Rewarding Talent

The Founder’s

Guide to Stock Options

The Index Ventures experience

Our insight

The untapped potential of employee stock options

At Index Ventures, we’re proud to back the most ambitious entrepreneurs, and support them on their journey to realize their vision.

We were born in Europe more than 20 years ago, and today we have feet firmly planted on both sides of the Atlantic. From our hubs in London and San Francisco, we use our deep knowledge to invest in outstanding startups. We have 160 companies in our portfolio, equally split between Europe and the US.

World-changing tech companies can start anywhere – but we recognise Silicon Valley’s sophisticated model of scaling and investing in startups as second to none. We adapt and apply best practices from Silicon Valley to our startups in Europe, to prime them for success.

One of the key ingredients is employee ownership. In Silicon Valley, employee stock option grants have helped attract the world’s best talent to small startups with limited cash, but near limitless potential. The result is that these startups have the people they need to succeed early on.

In Europe, employee ownership is less common – and there has been no clear playbook for startups to follow. This is exacerbated by the complexities of doing business on a continent made up of 30 different countries, all with different cultural norms, regulations, tax incentives, and so on.

This handbook is designed to help European founders make critical decisions. Who do you offer stock options to? How many? When? How do you adapt your policy as you grow, and as you move into different geographies? How can you ensure employees understand the scheme?

We’ve included the basic information you need to design your stock option plan and policies, ready-to-use allocation models, and advice from those who’ve been through it – plus our own perspective as investors. You’ll also find case studies from Index portfolio companies throughout the book, demonstrating the range of best practice. Founders and executives from the likes of Farfetch and Elastic share their approaches to employee ownership, their successes and their mistakes, and the valuable lessons they’ve learned in the process.

We chose to open-source our work, so you can read or download the entire Rewarding Talent handbook from our website at: www.indexventures.com/rewarding-talent

Alongside this handbook, we’ve developed the OptionPlan tool, which will help you determine option allocations for your entire team, whether you’re at seed stage or Series A.

You can also find it on our website at: www.indexventures.com/optionplan

Our take

Bringing employee ownership to Europe

At Index, we believe that a fresh approach to employee ownership is key to creating European tech giants on the scale of Google or Amazon. Until then, too much of Europe’s top talent will simply join the European arms of US firms, relocate, or stick to lower-risk corporate jobs.

In the US, option grants are driven by intense competition for talent. There are established benchmarks for option grants to employees at all stages and levels. Thousands of employees across hundreds of startups have benefited financially following company exits. Many have been inspired to become founders or angel investors themselves, creating a virtuous cycle of innovation and startup activity.

Europe has seen fewer exits, and option grant benchmarks haven’t been available, so founders have been forced to make up their own rules. But competition for talent is heating up, and with more high- profile exits, individuals are more willing to exchange cash for stock options, especially in major tech hubs.

We therefore expect the next generation of European startups to offer options more widely to employees. By staying ahead of this trend, startups can attract and retain the best talent out there. However, this must be coupled with changes in national policies, which encourage the use of stock options across the continent.

The methodology

How we put this handbook together

This handbook is based on what we believe is the most extensive research ever conducted on employee stock options in European startups, which included:

-

Cap table analysis by funding round across 73 companies in the Index European portfolio

-

Analysis of over 4,000 individual option grants from more than 200 startups across Europe and the US, supported by Option Impact from Advanced HR

-

In-depth interviews with founders, CFOs and executives of 27 Index-backed European companies from seed stage to post-IPO

-

Survey on ESOP practices completed by executives from 53 European startups and former startups, representing over 11,000 total employees

-

Review of regulatory and tax policy in the US and key European and global markets, supported by Taylor Wessing, Wilson Sonsini, and several other law firms

Introduction to this edition

There was a tremendous response from the European startup ecosystem when the original Rewarding Talent handbook and OptionPlan app were released in December 2017. One year on, it has become the ‘playbook’ for European entrepreneurs. We are now delighted to release this updated and expanded edition.

Recognising that startups need to hire and motivate top talent right from the outset, we have expanded our research and recommendations to cover equity allocations for seed companies. We have also added a new case study from Elastic. Guidance on topics including retention grants and strategic advisors has been enriched.

You will also find guidance on stock option practice and policies for twelve additional countries, within Europe and beyond.

Finally, we are making specific recommendations for policymakers. We see their role as crucial in helping to create a regulatory environment which fosters entrepreneurship and innovation.

If you have feedback, please reach out to Dominic Jacquesson at talent@indexventures.com

Key findings

A top-level summary

We found big differences in employee ownership between the US and Europe. They are presented throughout this book, but here are a few key points.

-

European employees own less of the startups they work for than US employees.

For late-stage companies, they own around 10%, versus 20% in the US.

-

Employee ownership levels vary much more in Europe than the US.

In Europe, employee ownership in late-stage startups ranges from 4% to 20%. In the US, ownership is more consistent, as stock option allocation is driven by market forces.

-

Ownership rules adopted by startups vary between Europe and the US.

For example, provisions for leavers, and accelerated vesting following a change in control.

-

In Europe, stock options are executive-biased.

Two-thirds of stock options are allocated to executives, and one third to employees below executive level. In the US, it’s the reverse.

-

European employees still don’t expect stock options much of the time.

US employees joining a tech startup with fewer than 100 staff will expect stock options straight away. This is much less true in Europe, although expectations are steadily rising.

-

European founders haven’t known how to allocate stock options across their team.

Benchmarks are available in the US, guiding founders to make compelling grants. These haven’t been available in Europe, where founders have been ‘flying blind’.

-

European option holders are often disadvantaged.

In much of Europe, employees need to pay a high strike price, and they will be taxed heavily upon exercise as well as sale. Leavers often get nothing.

-

There is wide variation in national policy across Europe, with Estonia, the UK, and France most supportive of employee ownership.

Regulations and tax frameworks are radically different across Europe. Estonia has the most favourable approach of any country reviewed globally. The UK’s EMI scheme and French BSPCE’s are both better than what is available in the US. Other countries, including Germany, lag behind.

-

Employee ownership correlates to how deeply technical a startup is.

An AI or enterprise software startup requires more technical know-how than a straightforward e-commerce startup. These employees are at a premium in today’s economies, and more likely to seek stock options.

-

Salary differences between startups and established companies are narrowing.

Startups still pay lower cash salaries, but competition for talent is forcing them to narrow the gap. Stock options are ever more important to hire and retain top talent.

At Index, we are focused on helping founders to address these challenges. There has already been a noticeable change in approach since we launched this handbook in December 2017.

We will continue to argue for progressive, pro-innovation thinking from investors and policymakers across the whole of Europe.

Stock options 101

A top-level summary

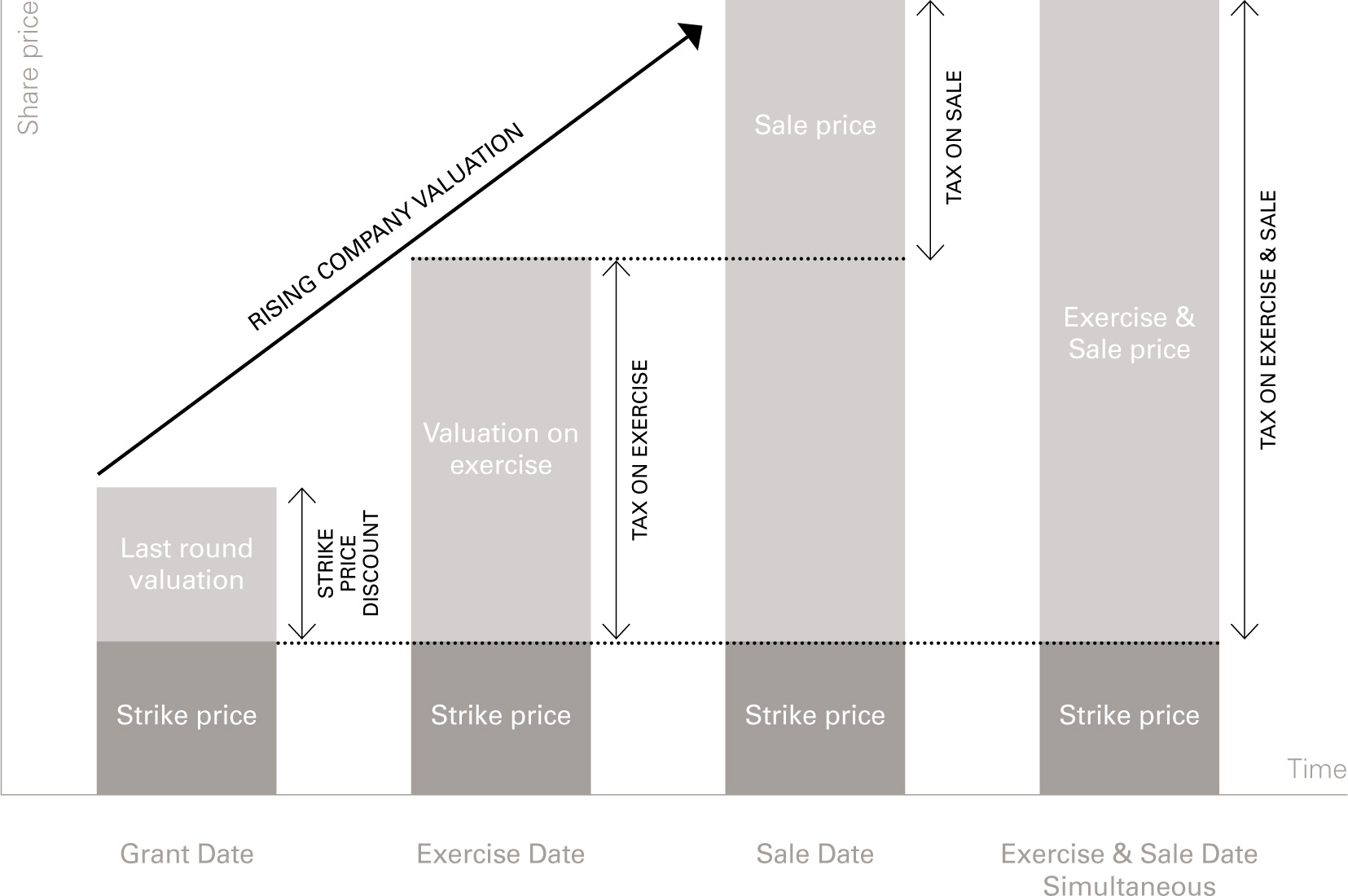

Options are a special type of contract. They grant the holder the right – but not the obligation – to buy or sell an asset at a set price, on or before a certain date.

In established US practice, stock options grant the holder the right to buy shares (exercise their options) at a set (or strike) price, within a ten-year period.

The option allows the owner to buy a certain number of shares. The right to exercise will vest over a four-year period; typically, there will be a one-year cliff before the holder has any rights, then vesting will be linear, allowing the holder to buy a further 25% of their shares at the end of years one, two, three and four.

If they want to exercise their options, the holder must pay the exercise price (strike price x number of options). In return they will receive ordinary shares in the company. The holder may be able to sell these shares immediately, or retain them in the hope that they will further appreciate in value.

It only makes sense to exercise options if the current share price of the company exceeds the strike price. Exercise requires a cash payment, so the decision to exercise also depends on how long the holder thinks they will have to wait before they can see a cash return by selling the shares. Any tax incurred will also influence this decision.

Stock options are the instrument of choice for employee ownership in US startups. They are better than giving shares to an employee because there is no premium or tax to pay upfront, making them risk-free for both employee and company.

In Europe, the rules and tax treatment of stock options varies widely between countries. In some countries, it still makes sense to use stock options. In others, alternative instruments are used instead. But in each case the purpose remains the same – to incentivise employees, by rewarding them if the company’s value increases.

To keep things simple, we’ve referred to all of these instruments as ‘stock options’ in this handbook, even though their legal status may be very different. These include warrants, Restricted Stock Units (RSU), and virtual stock options.

You’ll find a detailed glossary of legal and financial terminology in the Appendix.

Employee ownership

Employee ownership:

Why it matters

As a founder, the equity in your company is your most precious asset. You should be unwilling to give it up lightly. But you also need to leverage it wisely, in order to access the two things that are essential for success – financial capital, and human capital.

Ambitious founders know that talent is their key bottleneck, and that building a world class company requires a world class team. In a competitive talent market, where FAANGs, BATs, banks, and corporates can offer high salaries and generous benefits for top candidates (especially in technical roles), it can be daunting to compete.

However, as a startup, you have two big advantages. Crucially, you can offer a compelling culture and mission. Your employees can feel part of a close- knit team, directly involved in shaping something truly innovative, rather than feeling like cogs in a machine.

But you can also offer a more tangible benefit. Ownership, in the form of stock options. Giving your team the opportunity to own a stake in a company that could become highly valuable a few years down the line, and to participate in the financial upside that could result, is a compelling proposition.

With less cash at your disposal for salaries, especially in the early days, stock options are also given to employees in lieu of the cash compensation and benefits that they might receive at larger companies. This enables smart founders to secure the best talent available.

In fact, offering stock options can benefit founders in several ways.

Hiring

Helping you secure the best talent, even when you’re up against companies with much deeper pockets.

Retention

Once you’ve hired top talent, you need to hold onto it. Stock options vest over multiple years, appreciate in line with your valuation, can be topped-up, and create disincentives for leaving. This gives your employees ongoing reasons to stick with you.

Motivation

Having a personal stake in the success of the company encourages employees to work harder and be more ambitious.

Alignment

Stock options direct all employees towards the same goal – the company’s overall, long-term success. They act as an incentive for collaboration.

Using equity wisely

Diluting your equity is only worthwhile if it truly allows you to hire, retain, motivate and align the very best talent.

If your stock option program is perceived as unfair, inconsistent, unreal, or is simply not understood, cynicism can set in. You will have given up your most precious asset, without obtaining the benefits. It is critical that your employees understand what stock options are, and perceive their grants as contractually protected, and objectively and fairly awarded across the team.

This is the driver behind much of the advice in this book: adopting a formula-driven system for awards, strengthening rights for leavers, and being more open with your employees. More traditional European lawyers and advisors often propose approaches and grants which are biased in favour of the employer, but we invite you to be more enlightened. In our experience, rewarding talent meaningfully and fairly is not only warm and fuzzy, it also makes business sense.

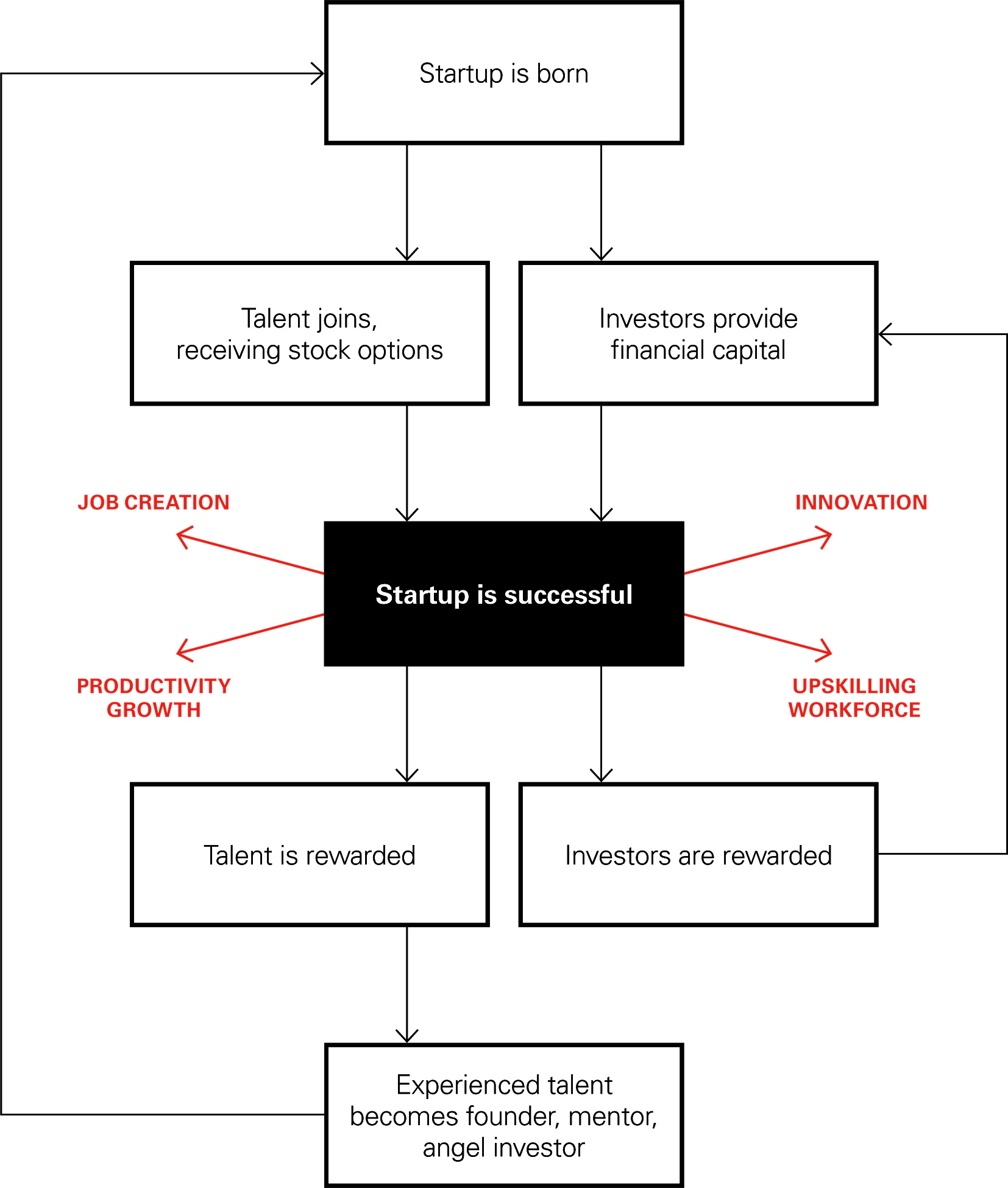

The Silicon Valley flywheel

Employee ownership pulls in top talent

Employee ownership has been at the core of Silicon Valley thinking for over 30 years. The story of the part-time masseuse who joined Google in its infancy, and ended up a millionaire, has now been played out thousands of times, in all sorts of startups. This has drawn thousands more talented employees into the startup ecosystem.

Employees from successful startups often go on to start their own companies, or invest in the next generation of startups as angels. A cycle of entrepreneurship is fostered.

Employee stock options are standard practice in Silicon Valley and across the US, where grants are driven by the market. Widely available benchmark data helps founders determine grants for any given role at each startup stage.

In contrast, levels of adoption vary across Europe. Grants here are mainly determined by the founder’s philosophy: the culture they want to create, and how mission-driven they want to be. A lower risk-appetite on the part of talent, and onerous regulations and taxation, feed into an environment where employee ownership is low..

Ambitious founders should think and act globally from day one. This starts with a forward-thinking, consistent approach to employee ownership. Sharing the pie with employees – in other words, offering them equity – is a great way to grow the size of the pie over time.

Staying ahead of the curve

A message to European founders

In much of Europe, it is still possible to get a startup off the ground without giving your team stock options.

But expectations are rising, particularly in major tech hubs such as London, due to the growing number of big exits of VC-backed startups. Employees are more likely to know others who have benefited from stock options, and want to ‘get in on the action’. If you offer options proactively, you can hook in the very best people and access talent that you would not otherwise have been able to reach.

At least as importantly, stock options are a way of retaining talent as you scale. In a few years’ time, if you continue to scale and raise brand awareness, your team’s success will make them hot targets for other companies looking to poach. If you have not built in sufficient upside and retention options, individuals crucial to your success are likely to be tempted by better offers elsewhere.

It is our view that the next generation of successful European startups will not achieve greatness if they do not effectively reward talent through the use of stock options.

Criteo – Bringing Silicon Valley practices to Europe

Founded in Paris: 2006

No. Employees: 2,800

Index initial investment: Seed round, 2007

Offices: France, US, UK, Spain, India, Turkey, Sweden, Russia, Germany, Singapore, Korea, Brazil, Japan

Criteo is the global leader in digital performance display advertising, partnering with over 3,000 international advertisers to deliver highly-targeted campaigns.

The best of both worlds

Criteo was founded in France, and retains a Paris headquarters and R&D centre, but the US is its largest market. In 2013, seven years after it was founded, it listed on NASDAQ (CRTO).

Jean-Baptiste Rudelle, co-founder and CEO, viewed Criteo’s dual locations as an opportunity.

We’ve implemented best practices from both markets. The combination makes our company stronger.

Learning from the US

At the beginning, Criteo did not offer stock options to employees. At the time, employee ownership was rare in France and candidates were not concerned with equity.

Interview candidates in Paris asked us about meal tickets, not about share options.

Things changed when Criteo expanded into the US and Jean-Baptiste realized immediately that the company would have to adopt US standards.

Our second hire, an Office Manager asked about share options during her job interview. This would never have happened in France, but Silicon Valley was very different.

The Silicon Valley attitude is: we’re asking people to go on an adventure with us. If we find treasure, everyone deserves a piece. You can see the logic.

As a result, Criteo decided to offer equity to everyone in the US, regardless of role or seniority. A few years later, they expanded the policy, offering stock options to all employees, regardless of geography. Jean-Baptiste Rudelle, saw the benefits in aligning and motivating his team once he implemented the new policy.

When I see the cohesion and enthusiasm stock options have generated, I’m very glad we embraced the idea.

Finding the treasure

When Criteo floated on NASDAQ in September 2013, at least 50 employees became millionaires overnight. Jean- Baptiste recalls one particular employee, who joined as a part-time intern and worked his way up.

He took a risk and it paid off. I’m grateful to everyone who was part of our journey.

Startup ownership

Founders, investors and employees

A startup’s success depends on three groups of people: founders, investors, and employees.

You – the founder or co-founder – are the visionary, and the final decision-maker.

Investors place their faith in you and your vision, contributing capital to kickstart and scale your business, and offering advice and expertise along the way.

Your startup is only as great as the people building it – your employees. It’s a big risk to join an unproven business like yours, especially when well-established companies offer similar, more assured positions. Employees are your most valuable asset, and you need to treat them accordingly.

Together, these three groups determine the fate of your company. Company ownership is a great way to recognise and reward everyone’s commitment.

Cap tables

Your cap table breaks down your company’s ownership. It lists all the shareholders, and the number, class, and percentage of shares each holds.

Founders and investors are the main shareholders. This includes early investors, such as friends, family and business angels, and later investors, such as venture capital funds. If you issue stock options to employees, you’ll have an ESOP on your cap table, representing the total option pool available.

All too often, we’ve seen founders make regrettable decisions during early capital raises: giving away too much equity too soon, or on unfavourable terms. These mistakes can unnecessarily dilute your stake in the company and make it difficult to attract further funding.

How ownership evolves over time

From one to many

Funding rounds are a useful proxy for the stage and scale of a startup, as it moves from seed to Series A, Series B and beyond. However, there is a lot of variation between startups at each stage. For the purpose of having a shared understanding, the table below sets out some typical characteristics of Index- funded European startups at each stage:

| Funding Rounds | Pre-seed | Seed | Series A | Series B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of investor | Self-funded, friends and family | Angel investors (individuals/syndicate), seed-stage and micro funds | VC investors | VC investors, potentially growth or strategic investors |

| Typical round | <$500k | $1m ($0.5–2m) | $5m ($3–20m) | $20m ($10–40m) |

| Pre-money valuation | Not applicable | $5m ($3–8m) | $25m ($20 – 60m) | $100m ($50–150m) |

| Development phase | Ideation, beta-testing, MVP launch | MVP and initial signs of traction | Commercially viable product, testing, go-to- market strategies | Ramp up, go-to-market, internationalise |

| Typical headcount growth | Founders only, with non-employee contributors | From 0 to 10 | From 10 to 60 | From 60 to 150 |

| Hires made | Not applicable in most cases | Initial team

|

Ramp up

|

Build-out

|

On day one, you (and your fellow co-founders) will own 100% of your company’s shares. As you raise capital from third party investors, you’ll issue additional shares. And as you hire employees (or advisors), you may offer them stock options. Stock option holders are not shareholders.

They appear on a separate line on the cap table (in your ESOP). The total number of issued shares and outstanding stock options in your ESOP is known collectively as your fully diluted equity (FDE).

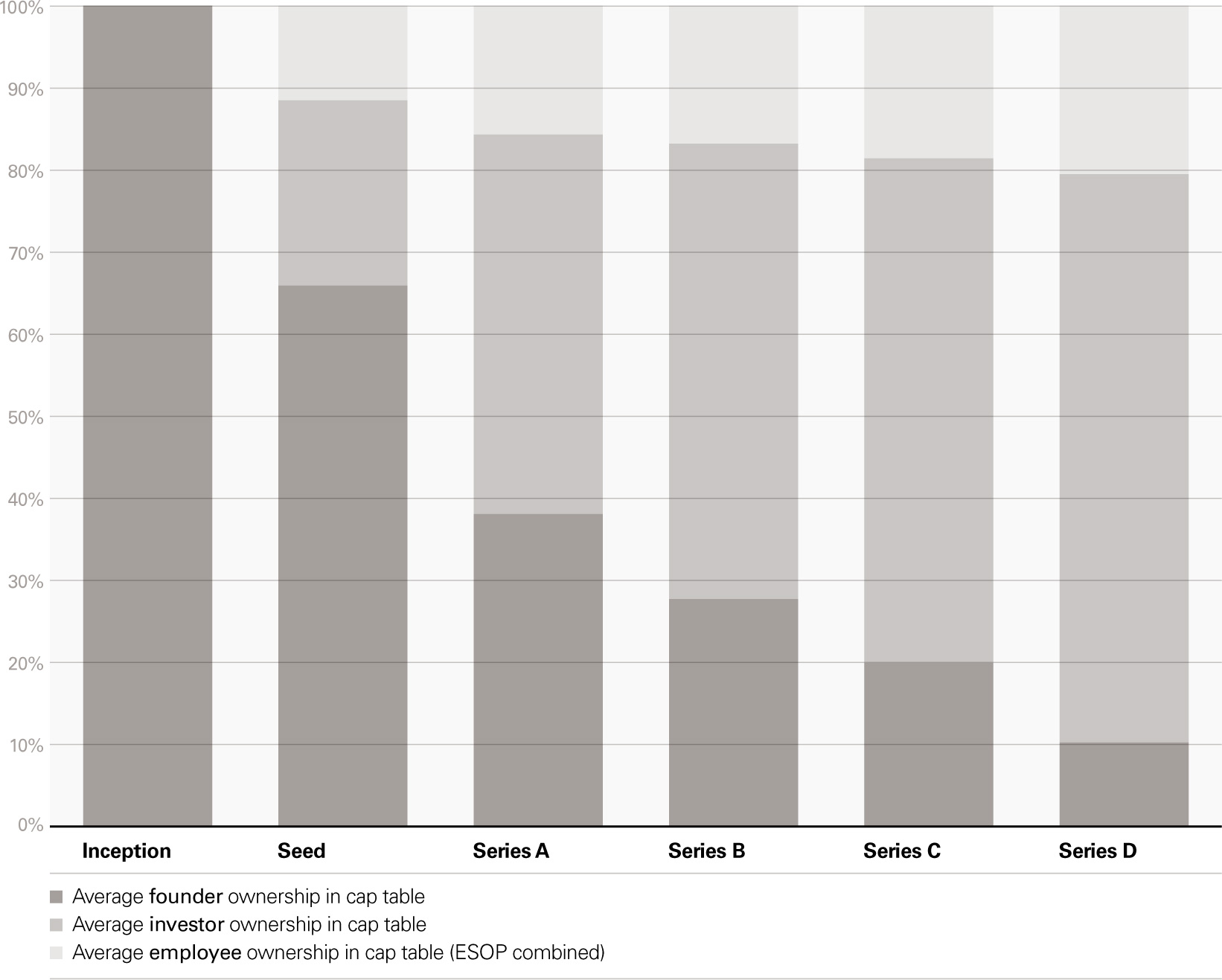

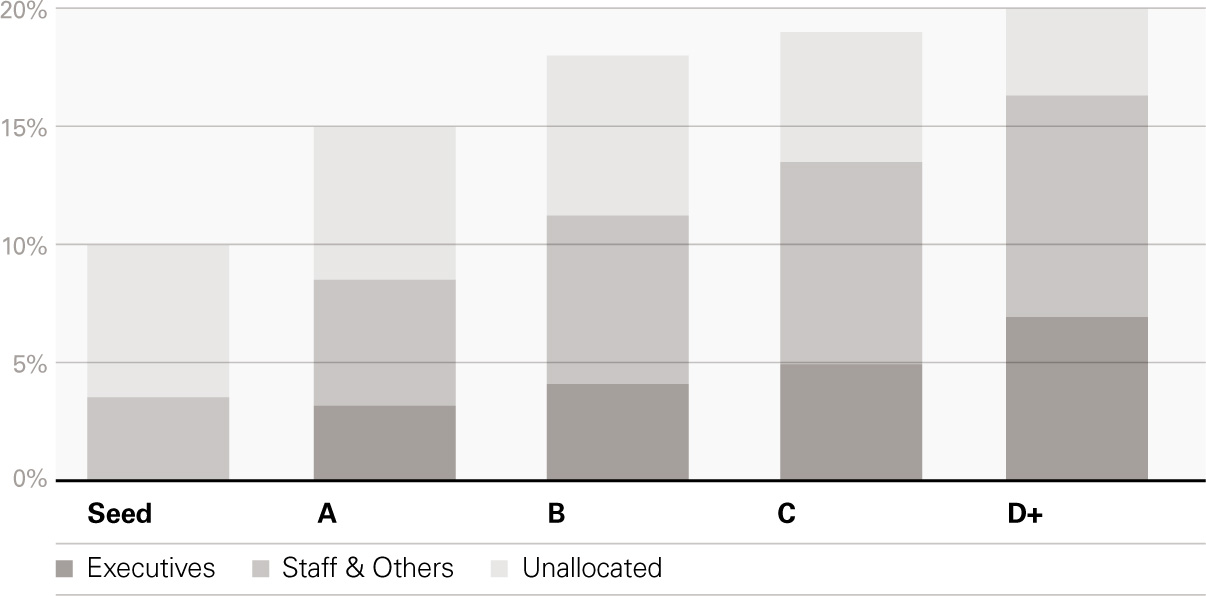

Evolution of ownership in US startups across funding rounds

(where Founding CEO remains in place)

The impact of dilution

When you raise additional capital, pre-existing shareholders are diluted. This dilution is proportional to the amount of capital raised, and inversely proportional to the company valuation you achieve. Any options granted to an employee at any point in time are diluted in the same way.

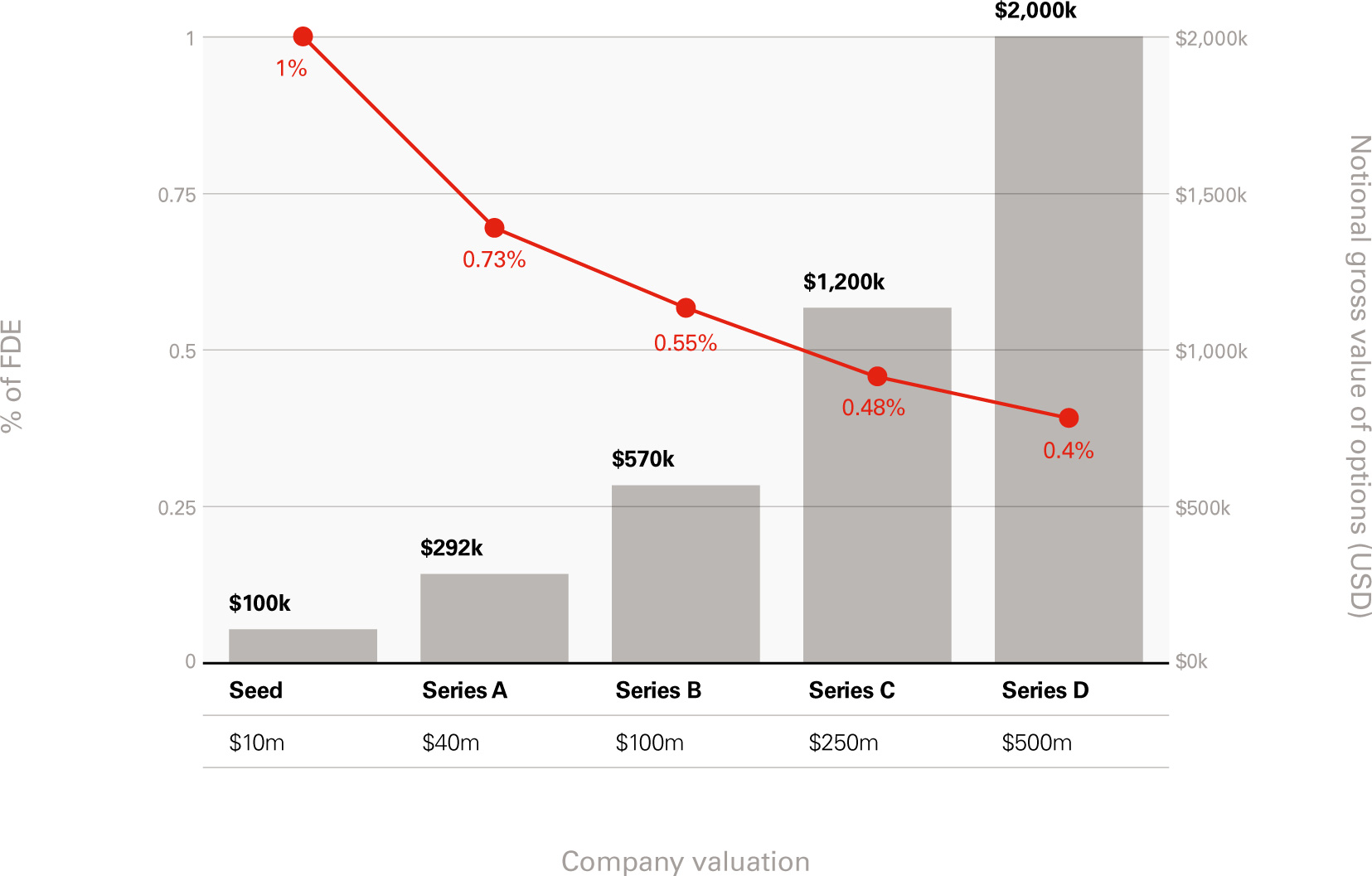

This level of dilution might appear unattractive to an employee granted options early on. But it doesn’t take account of valuation increases as the company scales up and attracts further funding. In other words, an early employee’s options will convert into a smaller percentage of the company, but may still be worth more in dollar terms. The table below shows the impact of dilution on a seed-stage hire, initially granted options over 1% of the company’s FDE. It also shows the notional gross value of these options, for a strongly-performing startup as it scales.

Typical employee option dilution over multiple funding rounds

An employee owning 1% of the company’s FDE in common shares at a notional gross value of $100,000, will own only 0.40% of the company at Series D, as a result of dilution. However, the value of this diluted stake might be as high as $2 million. This shows how valuable stock options can be.

Common and preference shareholders

There are two main share classes:

-

Common (or ordinary): owned by founders, employees, and seed investors

-

Preference (or prefs): usually owned by institutional investors.

Stock options, when exercised, become common stock. If the company is sold at a lower valuation than the preferred shareholders paid for it, they will be the first to get their money back. Generally, anything left after repaying the liquidation preferences will be distributed among common shareholders. Later stage companies may have multiple layers of prefs at multiple valuation points. There are also more complex ways of structuring prefs. If the exit valuation for the company is lower than one or more of the previous investment rounds, option holders (and other holders of common stock) will only receive proceeds, if at all, after the pref holders have been paid back.

ESOP size

How much should employees own?

How much of your company’s FDE should you set aside for your ESOP? If you already have an ESOP component in your cap table, should you top it up?

You’ll need to answer these questions as part of each fundraise.

ESOP size is a board-level decision. Given the legal and administrative overheads, you won’t want to revisit it between rounds of funding. So the size of your ESOP should aim to cover all your potential talent needs through to your next round.

You’ll need to tread a careful balance. You want to make sure your ESOP allocation is sufficient, but if you over- allocate, you risk diluting your stake, and your existing investors’ stake.

The table below shows an indicative example illustrating the impact of ESOP size on shareholder dilution at Series A, whether at 10%, 15% or 20%.

| Pre SeriesA | PostA – 10% ESOP | PostA – 15% ESOP | PostA – 20% ESOP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Founders | 65% | 47% | 43% | 40% |

| Existing investors | 25% | 18% | 17% | 15% |

| New investors | 0% | 25% | 25% | 25% |

| ESOP – existing | 10% | 7% | 7% | 6% |

| ESOP – top up | – | 3% | 8% | 14% |

| ESOP – total | 10% | 10% | 15% | 20% |

| Total ownership | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

In theory, you should base your ESOP allocation on your hiring plan through to your next fundraising. However, sticking to a plan for 12 – 18 months in the future might feel over-ambitious.

In any case, unexpected opportunities or challenges are bound to impact your hiring plan. Your company might grow quicker than expected. Or, you might meet an executive with huge potential to transform the business, who expects a substantial option grant.

In practice, most founders take a top- down approach, and VC investors will expect your ESOP to be sized at a round figure.

ESOP size at seed

Traditionally, ESOPs are set to 10% at seed. This is the recommendation of Seedcamp, and still the norm in both Europe and the US. However, some accelerators, including Y Combinator and The Family, now advocate 20%. They recommend that seed investors should increase their valuation of the company to accommodate the larger ESOP.

This doesn’t mean you should allocate or promise all of this amount to your early employees. But it recognises the importance of stock options for securing top talent when company cash is particularly constrained.

The composition of the founding team can also influence what is the right ESOP size. For example, if you are:

-

A solo founder who needs multiple key hires

-

Co-founding team thinking of outsourcing early development versus hiring engineers

-

Lacking a technical co-founder, and need to hire a non-founding CTO

If your focus is on leading-edge technical challenges (such as Internet of Things hardware) or deep tech (such as virtual reality or AI deep learning), you’ll need a large and exceptional technical team.

Competition for such talent is fierce. And you’ll be contending with the deepest pockets around – including Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple. These hires will expect high offers of equity participation, so you’ll be likely to need a larger ESOP than average.

ESOP size at Series A and beyond

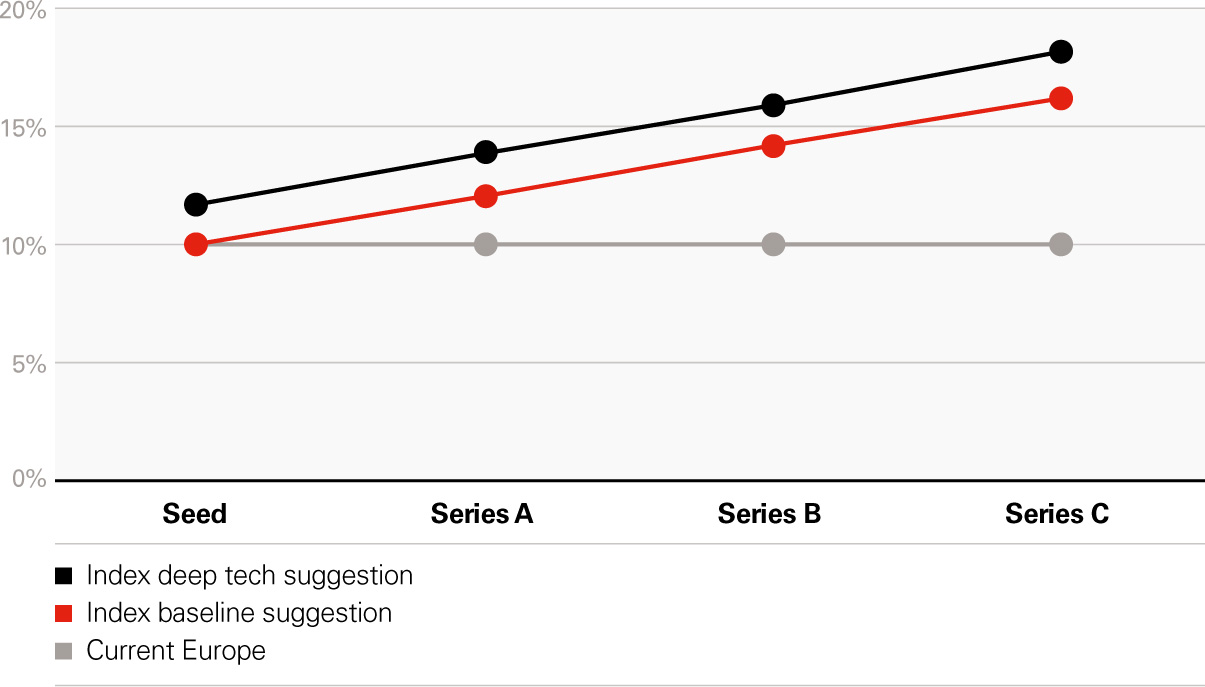

In the US, ESOPs are typically increased from 10% at seed to 15% at Series A. The ESOP then grows with each funding round – reaching 20%, or even 25%, by Series D. The ESOP is topped up to provide more firepower, as more employees are hired and leadership teams are put in place. This pattern is illustrated in the company ownership graph earlier in this chapter.

In Europe, whilst seed ESOPs are also usually set at 10%, our research indicates that, on average, this figure doesn’t rise with successive funding rounds. Instead, the ESOP ‘flat lines’. It gets topped back up to 10% at each stage, after accounting for the dilution of existing option holders. We also found a much wider range than in the US, with ownership between 4% and 20% by Series D. But this means that on average, European employees end up with only half as much ownership in later stages, compared to their US counterparts.

We believe this difference is a key issue in the European startup ecosystem which needs to be addressed. We identify four key reasons behind it:

-

Government policy

-

Risk appetite – of talent

-

Mindset – of entrepreneurs and investors

-

Lack of benchmarks

Our aim at Index is to address each of these factors, increasing employee ownership in Europe through the research and recommendations in this handbook.

We can also validate ESOP size bottom-up. We’ve set out a plausible scenario for your Series A hiring plan and individual allocations in the OptionPlan app that accompanies this handbook. We also apply this scenario in chapter 6. If you were to follow this scenario entirely, you’d need a 12% ESOP to cover your needs up to your Series B fundraise.

It is extremely unlikely that your company’s situation will exactly match our default scenario. So we recommend using our OptionPlan app to customise your own option plan, and to more accurately gauge the size of ESOP you need. However, it is very likely to fall within the range of 10 –15%.

We have also modelled ESOP size requirements beyond Series A, into Series B and Series C. This combines the OptionPlan benchmarks for grant sizes with our experience of hiring trajectories. It projects an average ESOP size for the next generation of successful European startups set at 12% for Series A, rising to 14% for Series B and 16% for Series C.

Projected ESOP size in the next generation of successful European startups

Source: Index Ventures analysis

Source: Index Ventures analysis

We have already discussed how ESOP size can be affected by the composition of your founding team, and how deeply technical your company is. But there are two other significant factors in Europe to consider.

Your philosophy

What kind of company culture do you want to create? How mission-driven will you be?

You might mirror a Silicon Valley mindset, using equity to win and retain the best talent, and encourage alignment across your team. To offer options to all employees, including large options to attract exceptional individuals from major companies, you’ll need a substantial ESOP.

If you’re more concerned about dilution, you can consider offering higher cash compensation to employees instead. You might also hire less experienced individuals you believe will grow into their roles, as they’ll be less likely to expect large stock option grants.

Where you are

Generally, the size of a company’s ESOP is closely linked to the maturity of the local ecosystem. In regions that haven’t seen many high-profile successful exits, people are less aware of – or perhaps more sceptical about – the potential value of stock options. Whereas thriving local ecosystems create more competition for talent, which means startups must offer larger grants to secure the best people.

Unsurprisingly, London – Europe’s largest startup hub – has the highest expectations overall in Europe. Across the rest of the continent, there’s a very mixed picture. In some places, legal and tax rules also affect the attractiveness of options. (See chapter 7)

We expect these dynamics to shift over time, but the direction of travel is clearly towards rising employee expectations in all geographies.

As the ecosystem matures, employees get more sophisticated, and are more willing to trade-off salary for options.

Martin Mignot

Partner, Index Ventures

ESOP rules

You will have carved out space on your cap table for your ESOP as part of your seed fundraising. However, you cannot make any stock option grants until you have legally created your ESOP plan, and chosen the rules governing how it operates.

In the US, ESOP plans will typically be formalised after a seed round, and sometimes even earlier. There are generally accepted guidelines to follow and the legal costs are low. Startups would also find it challenging to make any hires without being able to formalise stock option grants immediately.

In Europe, the costs of setting up a plan are often higher, and early hires can usually be secured on the basis of informal promises of stock options. So it is common to see ESOP plans formalised following Series A fundraising.

Your board will need to approve your ESOP rules. It’s important to make them as clear and consistent as possible, so you can avoid changing them or creating exceptions later on. This chapter covers the major rules, particularly where there are significant differences in practice between Europe and the US.

Vesting schedules

Consider a back-loaded vesting schedule

If stock options could be converted into shares immediately, they wouldn’t be effective for retaining employees. A vesting schedule allows employees to accumulate their stake in the company and exercise more options over time.

If an employee leaves the company before they are fully vested, they will retain rights over their vested portion. The unvested portion is cancelled and returns to the unallocated ESOP pool.

The cliff

Typically, no options are vested during the first year (called the ‘cliff’). This gives companies time to weed out mis-hires without suffering dilution.

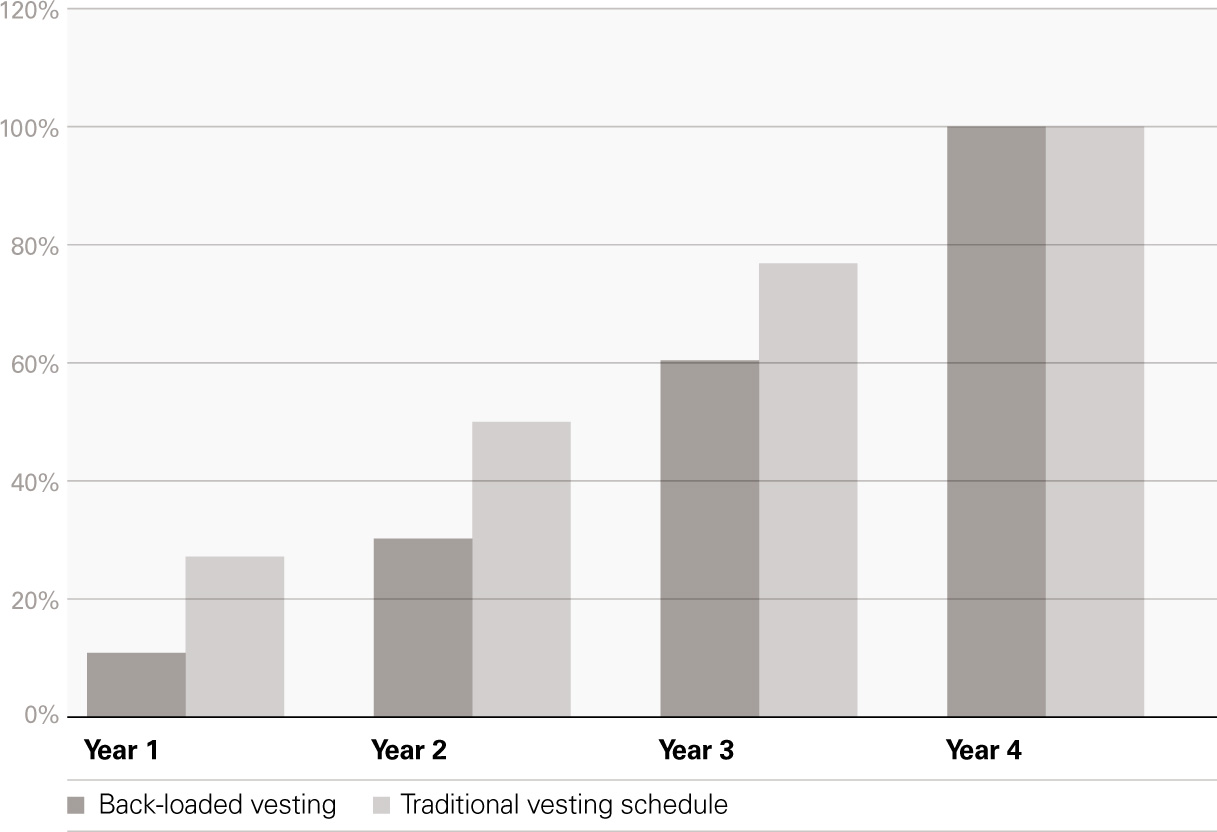

The traditional four-year vesting schedule

A four-year vesting period is standard practice in both the US and Europe, and tends to be the same regardless of role or seniority.

Vesting is generally linear, with 25% immediately following the cliff, 50% after two years, 75% after three years and 100% after four years.

In the US, vesting is almost always monthly after the cliff, for specific tax reasons. In Europe, vesting is often monthly too, but can be quarterly or annual, to reduce administration.

Alternative schedules

In recent years, alternatives to this traditional model have emerged because the time-based formula has been criticised for emphasising the closing of hires, over longer-term retention. The perception is that this has rewarded ‘job hopping’, with employees staying through their cliff, but moving on at the first sign that the company’s growth prospects might not be spectacular.

When an employee leaves a company, so too does their knowledge and experience. Companies appreciate that stock options need to be structured to encourage long- term retention as well as to simply secure hires in the first place.

Falling tenures

In the US, employees aged between 25 and 34 had a median tenure of just 2.8 years in January 2016, compared to 7.9 years for workers aged between 45 and 54, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

This has led to two alternatives to the traditional vesting schedule: back-loaded vesting, and performance-based vesting. We expect to see more examples of European startups experimenting with these options in the coming years.

Back loaded vesting

Instead of giving employees a quarter of their options per year, Amazon gives its employees 10% in the first year, 20% in the second, 30% in the third and 40% in the fourth. Similar approaches have been adopted by Snap and several European companies, including Farfetch.

In European startups, it can make even more sense to introduce a back-loaded vesting schedule for option grants. This is because grants are used much more as a way of retaining, than of hiring talent. Few candidates will question an offer because of a back-loaded vesting schedule. But many may be encouraged to remain at the company in order to maximise their vesting. We encourage European founders to seriously consider back-loaded schedules.

Traditional vs back-loaded vesting schedule

Source: Option Impact from Advanced HR (US data), Index European ESOP survey

Source: Option Impact from Advanced HR (US data), Index European ESOP survey

Performance-based vesting

It’s becoming more common to reward executives with performance-based stock options, rather than time-vested ones. This means employees are only given stock options if they hit targets that drive your long-term value, like revenue growth.

This approach normally comes with two caveats.

First, it only applies to senior executives, in roles that impact your top-line goal, like sales and marketing.

Second, it’s still a good idea to use a traditional, time-based system for up to half of their stock. This is because there may well be external factors outside the control of a single executive which affect performance targets.

Strike price

Go for the lowest strike price

In some European countries, such as Germany, strike prices are set based on the latest fundraising valuation. In others, notably the UK and the US, you can offer grants at a reduced strike price without any tax penalty, by obtaining a ‘fair market valuation’ (FMV), which will be recognised by tax authorities.

While tax-assured valuations may not be available everywhere, get legal advice to see what flexibility is possible. In several countries, whilst valuations may not be tax-assured, there are precedents for offering reduced strike prices, which are unlikely to be challenged later on. Your aim should be to maximise your employees’ upside, without the risk of incurring a large tax bill.

Some founders and investors believe a discounted strike price misaligns employee and shareholder interests. We don’t agree. By obtaining the maximum discount possible, you give employees more financial benefit – and stronger motivation – per option granted. It also recognises that stock options convert into ordinary shares, which are fundamentally less valuable than the preference shares that investors generally hold.

Additionally, if your company goes through a bad patch and you’re forced to take funding at a lower valuation, the options may still be valuable. It is also in your interest to have a low strike price as sophisticated individuals will realise that higher strike prices imply less benefit, and will therefore push for larger grants – using up more of your ESOP.

Issue options at the lowest strike price you can. Maximise the financial benefit to the employee, and therefore the motivational benefit you can get from a given number of options granted.

Neil Rimer

Partner, Index Ventures

Leavers

How to handle leavers’ options

What happens to the options of employees who leave your company before you reach a liquidity event?

The skills you need at the start of your company are very different to the ones you need later on. Sector-specific and managerial skills tend to become more important as your business grows. Company cultures evolve, with an unstructured environment giving way to more refined processes.

You might not need or even want an employee to stick with you all the way to an IPO or exit. And early-hires might also want to move on, for reasonable personal or professional reasons.

The reality is that of your first twenty employees, only four or five on average will still be with you if you scale all the way to an IPO.

Dominic Jacquesson

Director of Talent, Index Ventures

This doesn’t need to be a bad thing. You should acknowledge the contribution these early employees made to get you to your current position, and aim to leave on good terms. This way, your former employee remains an ambassador for your brand.

Facilitating leavers to exercise their vested options is a great way of achieving this. Conversely, preventing them from exercising can be poisonous for relationships.

However, choosing the right policy for your leavers is complicated by questions of taxation, strike price, and headaches that come with having minority shareholders. These challenges vary hugely from country to country, so there is no single ‘right approach’.

US – 90 days

In the US, employees who leave typically have 90 days to exercise vested options. After this, any remaining options are forfeited. In a private company, this means individuals must quickly decide whether to take the risk of using cash to buy an illiquid asset. Depending on the number of options and strike price, this may be unaffordable. In the US, exercising options may also trigger a tax liability, depending on the income of the individual and size of the gain at exercise – even if the shares aren’t immediately sold.

This practice can make leaving a company prohibitively expensive. If an employee joined early, the strike price may be very low – a 60% discount on the last-round valuation is not uncommon – but exercising options can still be expensive. In the example we used earlier, an employee granted 1% of FDE as options at seed stage, at a seed-round valuation of $10m, would need $40,000 to exercise all their options. A tax bill could add to the financial burden. It may be years before the company exits and these shares can be sold – and there’s always the risk that the company loses value, or fails.

A few US companies are now adopting extended exercise periods, to appeal to savvy candidates who understand the implication of leaving before an exit. For example, employees may be given an additional year to exercise, per completed year of tenure after their cliff. This approach gives the employee time to secure the cash to exercise, and to better gauge the company’s trajectory. It thereby helps to build an employee-friendly culture and attract new hires.

Analysis we’ve conducted shows that even when company valuation has increased more than 10x, only 60% of leavers in the US actually exercise when they leave a company. The remainder forgo the opportunity to make potentially terrific returns, often because they lack the cash resources to exercise so quickly.

Henry Ward

Founder & CEO, Carta

Europe

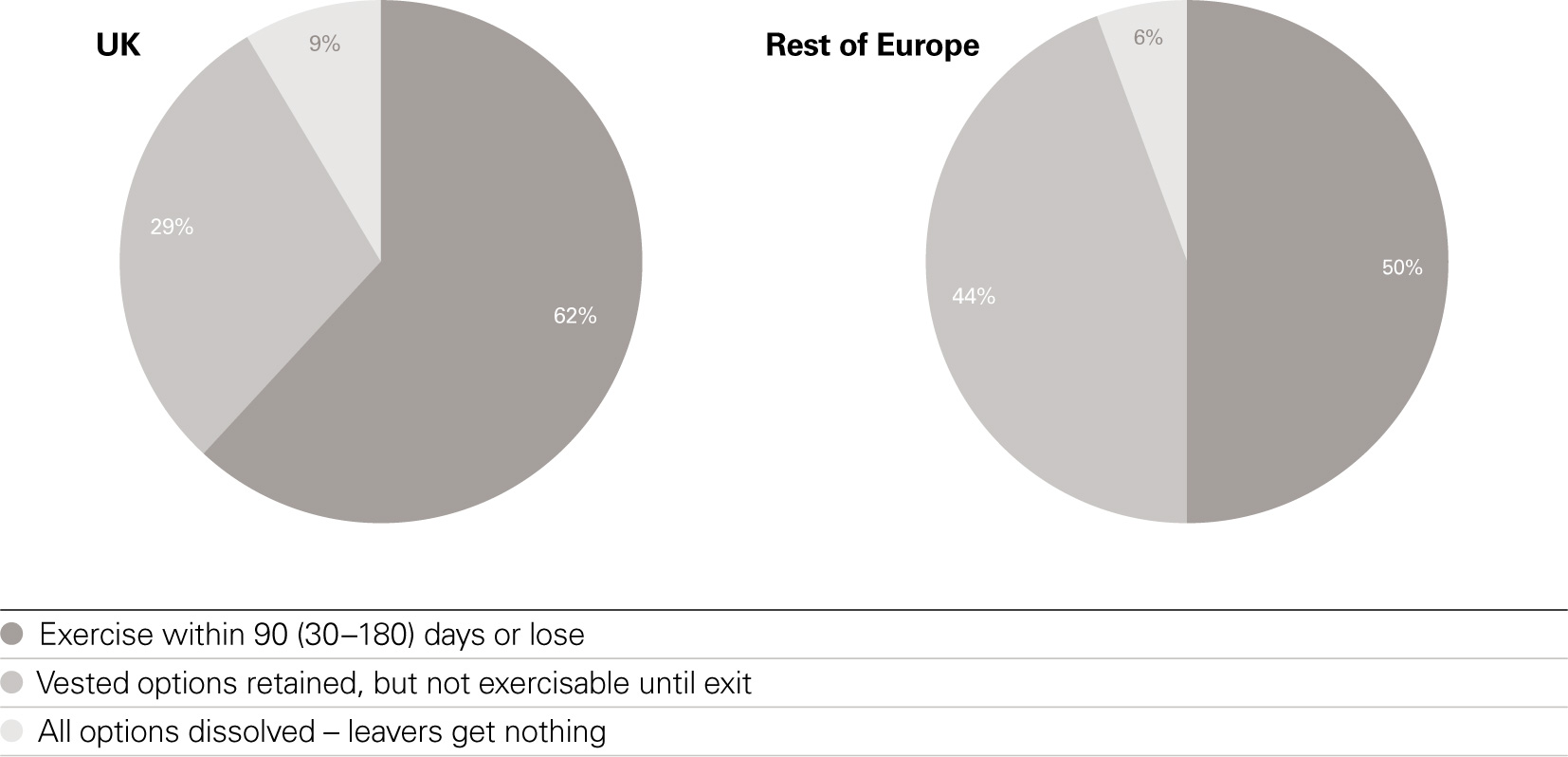

Our survey of European startups shows a more mixed picture than in the US. As you can see in the chart below, almost half of European startups (particularly outside the UK) allow leavers to retain their vested options, but without the right to exercise them until exit.

That’s because, in much of Europe, minority shareholders must be consulted ahead of major company decisions. If leavers exercise their options immediately, the number of shareholders grows, which can create major administrative headaches.

Furthermore, strike prices in most of Europe are high, and tax liabilities after exercise can be much higher than in the US.

Allowing leavers to retain their vested options avoids both these problems, but it leads to a perverse incentive. In effect, leavers benefit from continued increases in the share price, with neither personal involvement or financial outlay, since they don’t have to pay for their shares upfront.

These factors rarely apply in the UK – but even so, more than 25% of startups offer the same terms.

On the other hand, a few companies in our ESOP survey have the drastic policy of dissolving all options for leavers, whether vested or unvested.

We advise that you tailor your leaver policy according to the specific situation in your country. Your guiding principle should be generosity, wherever possible, giving leavers a realistic opportunity to exercise and become shareholders.

But also try to avoid situations where leavers retain all the benefits of staying at zero cost. One innovative solution, for example, is to allow leavers to retain vested options without exercising, but to ‘cap’ the upside that they can achieve – e.g. applying the share price in the funding round immediately before or after they leave.

What happens to stock options held by leavers?

Source: Index European ESOP survey

Source: Index European ESOP survey

Good and bad leaver provisions

ESOPs provide mechanisms for cancelling the exercise rights of ‘bad’ leavers. In Europe, this mechanism is often discretionary. People fired for major disciplinary breaches, or who leave to join a direct competitor, almost always fall into this group. Quite often it also applies to those who simply choose to leave, or those terminated for poor performance.

It’s very different in the US, where there are very tight restrictions on who is considered a bad leaver; typically involving dishonesty, fraud, negligence, or breach of confidentiality. In fact, bad leaver provisions for stock options are usually tighter than those in employment contracts or covering health and pension benefits. Options are considered a core part of an individual’s compensation, and cannot be clawed back by the company.

We strongly support founders following the US approach on leavers, to reassure employees and demonstrate the real value of options. As stated earlier, if employees become cynical about your options program, it ceases to be a benefit, and in fact can become symbolic of a poor culture. Thankfully, we’re now seeing companies in Europe following this advice, and reducing bad leaver provisions.

Change of control and acceleration provisions

Minimise accelerated vesting

ESOP rules will spell out what happens to employee options during a change of ownership – i.e. a merger, acquisition or IPO. In such a scenario, standard US ESOP terms dictate that vested options become exercisable. New owners purchase them on the same terms as they are offered to all shareholders, whether that means cash, shares in the new company, or a mixture of the two.

During an IPO, shares from exercised options become tradeable shares in the listed company. Unvested options will generally continue to vest following IPO.

In an acquisition, an acquirer will typically put in a new retention programme for key employees, and unvested options lapse.

Exceptions are sometimes made for key executives, or the executive team as a whole. In particular, the CEO, CFO and General Counsel are often subject to acceleration provisions, which partially or fully accelerate the vesting terms for their option grants. This is because these individuals are critical to a successful exit. Without acceleration rights, they have an incentive to delay until their options are fully vested.

In such cases, there’s usually a ‘double-trigger’ acceleration provision: acceleration only happens if there’s both a change of control and that individual is terminated or demoted. This protects against new owners who terminate – or effectively terminate – key executives after taking control, thereby preventing them from vesting further options.

Acceleration without a double trigger, and acceleration for non-executive staff, are both rare in the US. They reduce the sale proceeds for each common stock shareholder and as a result are deterrents to potential acquirers. In fact, the risks can be even higher for an acquirer, since your team is often the most valuable asset that they are paying for. If key members of this team stand to make unexpected additional gains at the moment of acquisition, the risk that they choose to leave the company is particularly high.

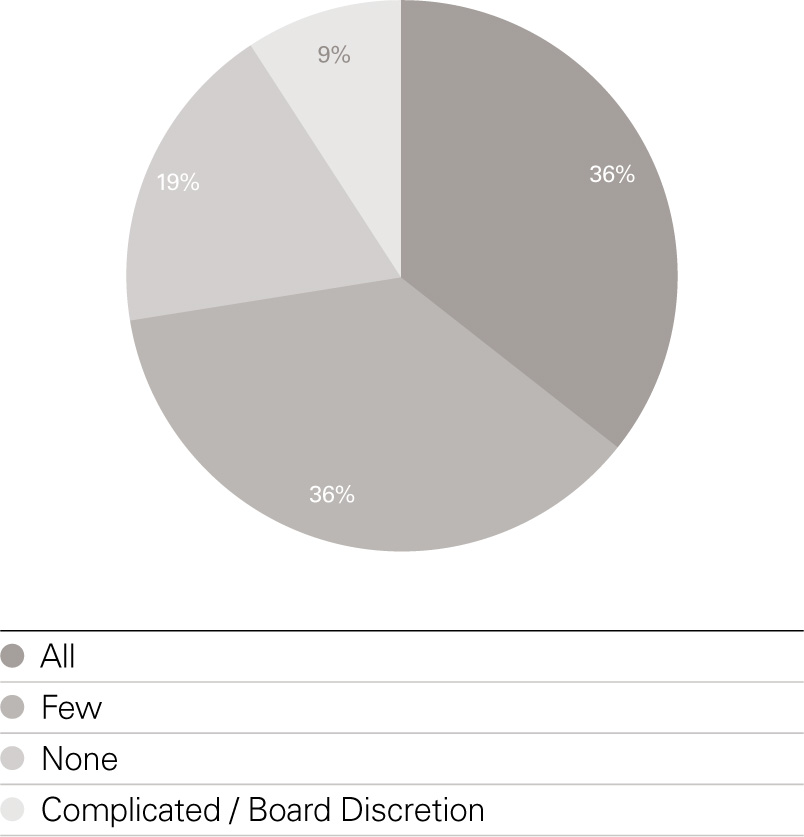

The European picture is different. One third of European startups offer full accelerated vesting to all employees, which would be unheard of in the US. It’s not clear why this is, but it seems to have become standard wording in many legal templates.

We recommend at most, double-trigger partial acceleration limited to the executive team only. A broader acceleration policy could seriously impede your chances of a successful exit.

You cannot over-estimate how big a deal vesting acceleration rights can be. They can make or break an acquisition. And granting different acceleration rights across an exec team are a recipe for rancor when you get to your exit.

Clint Smith

SVP Corporate Development & General Counsel, DataStax

All-employee acceleration is bad practice because you are sending the message that an acquisition is the end of the road. Buyers would definitely disagree with that.

Dominique Vidal

Partner, Index Ventures

Which employees benefit from acceleration provisions? — In Europe

Source: Index European ESOP survey

Source: Index European ESOP survey

Option grants at seed

How much, and who gets it?

It’s not easy to determine how much equity employees should get – particularly if you’re a first-time founder. In Europe, there’s not much benchmark data. Often, all you have is a gut feeling, and the views of a small handful of advisors. This chapter, and the next, aims to close this critical knowledge gap.

When it comes to employee stock options, there are a few big questions that almost all founders ask, regardless of sector, stage or market:

-

‘How much equity should I give to new hires?’

-

‘How do I deal with the differing expectations for different roles?’

-

‘How do I design a system that will be consistent and fair in the long run?’

In this chapter, we will address this set of questions at seed stage. In the next, we will move on to consider grants for Series A employees.

At seed stage, you are unsure of who is going to continue the adventure with you. We also see a lot of role and title inflation going on at this stage, which is best avoided.

Reshma Sohoni

Co-founder and General Partner, Seedcamp

Striking a balance

At seed stage, you will be hiring your first few employees – probably no more than ten.

Your company will have few formal processes. You’ll still be iterating your product offer, target market, and business model. So your employees will need to be highly flexible. You won’t necessarily have formal hierarchies or job titles, as you’ll still be figuring out both the skills you need, and the skills you have in your current team.

Compensation packages for your early team need to strike a balance. On the one hand, money will be tight, which makes options an attractive way to compensate your team. On the other, you don’t want to give away large chunks of your business to people whose contribution is unproven.

This is a conundrum, and it comes at a time when you want to be focusing on your product. So, like many aspects of running a startup, it can feel more like an art than a science.

The dangers of IOUs

Think twice before making vague promises

In the US, it’s common for companies to establish a formal ESOP as part of their seed funding round, and to start making formal allocations and grants. In Europe, where the costs and complexities of ESOP setup can be greater, this is less likely. However, it is becoming more popular, and we recommend it whenever possible. Increasingly, experienced talent will not join a company without a formal stock option offer.

It’s easy to run into problems with option grants when you have no formal ESOP in place. Any agreement you make is essentially an IOU – a loose commitment to offer something in the future.

This means you should be extremely careful, ensuring that any offer is clearly understood by both parties. Some founders make the mistake of agreeing equity terms on a handshake, and while this is often done in good faith, it can come back to bite either party.

When entrepreneurs make loosely-defined promises to their employees, it can be an absolute nightmare.

Sarah Anderson

Director, RM2

Best practice: dos and don’ts for early stage equity discussions

Do

-

Let your employee know roughly when the grant will be made, and when they can expect to see formal terms

-

Be clear on whether the grant is based on a percentage of the company’s FDE before or after the next fundraise

-

Consider backdating the vesting period to when the employee started working with you

-

Aim to give yourself maximum room for manoeuvre, while still reassuring employees

-

Keep comprehensive records of any verbal agreements regarding future option grants

Don’t

-

Make promises you might not be able to deliver on

-

Be vague to the point that your employees are confused or demoralised

-

Make detailed or open-ended promises in writing

-

Link grants in any way to business metrics, growth or valuation

ESOP due diligence at seed or Series A

You’re required to disclose all option grants promised to your existing employees. Make sure you factor these into the allocated portion of your ESOP,tobeclearonhowmuch unallocated ESOP remains.

The Family: Bootstrapping pre-seed by using employee equity

Founded in Paris: 2013

No. of portfolio companies: 231 active startups

Index initial investment: Seed, 2013

Offices: France, UK, Germany

Moving at startup speed, The Family transforms portfolio startups, special projects and virtual infrastructures into a highly connected community of entrepreneurs, operators and fellow investors across Europe.

Few European startups offer equity to all of their early employees, and co-founder Oussama Ammar sees this as a big mistake.

Too many European entrepreneurs underestimate the psychological impact of having everyone onboard

The Family doesn’t just encourage stock options: it insists that every startup it invests in creates a plan.

It’s one thing we feel really strongly about.

The team recommends startups allocate 20% of their options pool during their seed round, convincing investors to increase their pre-money valuation to accommodate this carve-out.

We like a standardised approach. In Europe, there are too many custom decisions, which slows things down and makes employees wary. We’ve been running training sessions for lawyers in Paris and Berlin to help them understand that dilution caused by stock options isn’t a bad thing that they should stop their clients doing.

The Family takes equity incentives so seriously that it has created Ekwity, a dedicated subsidiary to advise European startups on how to structure employee equity plans so that everyone is happy, committed and actually understands what they own.

Grants for very early stage companies

Formalised ESOP plans are becoming more common in European seed companies, as the market matures, and competition for talent rises. Founders still wonder how much equity is enough and how to properly size their ESOP. They usually now adapt Series A standards. Mirroring the US, The Family sees seed rounds in Europe looking more like Series A rounds of past years. And pre-seed is what seed used to be. Equity is therefore becoming a hot topic for pre-seed companies struggling to attract early hires when cash is particularly tight.

Pre-seed stage

Pre-seed startups haven’t yet raised funds with institutional investors and business angels.

Pre-seed founders rely on small amounts (usually less than €100k) of cash, coming from personal savings, or from family and friends.

Building revenues early to master your ownership and ESOP

The Family encourages founders to avoid the 20–25% dilution that comes with a seed round, and to go directly to a Series A whenever possible. They give an example of a pre-seed portfolio company with sufficient revenue to support a team of twenty, leveraging a 20% ESOP. It is now raising a €5–10m Series A.

Option grants for key hires at pre-seed

Option grants are made case-by-case, but The Family cautions against being greedy, offering these early hires sufficient equity upside to compensate them for the risk they are taking. It also suggests two approaches for bringing some science to the art:

First is Paul Graham’s equity equation 1/(1–n) according to which:

Whenever you’re trading stock in your company for anything, whether it’s money or an employee or a deal with another company, the test for whether to do it is the same. You should give up n% of your company if what you trade it for improves your average outcome enough that the (100- n)% you have left is worth more than the whole company was before.

Second is to apply a ‘sweat equity’ formula to attract and compensate key contributors who are working for free (or nearly free).

Example:

-

Contributor market-value: €500 day-rate

-

Time offered for free: 90 days

-

Risk co-efficient: 1.0

-

Notional valuation: €3m

Sweat equity grant

= 500 x 90 x 1.0 / 3,000,000

= €45k (1.5% of FDE)

This would be a special grant, topped up if the contributor becomes a permanent employee after a later fundraise.

Three Takeaways

-

Be transparent to avoid confusion

-

Ensure employees have the financial knowledge to understand your offer

-

Create rules that encourage fairness and retention e.g. cliff > 12 months

Transparency is fundamental to a healthy startup. If a remuneration policy needs to stay secret, there’s something wrong with it.

Rather than treating stock options as an ad hoc incentive, they should be a core part of your remuneration package.

Allocation considerations and benchmarks

How much to give to early employees?

On average, startups that approach us for seed funding have ten employees – but it can be anywhere between zero and twenty. This early talent may well determine the company’s ultimate success or failure. They are also the ones taking the biggest personal risk.

If they’re experienced software engineers, or have taken a large pay cut to join, they will likely expect some level of ownership, even in Europe. Four or five of the first ten employees in a typical European tech startup could be experienced technical hires. So you’ll probably be forced to think about equity, even if you can’t grant formal options yet.

There’s no definitive answer here. But US benchmarks for seed-stage option grants (see table below) can be a useful guide – bearing in mind that European employees are generally less willing to compromise on cash compensation in return for more stock options.

Salaries have a natural ceiling at seed stage, due to cash constraints. This even extends to Silicon Valley, with an the upper-limit of $120k, even for ex-Google engineers previously earning $200k+. For experienced hires such as these, the only way to compensate them is through generous stock option grants. In Europe, $80–90k (€75k, £65k) sets a more realistic ceiling for top salaries.

European candidates on average are more risk-averse than those in the US, and may be less willing to compromise on salary. For junior hires, salaries tend to be closer to market value, since people still need to pay their bills. Stock options awards are correspondingly lower.

The size of your seed round also has a big impact. Seven years ago, seed rounds were less than $1 million, creating a very strong downwards pressure on salaries, the largest cash expenditure for most startups. Nowadays, seed deals can sometimes look more like a small Series A, with $4 or $5 million raised. This gives more flexibility for hiring plans, and salaries.

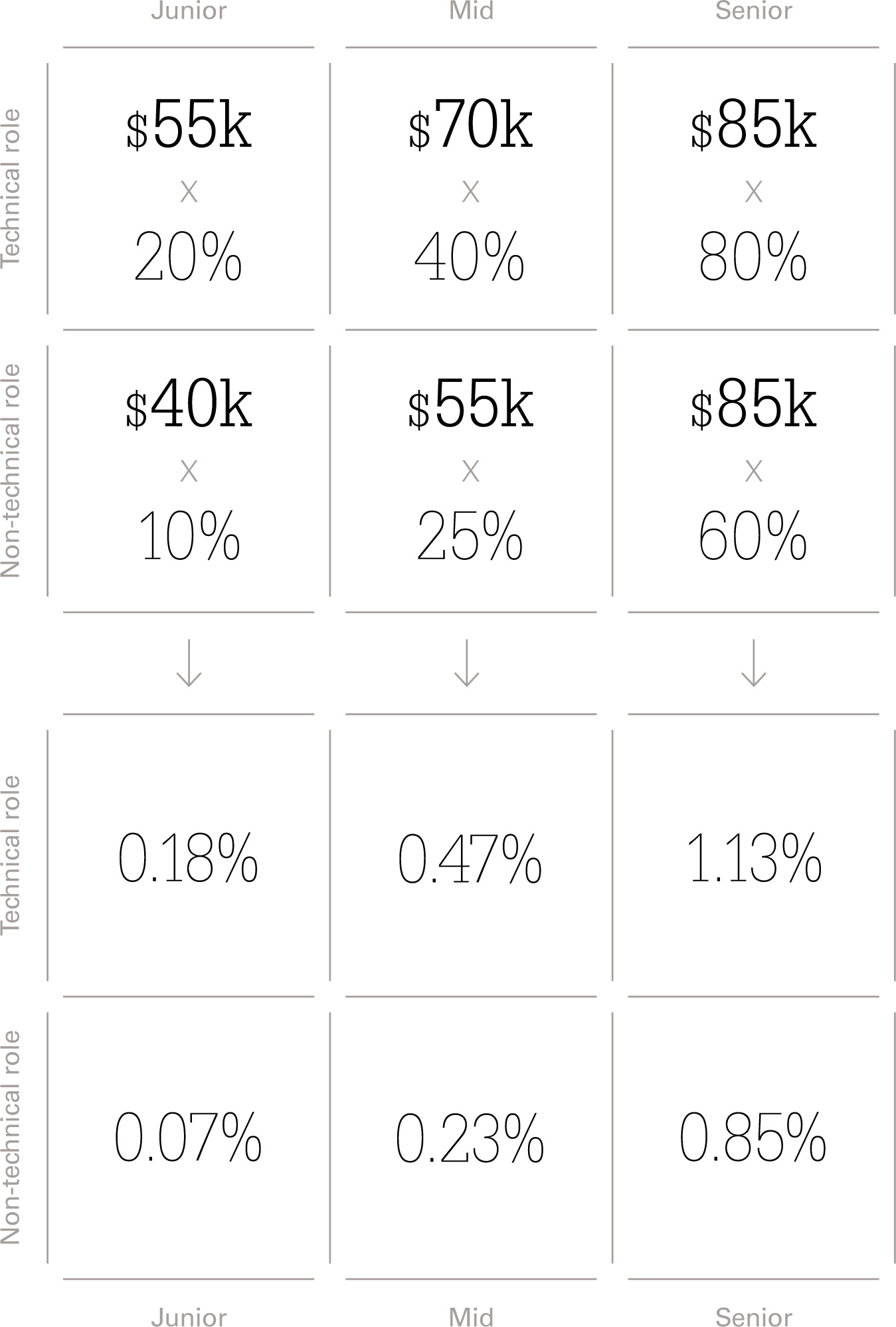

The grids below provide potential salary levels and option grants expressed as a percentage of salary. We believe these values are realistic for a European seed startup with ambitions to succeed in attracting quality talent. But it’s important to remember that there is no magic number.

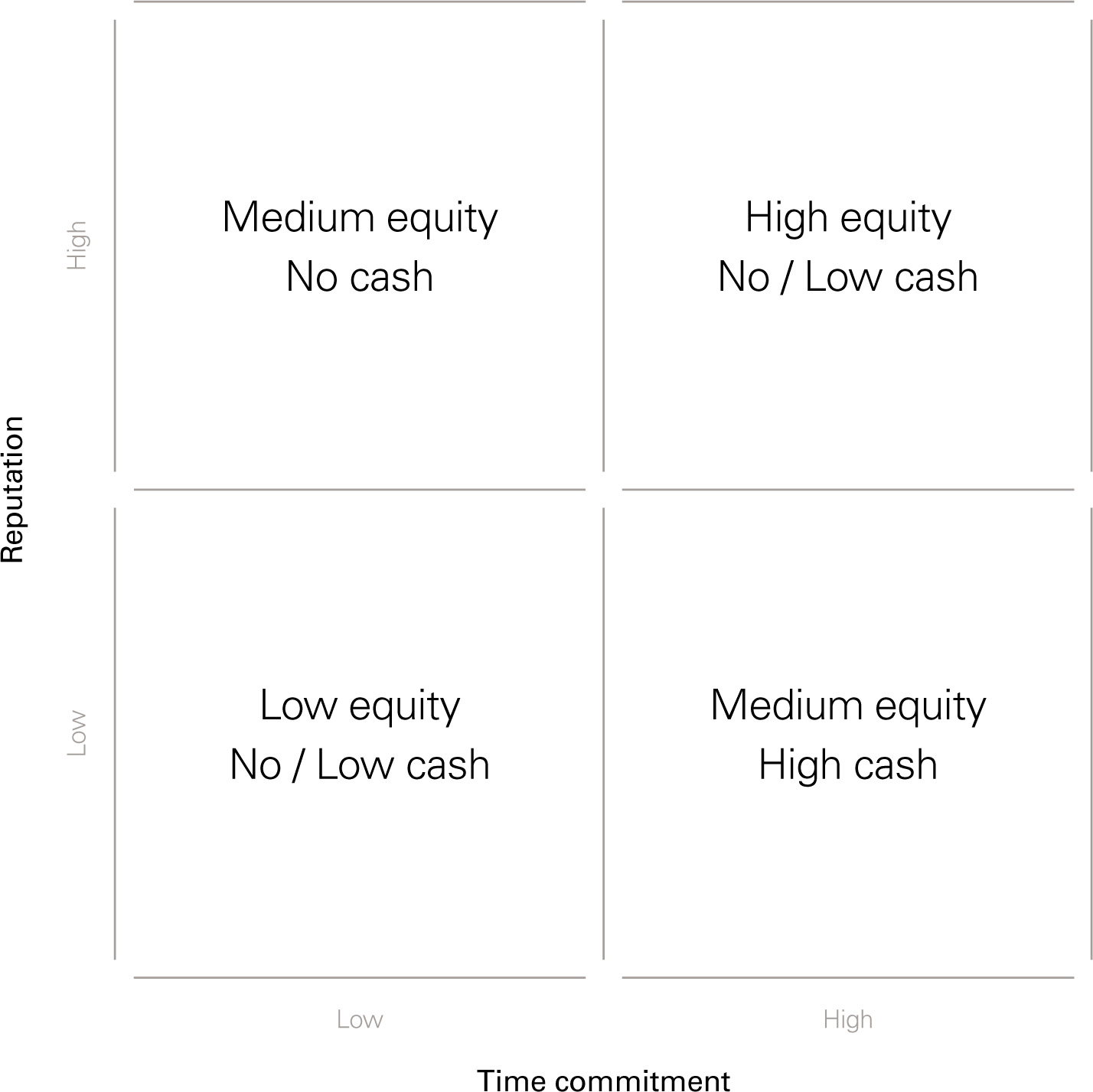

Calculating initial grants

Our OptionPlan app will help you

We have developed a 6-box grid to help you calculate grants for employees below executive level – the two axes being seniority and technicality. We have also benchmarked salary information to get you started.

We encourage you to use our OptionPlan app to compare a set of six benchmark percentages for seed startups, and how these translate into grant sizes, ownership, and potential upside value.

Visit www.optionplan.com

| Level of employee | ||||

| Senior | Mid-level | Junior | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company function | ||||

| Engineering | Cash | $120k | $100k | $60k |

| Options | 1.00% | 0.45% | 0.15% | |

| Product & Design | Cash | $100k | $90k | $50k |

| Options | 1.00% | 0.45% | 0.05% | |

| Business Development | Cash | $100k | $90k | $50k |

| Options | 0.35% | 0.10% | 0.05% | |

| Community & Marketing | Cash | $70k | $70k | $50k |

| Options | 0.9% | 0.25% | 0.05% | |

Potential salary and option grants as percentage of salary in European seed company (top graph), resulting in implied ownership as percentage of FDE at valuation of $6m (lower graph)

Significantly larger grants, at the 2% or even 3% level, might make sense in specific situations. For example, if you are a solo founder who needs to hire in a wider range of experienced skill-sets to complement your own. Or a deep-tech company that needs highly sought-after machine learning, AI or VR developers.

For a typical seed team of ten employees, which we include in the OptionPlan default settings, these grants add up to 5% of FDE at a $6m post-money seed valuation. This total of option grants at seed stage is in fact close to the US average, and compares to a current European average closer to 3–4%.

In the US, it would be unusual for employees hired at seed stage not to receive options as part of their job offer. In Europe, it’s probably more like four of the first ten. And it’s not unusual to see no equity promise at all.

We believe that all employees at seed stage should receive stock options in Europe. Grant sizes may be lower than those above, if you are paying closer to market salaries, and if you are in a less mature ecosystem. OptionPlan’s different benchmark settings can help you to gauge the balance correctly.

In the UK, you now have a roster of startups which have achieved exits at values of $100m or even $1 billion. Because of this, candidates are more interested in the idea of stock than in the rest of Europe.

Reshma Sohoni

Co-founder and General Partner, Seedcamp

Dev shops

You may be building your technical team in Eastern Europe, hiring talented engineers from ‘dev shops’ for much less than you could in Western or Northern Europe. These hires will be less likely to take a pay cut in return for stock options.

Option grants at Series A

Once you reach the milestone of a Series A fundraise, you will need to start standardising your approach to stock options.

We suggest a framework which divides grants into five categories:

-

New hires – executives

-

New hires – staff

-

High performers

-

Promotions

-

Retention grants

This chapter details an approach for grants falling into the first four of these categories. Retention grants are covered in chapter 9.

First, we will discuss the principle of granting options to every employee in your team.

Equity for all?

Aligning your team

Should you offer your whole team stock options, or only some individuals? It’s a fundamental question, and one that may come up several times as you grow your business.

The argument for all-employee ownership is simple. It means every hire is invested in your business. It signals that you believe in every employee, and encourages collaboration, and a sense of responsibility. It also means you can address everyone with a single voice – for example, at off-sites and all-hands meetings. Your employees are no longer just employees – they’re co-owners, and this can be a major element of your company culture.

The opposing view, still common in Europe and in late-stage companies, is that many employees prefer tangible benefits – like a bigger salary, pension contributions, health care or a gym membership – to stock options.

All-employee ownership levels by stage

Source: Option Impact from Advanced HR (US data), Index European ESOP survey

Source: Option Impact from Advanced HR (US data), Index European ESOP survey

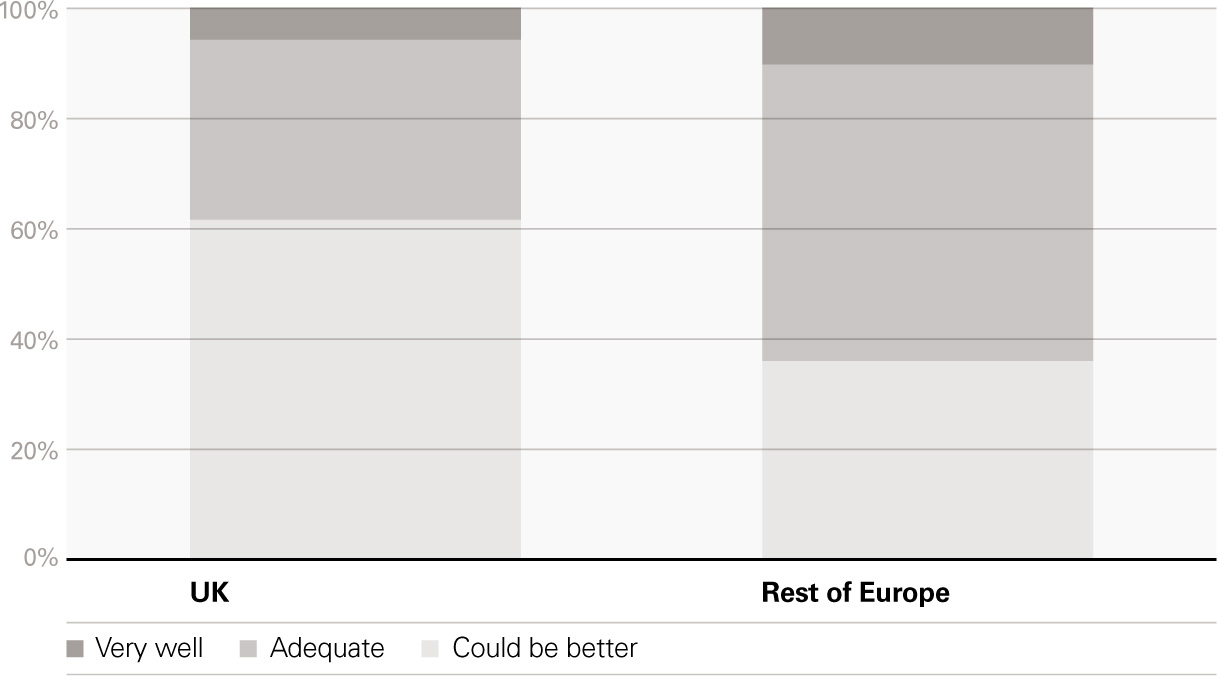

Unsurprisingly, our research shows that all-employee ownership in Series A/B companies is most common in the Bay Area, at 75%. As you move east, this figure drops, to 32% in continental Europe.

For Series C+ companies, all-employee ownership is less common in the US and UK. This isn’t surprising: the collegiate feel of a startup diminishes as it grows, and the diluting effect of issuing options to all employees can be significant in a large company. Plus, later hires are likely to include more commercial and support staff, who are typically less attracted by equity.

Interestingly, however, continental Europe shows an inverted trend. Later-stage companies are more likely to have an all-employee scheme here than anywhere else. It seems that, in Europe, large companies use equity to foster a sense of community that is otherwise lost as they grow. This certainly chimes with our experience. In fact, we find a majority of European companies introduces (or re-introduces) an all-employee stock option scheme as they look towards a potential IPO.

It’s up to each founder how they approach employee stock options. But we strongly believe making a small grant to every new hire regardless of role, at least up to Series C, can bring huge benefits. Something like 5% of base salary works well. This award would not apply to employees who receive a larger grant as part of their package, such as C-suite employees.

Farfetch for All: using employee ownership to recognise and reward a whole team

Founded in London: 2008

No. Employees: 1,500+

Index initial investment: Series B, 2011

IPO on NASDAQ: September 2018

Offices: UK, US, Japan, Portugal, Russia, China, Brazil

Farfetch is the global platform for luxury fashion, connecting customers in over 190 countries with an unparalleled offering from the world’s best boutiques and brands from over 40 countries.

All quotes:

Sian Keane

Chief People Officer

For years, Farfetch granted options only to very early stage employees and senior hires, and on an ad hoc basis to high performers, without a robust methodology.

We needed a programme that would foster a feel- good factor and unite the whole team under a common goal. If we succeed, the company succeeds – and vice versa.

Since January 2017, every full-time Farfetch employee is offered an option grant.

More than just a token gesture

When it came to deciding on option grant sizes, Sian recalls:

We conceived a successful exit for the business, and considered what a meaningful payout would look like for employees at each career level.

They decided not to take tenure and performance into account when it came to option grant sizes.

Otherwise, decisions would have had to be made on a case-by-case basis. Fortunately, the option grants ended up broadly correlating with salary differences.

Communication is key

When it comes to introducing a new company-wide programme, internal communication is crucial.

We were not prepared enough.

Farfetch Founder and CEO, Jose Neves, announced the programme at the company’s All-Hands meeting, and employees immediately began asking questions. Questions their managers couldn’t answer.

Not everyone understood. Even the managers didn’t have all the information.

Farfetch knew most employees would struggle to understand a formal legal document. So they produced a simple five-page booklet, explaining the key points. They gave the programme a catchy name – Farfetch for All – and branded the booklet in their house style to make it more engaging. This proved to be a big hit with the team.

A recruitment tool

Not only has the programme motivated the existing team, it has also helped recruit new talent.

People come to interviews knowing about Farfetch for All. And if they don’t, we talk about it when they join. It has become a key part of our culture and our employer brand.

The next step

The Farfetch team forecast growth over the next three years, and plan to add options through equity-retention programmes on an annual basis.

We’ve created a pot for top-ups, specifically for high contributors after the two-year vesting mark

Lessons from Farfetch

Even though they implemented their all-employee equity programme further down the line, the success of Farfetch’s approach proves it’s never too late to make an impact.

Upfront vs delayed grants

Delayed grants can help you optimise for performance

You also need to decide when employees receive stock options. In the US, they’re almost always part of the offer package. But in Europe, fewer candidates expect them – which gives you more flexibility.

Overall, we recommend being consistent for any particular function. Avoid upfront grants unless there’s a compelling reason to offer them.

In certain roles, new hires will probably expect an option grant upfront. Such grants usually form a major part of compensation for executive hires (C-suite and VP-level), and individuals will almost certainly negotiate this before they join. For these roles, you should always offer the option grant upfront.

Some software developers, if not all, will ask about stock options before they join. Especially if they’ve worked at startups before, or if they’re in a major startup hub. To keep things simple and consistent, we suggest granting all developers upfront options too. Other technical hires, such as product managers and data scientists, may expect the same, but the picture varies more by location.

Holding off on upfront awards for new hires in other functions has one big benefit: you can find out who the real stars are, and compensate them later accordingly. This helps you to hold on to your best people, and keep them motivated. US companies rarely have this luxury – but in Europe, with the likely exception of executives and technical hires as discussed above, you can design a system that truly rewards performance.

We recommend reviewing new hires at 6 or 12 months, and tailoring their equity package based on their performance. Depending on your rate of hiring, you may want to make this an annual or bi-annual exercise for all staff. Later in this chapter, we’ll walk you through a suggested model for both reviewing performance, and for calculating appropriate grant sizes.

Giving a big upfront grant makes it hard to optimise for someone’s actual contribution. You don’t really know how good someone is when you hire them – but you know a lot more about them a year or two in. In the US you are usually forced to make a maximal grant when the individual is hired based on their title, but it is far better to dole out the equity over time based on the person’s actual contribution not their title.

Clint Smith

SVP Corporate Development & General Counsel, DataStax

Allocation by seniority

Balancing executive and staff equity

Once you’ve secured Series A funding, one of your core challenges will be to scale up. You may bring in new types of talent – particularly ‘go-to-market’ functions (sales, marketing, customer success) and support teams (recruiting, finance, business operations). You’re also likely to make your first executive hires.

This raises a question: how do you allocate options based on seniority?

European companies tend to allocate a high proportion of their stock options to executives – approximately 2⁄3 of the total in late-stage startups. In the US, this ratio is reversed. This reflects the fact that many European employees receive no options at all.

How option grants are split between non-founding executives and staff by funding stage in the US

Source: Option Impact from Advanced HR

Source: Option Impact from Advanced HR

New Hires – Executive grants

Equity for your C-suite and VPs

Executives include ‘C-suite’ employees and VPs. We recommend calculating executive grants as a percentage of your fully diluted equity (FDE).

Most Series A and B startups have no more than three true non-founding C-level executives – some combination of:

-

CTO (Chief Technology Officer)

-

CFO (Chief Financial Officer)

-

COO (Chief Operating Officer)

-

CMO (Chief Marketing Officer) and

-

CRO (Chief Revenue Officer)

A grant set at 1% of FDE for each would be typical in both the US and Europe for each of these roles. But there are exceptions, particularly for COOs and CTOs.

| C-level | VP-level | |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership range | 0.8 –1.5% | 0.3 – 0.8% |

| Number of execs | Maximum of three true C-level execs as you scale | Could build a team of five to eight VP-level execs |

| Upside of %1bn exit | $10m* | $3–8m* |

You should bring in one phenomenal individual every year at exec level – and it needs to be a person you could not have hired the year before. Don’t miss the opportunity.

Dominique Vidal

Partner, Index Ventures

COOs

Equity for COOs can reach 1.5% or even 2% — and it can happen as late as Series C. That’s partly because the nature of the role varies hugely from company to company. If you’re hiring a COO, carefully evaluate how complete their skill set is. Are they assuming overall responsibility for the day-to-day running of the business? Do they have proven experience in scaling startups?

CTOs

CTO equity is correlated with a company’s geography and technical DNA. For Series A or B, 1% is typical in the US, and 0.7% in Europe. This reflects the higher pro-portion of tech-enabled business, particularly in e-commerce, in Europe. In the US, there are more pure software businesses, where proprietary technology is the key differentiator.

VPs

VP grants vary widely based on experience, and the importance of their function. As a rule of thumb: 0.3 – 0.8% of FDE at Series A, or 0.2–0.7% at Series B, works well. Product and engineering roles will be at the high end of this scale, whereas HR and Finance will attract smaller grants. VP Sales will also be lower, because commissions are typically a large part of their package.

Following your Series A, you might expect to hire around four executives: three at VP-level, and one at C-suite. As you scale towards Series C+, a team of 6 –10 VP-level executives is typical.

Executives don’t typically receive top-up option grants for high performance. Instead, they negotiate option grants up front, the value of which grows in line with the company valuation.

With the allocations suggested above, you can make a very crude calculation that at a $1 billion valuation upon exit, a C-suite executive with 1% would stand to make $10 million, and a VP executive with 0.3–0.8% would make $3 – 8 million. These figures are before dilution, exercise cost and tax have been taken into account. Nonetheless, this example expresses clearly the scale of the financial opportunity on offer.

New Hires – Staff grants

Options for employees below executive level

We suggest a different method for calculating, and communicating, option grants outside of the executive team. This is because the numbers can be misleading: a 0.05% share of FDE sounds trivial – whereas a grant of $12,500 (the same 0.05% at a $25m valuation) sounds much more compelling.

Instead, your starting point should be base salary. This has two further benefits. Firstly, salary is a reasonable yardstick for the value of each employee. Secondly, it allows you to maintain a standard approach, even with later fundraising. Grant sizes stay the same in cash terms, but the number of options granted automatically declines as the valuation – and therefore share price – increases. This means you offer consistent rewards, but those who joined earliest see the biggest benefit.

After you hit your Series A, you can expect to hire roughly 40 to 50 new staff below the executive level.

| Functions | Level | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Executive roles | C-Suite | 1 |

| Vice President | 3 | |

| Engineering, Product and Business Development roles | Director | 2 |

| Senior | 10 | |

| Individual | 15 | |

| Marketing, Finance and HR roles | Director | 2 |

| Senior | 4 | |

| Individual | 5 | |

| Sales and Customer Success roles | Director | 1 |

| Senior | 2 | |

| Individual | 5 | |

| 50 |

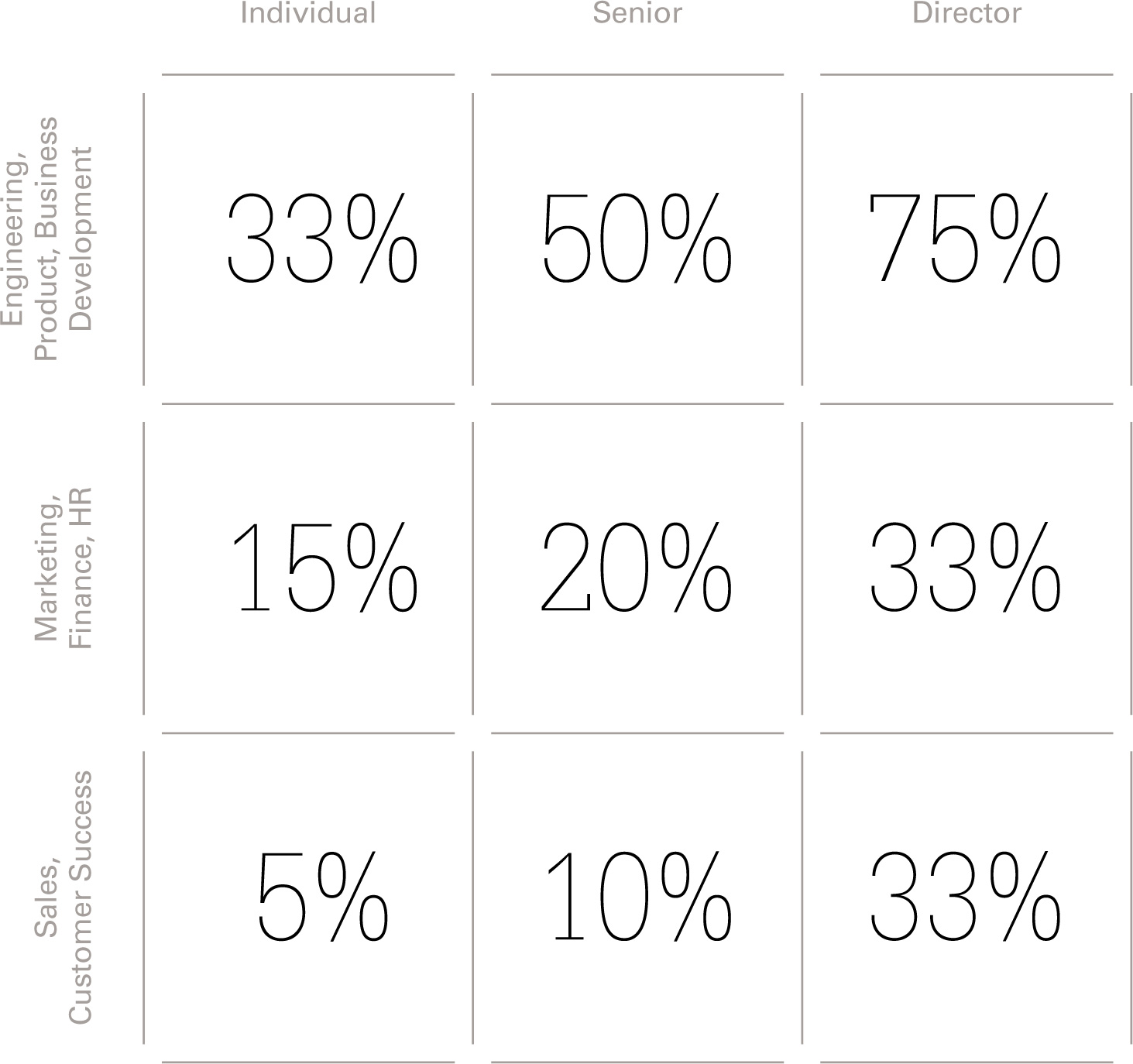

We’ve defined three groupings of functions in this table for guidance, based on what we see in the US in terms of option allocation benchmarks. Those in the first group tend to receive the highest allocations, with declining average allocations for the second and third groups. These distinctions can vary considerably from company to company.

Arrange roles into categories to suit your company’s structure. As you scale, you may well create additional groups to become more fine-grained in your allocations. But avoid this when you’re still a small company (under 100 employees). It will make your option plan more complicated both to implement and explain.

Likewise, there are three tiers of seniority defined here, to keep things manageable for smaller companies. Again, as your team grows, you might want to make more detailed distinctions between levels of staff.