This Man Created The Subscription Economy

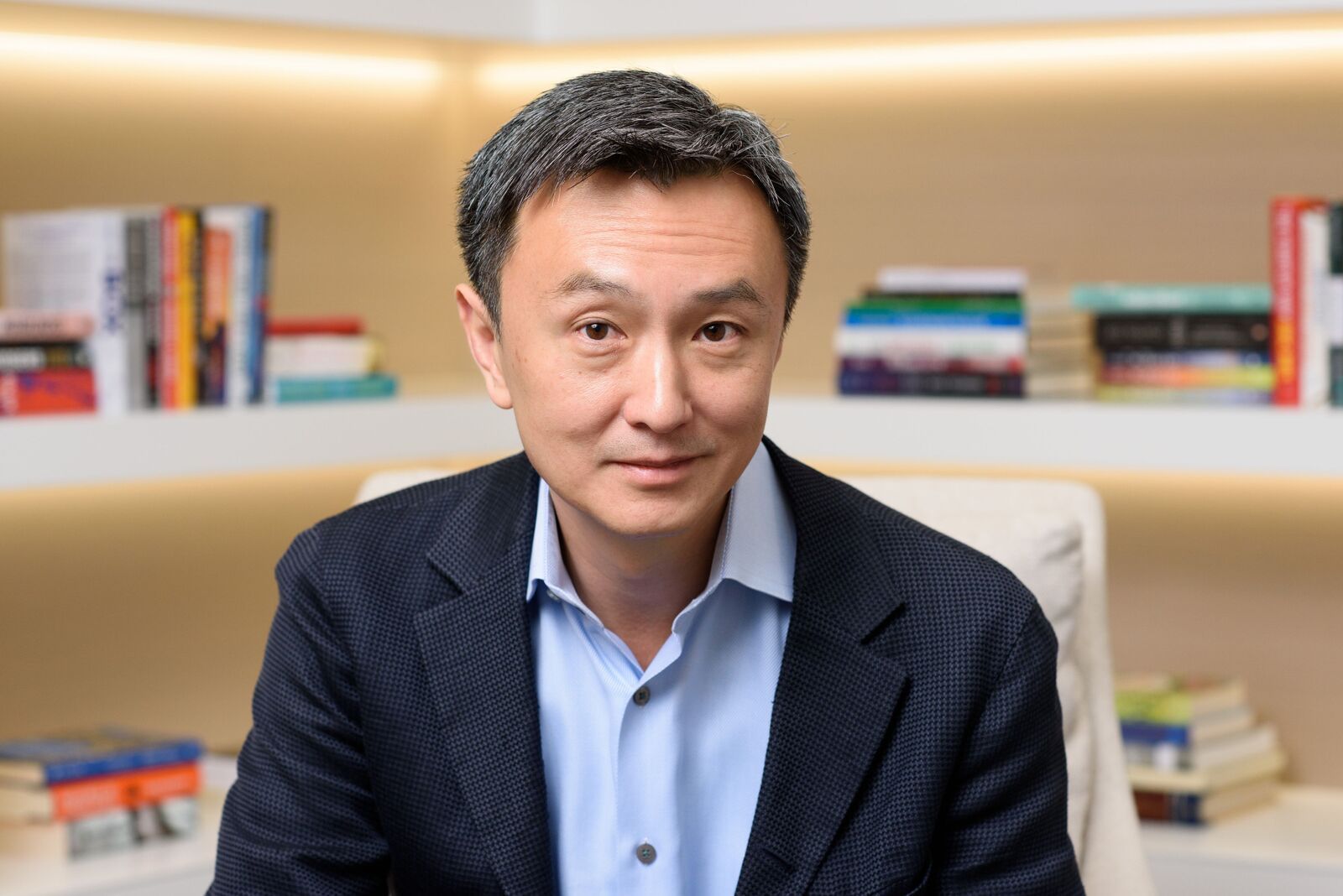

For Zuora founder Tien Tzuo, ten years commitment to a new economy has paid off.

The first thing I noticed when I met with Zuora’s Tien Tzuo was his intensity and focus.

It’s been a year since Zuora’s public offering on New York Stock Exchange. Since then, the company’s conviction in their mission has only increased. As Tien explains his renewed vision of the subscription economy - something he has done several hundred times since he founded Zuora, his subscription business, in 2007 - he seems just as enthusiastic and intensely focused as ever. And yet, he now speaks with the certainty of someone who has been proved emphatically right - ten years and one $1.4bn IPO later.

Tzuo grew up in Brooklyn, New York, to Taiwanese parents. He studied electrical engineering at Cornell before working in sales at Oracle, and then went to Stanford for his MBA. He joined Salesforce in 1999, working in a number of roles before becoming Chief Strategy Officer. When

Tzuo left the company in 2007 to start another business, some were surprised. Why leave a plum job in the inner circle of a booming company for the relentless pressure of startup? Tzuo was employee number eleven at Salesforce, and could easily have retired. But Tzuo had a powerful idea that needed to happen, and he was the guy to do it.

Back then, few people saw the potential of subscriptions, which were associated with old media newspapers and cable, or with software. What Tzuo foresaw inside Salesforce, however, was a much broader shift in which not only were businesses moving from a product to subscription model, but in which society itself was moving from ownership to renting.

“This shift was much more disruptive than just legacy media and software business,” Tzuo explains to me. “You could see the transition happening. Salesforce had disrupted Siebel, Netflix was disrupting Blockbuster, and Zipcar was disrupting General Motors. Maybe that last one seems a bit of a stretch, but if you went to college campuses in New York or San Francisco you’d started seeing an alternative to car ownership. I knew we had the chance to figure out the technology around this, and that it was an opportunity that would just get bigger and bigger.”

I’ve worked closely with Tzuo since November 2011, when Index first invested in Zuora. We’d met shortly before at an intimate conference in Cody, Wyoming, where Tzou had impressed everyone with his very lucid vision and the insights on subscriptions he had learned from Salesforce. The vision didn’t take any persuading - but what did take some persuading was how this would all be implemented. It’s one thing starting a company from scratch using a subscription model, but when you have a business with a more traditional product model, where they sell something once, that’s a much harder transition to subscription. We could see the bumps in the road.

Mike Volpi with Tien Tzuo

These companies needed much more support. They have to buy the Zuora software, then deploy it, which often involves changing the very model of their business. That hurdle was reflected in Zuora’s metrics at the time. The practicality was simply more complex than the vision, so it became critical to shape the company in a way that would help customers overcome that transition.

Tzuo admits than from an investor’s perspective, Zuora may have seemed a little odd. “There was a leap of faith they had to make, because the numbers didn’t convince. Often the reaction to what we were trying to do was binary - you either get subscriptions, or you don’t. And even though VCs are always looking for the next thing, they still didn’t always see it. What we really wanted in an investor was someone who could help us with execution, who was really interested in figuring out how this was going to work.”

Belief was something Tzuo had in abundance, having already experienced and managed exponential growth at Salesforce, as well as the scaling challenges that come with it. He’d already done the journey from powerful idea to billion-dollar IPO, and knew what that felt like. “I simply had the expectation that we should be able to do it,” he says.

From my point of view as a VC, the Zuora opportunity had to be weighed up differently. Every opportunity is different, and this was a much larger canvas. Given the tectonic shift in the economy, the addressable space for Zuora is very, very large.

According to McKinsey, the subscription e-commerce market made $57m in sales in 2011, and by 2016 this ballooned to $2.6bn. More than 3,500 subscription box services have launched in the past few years, offering everything from clothes and make up to art supplies, though 13% of those have already failed in a market that is still finding its feet. Zuora’s own Subscription Economy Index has found that over the past 7 years, companies across North America, Europe and Asia Pacific have seen their subscription-based sales grow by more than 300 percent, representing an 18 percent CAGR; that’s about 5X the revenue growth of an S&P 500 company and US retail sales. Zuora, by being extremely early, has both helped to create the market and become central to it. It’s a powerful position to be in.

Tien’s leadership - his tenacity and doggedness - has been a big part of that. A lot of executives focus on operating, but don’t think about scale. Tien is vision led, so he paints a picture of the future that everyone can follow, whether customers, investors or employees. And while some

CEOs get to a bump in the road and find a different route around it, Tzuo would say ‘We are going after something big. We’ve hit a bump in the road, but we are going to carry on and work it out.’

One big bump in the road came in 2012. Operationally, everything seemed to be in place yet growth had stalled. Despite working closely with customers to implement the Zuora system, half the deployments didn’t go live. “We knew that if we didn’t figure this out, the whole business would collapse,” Tzuo says, bluntly. “At the end of the year we’d wasted $20m and spent more in sales and marketing than the previous year, yet only booked 5-10% more business. We knew something was broken, so we went back to our starting principles and thought about how to build up the model again so that it could scale more effectively.”

A painful deconstruction of the problem revealed that with rapid growth, the system couldn’t replicate because customers’ needs varied so widely. Zuora overhauled its processes so that a number of different sales models helped their customers work through each stage of the transition.

But this process also meant some self-examination for Tzuo, who turned to a leadership coach to help him identify what he could do better. Leadership can amplify good and bad personality traits, and sometimes strategies that work for a small team just don’t scale up. “It took months to identify, but it came down to me communicating better with my executive team,” he says. “The ultimate challenge for leadership is creating an environment where someone can do their best work, where they can be happy and productive and still have room for growth. There has to be a bit of productive tension too, and the cost of failure has to feel reasonable enough to take risks.”

It was during this time that Tzuo and I really cemented our working relationship. At board level, Tzuo explains, it’s too easy to pile in with negative sentiment when companies are working through problems. But blaming one or two people rarely fixes an operational process, especially when the root cause is such rapid growth. “The more educated way is to dissect what has been happening in the business process, evaluate how that could be improved and use the right people to oversee a new solution.,” says Tzuo. “You were detecting and steering the conversation towards a more constructive solution, looking at things in a different way.”

Last year was huge for Tzuo. When Zuora went public in April, some founders told him they had downplayed their IPOs, wary of over-exciting employees and raising their expectations. Tzuo had no such doubts, rolling out a red carpet, champagne and, slightly more prosaically, an IPO-focused Slack channel to answer any questions about the process. It was a very big day. Tzuo’s young daughter rang the Nasdaq bell. Two months later, Tzuo published his book, Subscribed: Why the Subscription Model Will Be Your Company's Future - and What to Do About It, another market-defining moment.

So where does Zuora go from here? How much bigger can subscriptions get? “I really think we’re still in the first phase of subscriptions,” Tzuo says with absolute conviction. “In five years’ time we’re not going to be viewed just as billing and revenue recognition company. I see us as a $10bn company, and I have some ideas… ”

And beyond that, could subscriptions help drive more significant social change? We believe they could. “Take the environment,” Tzuo explains. “Say you rented a phone from Apple instead of buying it, you’d hand it back for them to reuse, recycled or dispose of. The same with a self-driving car, or with nano-technology embedded in your clothes. It means none of this will end up in landfill.”

Beneath Tzuo’s steely, east-coast exterior is a man with a lot of pride in what he has created. “I just don’t think the whole subscription economy would have existed without us,” he says. “We pulled it together and put a name on it. The world is talking about this now, but I still don’t think people know how big subscriptions are going to be.”

Published — April 22, 2019

-

-