doesn’t only come down to what we typically think of: age, gender, ethnic background. It’s much more than that, including the persona of the people you bring on board. For example, if I’m great at engineering operations, it’s possible that I’ll be drawn to like-minded engineering candidates because I can simply recognize and relate to them much more easily. But I need different personas on my team—the creative kinds, the architects, the fast movers, plus of course the operationally minded kinds. Having this balance, this diversity, allows me to build a stronger team. Broadening your lens in this way can and will extend to other protected characteristics. This attitude towards diversity, by focusing on as many dimensions as possible, rallies the whole company rather than being potentially alienating to a subset we leave out. It helps avoid an ‘us versus them’ mindset, and constantly adds to the dimensions of diversity you are being mindful of.

Farnaz Azmoodeh, CTO, Linktree and VP Engineering (former), Snap

As a founder, you might need to be willing to take a bigger risk on diverse candidates. The talent pool is likely to be narrower and it’s naive to think that there are no trade-offs involved in building a more diverse workforce. In the short-term, it might even be the case that you can scale and ship faster simply by picking proven winners.

Going after a diverse workforce may well incur a short-term cost. Hiring velocity could slow down and you’ll have to go to extra efforts to attract and identify diverse candidates. The one thing you should never do is lower your talent bar in the pursuit of diversity. It backfires and people see through it. Instead, focus your early efforts on a small number of diverse hires closer to leadership level. They will really attract diverse talent further down, allowing you to scale up.

Farnaz Azmoodeh, CTO, Linktree and VP Engineering (former), Snap

Lots of founders are tempted into the shortcut of hiring a bunch of folks similar to themselves. So they may end up with a load of math geniuses, but basically no cultural diversity. You pay for this approach down the line in so many ways. You need diversity—across age, gender, ethnicity, backgrounds and experiences—from really early.

Danny Rimer, Index Ventures

Challenge your assumptions

We analyzed the tenures of early engineering hires into highly successful startups based on where they had worked before. The conventional wisdom is that candidates with prior startup experience are more likely to cope with the ambiguity and fast pace of working in a young and ambitious company. What we found runs counter to this assumption—engineers who previously worked at venturebacked companies actually had a shorter tenure than those who hadn’t.

Prior experience in a venture-backed tech company?

Average tenure (months)

No 42

Yes 37NB: Prior experience in a company that was originally venture-backed but is now exited (e.g. Meta) is classified as “no”.

The lesson is that when you start hiring, focus on competencies and character, and not on where candidates have worked before.

Here are some practical tips about how to embed diversity in your team:

- Interviews are often unstructured in the early stages of building your business. This risks introducing bias, as you’ll inevitably bring your own lens to the discussion and might end up hiring people like you. Instead, we advise using a competency-based interview framework to make sure everyone gets a fair hearing. This shifts the focus away from experience and grades or brands on a resume (which diverse candidates might not bring) to figuring out how candidates achieved their goals. (See Chapter 4 for more detail.)

- Alongside competency, the individuals who thrive in startups exhibit hunger, passion and grit. These are characteristics that you’re just as likely, if not more so, to find in diverse candidates. By ensuring that you assess for and put equal weight on these qualities, you will develop a fairer hiring process.

- Every time you solicit names of potential candidates, pause and ask if referrers can think of any great diverse candidates you should speak to. Directing your network to think more broadly will yield a wider range of profiles.

- Frontload your outreach efforts with diverse candidates, and be persistent. Building relationships will take time. If you spend the first couple weeks of each hiring process consciously targeting a more diverse set of candidates, you will build stronger pipelines.

- For some roles, finding a balanced or diverse group of candidates can be very tricky. We advise you to map your overall organization and levels of roles you will want to hire over the next 12 (or even more) months, and consciously target your efforts to build out a diverse pipeline for your future needs.

- Monitor conversion rates at the offer stage in particular. Many companies are getting better at pipelining diverse candidates, only to find systemic bias kick in at the final offer stage. The tendency can be to extend offers to the “best” candidate, falling back on biased norms.

- Use tools such as Textio to ensure that the language of your job advertisements isn’t putting off the people you are trying to reach. For example, using combative or military metaphors can cause applicants to skew male. That includes checking your outreach message, job descriptions and interview questions.

- If you don’t yet have any diversity in your team, draw in your investors or board to help in the hiring and interviewing process.

Define your vision, mission and strategy

Vision and mission are foundational elements in your journey as a founder. While values and culture define the type of company you want to build, the mission and vision set out the impact that you want to make on the world.

There are multiple perspectives on the meaning of a company’s vision and mission. What follows is our point of view at Index, though the time frames can be adapted, and the two terms can even be switched around.

Vision: This is the purpose or raison d’être of your company, expressing the change you want to create in the world. It’s what you exist to achieve over a 10 to 20-year timeframe, and is your “North Star” to help you decide what you should, and should not, prioritize.

- Microsoft—“Empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more”

- Nike—“Bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world”

- Figma—“Make design accessible to all”

- Roblox—“Build a human co-experience platform that enables billions of users to come together to play, learn, communicate, explore and expand their friendships”

Mission: This is an internal statement of what the company aims to achieve over a three to five year horizon. It should be both ambitious and measurable, allowing employees to link their individual contributions to top-level company goals. For example, “Be a top three global CRM leader with $5 billion revenues.”

Strategy: This is a very specific and quantified plan with a three-year timeline. It’s a set of actions that will take you closer towards fulfilling your vision and mission. It can be segmented into annual (and then quarterly) objectives that guide planning, prioritization, investment, budgeting and goal setting.

Having a purity of purpose expressed through your mission allows you to shape even your commercial targets in reference to their positive impact, rather than becoming mercenary and cynical. For example, “When we win, good things happen’ and ‘Move fast because better healthcare can’t wait!

Kate Ryder, CEO & Founder, Maven

As you scale, your public vision and mission won’t remain the same. Success will enable you to widen your horizons and become more ambitious. When your company is still young and small, a grand vision can come across as somewhat absurd and confusing, especially when stated on a signup page or job description. There’s only one group of individuals who are really interested in hearing your shoot-for-the-sky ambitions right from the start—VCs. But recognize that what you say in an investment pitch isn’t going to be the same as what you say in a sales meeting with your first, or even your hundredth, customer.

Our mission has evolved. It started out focused on women’s health, reflecting our early services around pregnancy and postpartum. This naturally led us to address related issues including miscarriage, infertility and family building support for same-sex couples. Over time, our patients wanted support around pediatric health and encompassing support for dads, such as sleep coaches. Our mission now covers women’s and family health, but I stood firm with retaining our focus on women. Menopause support is now our fastest selling product.

Kate Ryder, CEO & Founder, Maven

More than meets the eye

Before internet memes, in the 1990s there was Magic Eye: books featuring hallucinatory 3D images floating above kaleidoscopic colorscapes, only visible once you relax your focus. The series was a runaway “viral” success, selling more than 40 million copies worldwide.

These optical illusions known as “autostereograms” date back hundreds of years, but enjoyed an unlikely revival after the 1970s, thanks to the Hungarian-American neuroscientist Béla Julesz. While working at Bell Labs on the problem of how to recognize camouflaged objects in pictures taken by spy planes, he realized that two patterns of random dots could create the illusion of depth.

His finding showed the workings of “stereopsis” or depth perception, caused by images landing on slightly different locations on a person’s retinas. Dimensionality, it turned out, didn’t even require a recognizable image. Instead, the brain was capable of matching hundreds of near-copies within an apparently chaotic repeating pattern, creating the experience of depth for the viewer.

In the 1990s, new computer algorithms catalyzed an explosion of autostereogram art. Today, modern digital techniques can translate nearly any 3D form into an illusion complete with photorealistic details and thousands of layers. Beneath the chaos, it’s always worth looking for quietly recurring principles—only visible when one peers deeper, more slowly, and a bit aslant.

Stories of Chaos

Hiring people

Start with founder-led recruiting

Make the most of your network

Your network as a founding team has a major influence on who and how you hire. If you previously worked at a tech or high-growth company, you might know exactly which engineers or designers or marketers you’d like to work with. Hiring from your network makes hiring decisions less risky, and can give you strong conviction to compensate these individuals sufficiently to pull them in.

The downside of this approach is that you might create a team lacking in diversity, or without the “zero to one” skills you need to get something off the ground. It also doesn’t expand the envelope of your future referral network, and can create an “us versus them” mentality when you bring in anyone outside of your own circle. Having a mix of genders, backgrounds, experience and networks really helps. See our section in Chapter 3 for concrete advice about how to improve diversity within your business and offset the risk of a monoculture when hiring from within your network.

I used to be wary of hiring friends, but I did it loads, and whilst I have lost one or two, it ultimately worked out very well.

Matt Schulman, CEO & Founder, Pave

Hires from your personal network are primarily choosing you and your mission. But you also need to think about their three to five year career aspirations to know how to sell your opportunity to them. How will it take them closer to their goals?

Our first 10 hires all came from our direct network or from our second-degree network. We couldn’t offer them safety, but we could offer them impact, and they were all already working either at startups or as freelancers, so they knew and accepted the risk.

Job van der Voort, CEO & Co-Founder, Remote

Hiring from network—incident.io

All three of our co-founders had strong networks. I personally had a list of about 10 folks I thought were truly excellent, and who had said to me over the years, “If you ever start a business, let me know.” Half of these were unavailable when we started, having moved or started their own businesses. But it was natural for me to tap the other half. We were very open about our position, saying, “We have no funding currently and no master business plan, but if we did have the money to pay you, would you be interested?” Two people immediately put their hands up, which was a huge vote of confidence. I was asking them to give up cushy jobs, so I did a lot of anti-selling actually. I didn’t want to sugarcoat the challenge ahead or let them down if things didn’t work out. We all knew each other, having worked before at the same company, so I was very conscious of the potential culture trap. But honestly, the advantage of my early team being people I could trust out of the box definitely outweighed the risks.

As an early stage founder, I’d encourage others to do the same. Your job isn’t just to mitigate risks, but rather to move fast and to maximize upside for the business. We offered them a lot of equity to make up for substantial pay cuts, and they accepted once we had a term sheet, even before we had the funds in the bank. Overall, for our early team, we aimed for 50% founder network, 25% secondary network, and 25% non-network, which mostly came from inbound candidates.

Pete Hamilton, CTO & Co-Founder

Winning means securing the talent to write better code. Your competitors aren’t just companies tackling a similar problem space to you. They also include every startup, bank and big tech company that is competing for top engineers. So if you know great people, grab them.

Simon Lambert, CTO, Birdie

Expect half your early hires to have experience in tech companies

When we analyzed startup hiring trends, we saw that the proportion of early startup hires with previous tech and VC-backed company experience has risen over time. That tracks the wider growth of tech ecosystems in the Bay Area and beyond. Individuals with these backgrounds are more likely to be comfortable with the ambiguity and fast-paced change that you need to accept in a startup. Our projections for the next generation of successful startups suggest that you should aim for 50–60% of early hires to have experience working for VC-backed tech companies.

Be your own recruiter

Few startups hire an in-house recruiter ahead of raising a Series A, and only 10% of the companies we analyzed had hired a recruiter by the time their headcount hit 10. You’re unlikely to be making many hires, and you’re trying to preserve capital. Hiring a recruiter might make sense if you’re a solo founder, given your lack of bandwidth. But you and your co-founders always need to learn how to pitch your company effectively before you can hope to teach someone else.

Founders often underestimate the amount of time they will spend recruiting. Especially as a solo founder. You’re endlessly sourcing, pitching and assessing candidates, with no-one to share the load with.

Zabie Elmgren, Index Ventures

There were days when I’d spend six hours in a small, insulated phone booth, doing interviews from 7 am. ‘Pete’s booth’ be came a bit of a running joke on the team. I only wish I had installed a fan!

Pete Hamilton, CTO & Co-Founder, incident.io

Using recruitment agencies can be helpful to broaden your lens, but be careful who you work with, and don’t rely on them to solve your hiring challenges.

The biggest reason that outside recruiters succeed (or not) has to do with the clarity of the briefing from the founder. If you’re an experienced founder, you can probably do this better.

Adam Ward, Founding Partner, Growth by Design Talent

I spent loads of time and money on agencies and contractors. It felt like a silver bullet, and they sounded so convincing. But it utterly failed. They didn’t internalize our value proposition and couldn’t sell us when we were still a nobody. Only you can do it in the very early days.

Matt Schulman, CEO & Founder, Pave

The takeaway is that you have to be personally proactive in identifying, and engaging with, potential candidates. This founder-led recruiting strategy involves a mix between:

- Secondary network—“friends of friends” including angels, investors and other people you know and trust

- Cold outbound—searching for specific profiles from specific companies on LinkedIn (you are advised to become proficient at using LinkedIn Boolean search), and then reaching out directly

- Inbound—cultivating an inbound flow of interested candidates through social media, blog posts, media presence, etc

Our first tranche of hires were split between our direct network and our secondary network (particularly via angel investors), plus a few intentionally sourced from outside our network, to keep diversity of thinking and backgrounds and to avoid any cliques developing.

Eléonore Crespo, Co-CEO & Co-Founder, Pigment

When asking for referrals, be as specific as possible. Having a job description can help with this, and being concrete makes it easier for people to think about relevant profiles. Assess how well the referrer knows the candidate whom they are introducing, how confident their recommendation is, and also how high their standards are.

If you identify candidates who are connected to your network, ask for an intro rather than reaching out cold. This gives you a much greater chance of engaging them, as does using email versus InMail on LinkedIn (which few engineers check regularly). When pitching candidates, sell your experience and your mission, and also mention any high-profile angels or VCs that are backing you.

When you’re leveraging referrals to build a candidate pipeline, apply a scoring approach. Ask three questions: How well do you know them, how recently, and for how long? Weigh these to generate a signal strength score. Also ask how they’d rate the individual as a percentile of all people they’ve worked with.

Adam Ward, Founding Partner, Growth by Design Talent

When you reach out cold to potential candidates, they will probably look you up and assess whether you’re credible and worth talking to. So ensure you look the part. Your own LinkedIn profile (personal and company) needs to sparkle. Make the most of any high-profile angel investors or advisors that are already supporting you. If you’re technical, your GitHub commits should be complete and up-to-date.

When founders reach out cold to talent, the common mistake is to make it about themselves. Wrong! Make it about the other person—‘I saw your commits, that you did X, that you know Y.’ Link what the person has done to what you have, or to what you’re trying to do. Say that you’d love to connect with them around this shared interest rather than just, ‘Let’s have a coffee.’ Or even worse, ‘Are you looking for a job?’ The initial challenge is simply engagement.

Adam Ward, Founding Partner, Growth by Design Talent

I’d never hired anyone before I founded Maven and couldn’t rely on my own network. I looked for people from companies with cultures of excellence, including a tough boss. This was more important for me than the sector. You have to take risks with early hires, and I had to hustle for every single one. But they all came with values that were aligned, so it worked well.

Kate Ryder, CEO & Founder, Maven

You need to be thinking about the hires you’ll need in six months, not just the immediate future. Particularly for roles outside your comfort zone, you want to meet candidates as soon as possible to help you calibrate the standard you should be aiming for, followed by building a pipeline of potential candidates.

Set a goal for yourself—‘I will have two conversations a week for pipeline roles that I need in the next phase’.

Bryan Offutt, Index Ventures

Pave—Top three founder-led hiring tips

1. Leverage your broader network.

“Every single night, I’d spend one or two hours sourcing on LinkedIn. I went through all my first and seconddegree connections, asking each of them for three talent intros. It was incessant, but as a result, almost all my hires were made through my wider network, despite having only worked for two years prior.”2. Embrace your imposter syndrome.

“Yes I’m young, but I’d just state this upfront and then focus on what I could offer. I don’t believe in puffing yourself up—good talent will see through it.”3. Power-referencing.

“To close candidates, I used what I call a ‘Preemptive 360.’ I’d take multiple references, and on every call, I’d ask, ‘If I have the chance to work with X, what’s the best way of ensuring their success?’ I’d dig in, and take copious notes. I’d then package this into detailed feedback on my offer call, including how we can put it into effect when they join. It blows candidates away, and I’ve had a 100% close rate using this approach.”Matt Schulman, CEO & Founder

Inbound recruitment is closely tied to your overall brand strength, and is rarely a significant source of hires at this very early stage. The same thing applies to university recruiting. We’ll discuss both in more detail in the next section on build ing your recruiting engine.

Look at your overall team composition

Analyzing the hiring patterns of successful startups offers templates for how to approach teambuilding, which vary by business model.

On average, 4.5 of the first 10 hires are in technical roles, with 3 in GTM, and the remaining 2.5 split across G&A and Operations.

The best SaaS and B2C Apps startups focus more on technical roles, representing over half of their first 10 hires. By contrast, early hires in Marketplaces, especially in D2C companies, skew more heavily to Operations. Hiring into G&A roles is consistent across the four business models.

It makes sense to have more Technical hires in SaaS and B2C Apps, given the software orientation of these companies. Marketplaces and D2C need Operations hires early, reflecting the need to spin-up supply chains or to manage supply and demand dynamics.

TeamPlan—Explore our entire library of 210 highly-successful startups for more detailed insights into team structure, experience profiles, and hiring plans at this 0–10 headcount phase, and beyond.