The King of Candy: How Riccardo Zacconi and King Conquered Mobile Gaming

For two weeks in the summer of 1985, Riccardo Zacconi worked as a dentist’s assistant. The 18-year-old Zacconi wore a white gown, mask, and gloves. He moved the operating light when the dentist asked him to. He handed over tiny mirrors, scalers, probes.

The dentist was Zacconi’s father, who ran a busy practice in the heart of Rome. Zacconi, fresh out of high school, was adamant about doing something different with his life. He wasn’t sure yet what that would be; in many ways, the not knowing was the point. He told his parents he was considering economics, if only to give himself options down the road. They were supportive, but his father said, “Before you make a decision, I want you to give dentistry a shot.” So for two weeks Zacconi stood by his side, watching him, picturing life as a dentist. All he could see were doors slamming shut, possibilities being erased.

“The thought of knowing from day one what I would do for the rest of my life,” Zacconi says, running it through his mind again years later. “That was horror to me.”

When Antonella Mei-Pochtler met Zacconi at Boston Consulting Group several years later, she wouldn’t have pegged him as a future entrepreneur. Not because he didn’t have the requisite skills, she says, but because he was “so gentle, so nice.” As she got to know him better, she saw traits that foreshadowed his success: his adaptability, his open mind, his ability to listen intently and analyze situations quickly while leaving room for others to thrive. Still, even now she has a hard time reconciling the humble, soft-spoken Zacconi with the famous founder and CEO he later became. “I never saw him be interested in power,” she says.

“I always say choose the path of the unknown.... Whether you’re an entrepreneur or not, the biggest risk is to not take risks. Because then you will never get an opportunity.”

—Riccardo Zacconi

Today, Zacconi’s legacy as an entrepreneur speaks for itself. His company King is one of the world’s most successful gaming businesses, with some of the most popular mobile games of all time. Candy Crush Saga, which at its peak had over 100 million daily active users, has been downloaded more than 3 billion times and driven over $20 billion in lifetime revenue. After going public in 2014, King was acquired by Activision Blizzard in 2016 for $5.9 billion. Zacconi stepped down as CEO in 2019, but King continues to operate as part of Microsoft Gaming with over 200 million monthly active users and more than 2,000 employees around the world.

Looking back, Zacconi credits his success not to being smarter or working harder than others, but rather working alongside great people and treating them the right way. Most important, he says, was learning from his failures and never being afraid to take risks.

“I always say choose the path of the unknown,” he says. “Whether you’re an entrepreneur or not, the biggest risk is to not take risks. Because then you will never get an opportunity.”

Royal beginnings

In 1990, Zacconi found himself, somewhat against his will, in Munich. He was there to research the German economist Eugen Schmalenbach — and he wasn’t thrilled about it.

A few months earlier, at LUISS University in Rome, Zacconi had visited the office of Giovanni Fiori, an associate professor, and asked him to be his thesis advisor. It was an unusual request: Fiori was only 29, young for a thesis advisor. And although Fiori had taught Zacconi in a few classes, he says Zacconi — a shy student, rarely one to put up his hand — was “not the kind of student a professor would notice.” Nevertheless, Fiori was flattered by the request, and they arranged to meet in a few weeks to choose a topic for the thesis.

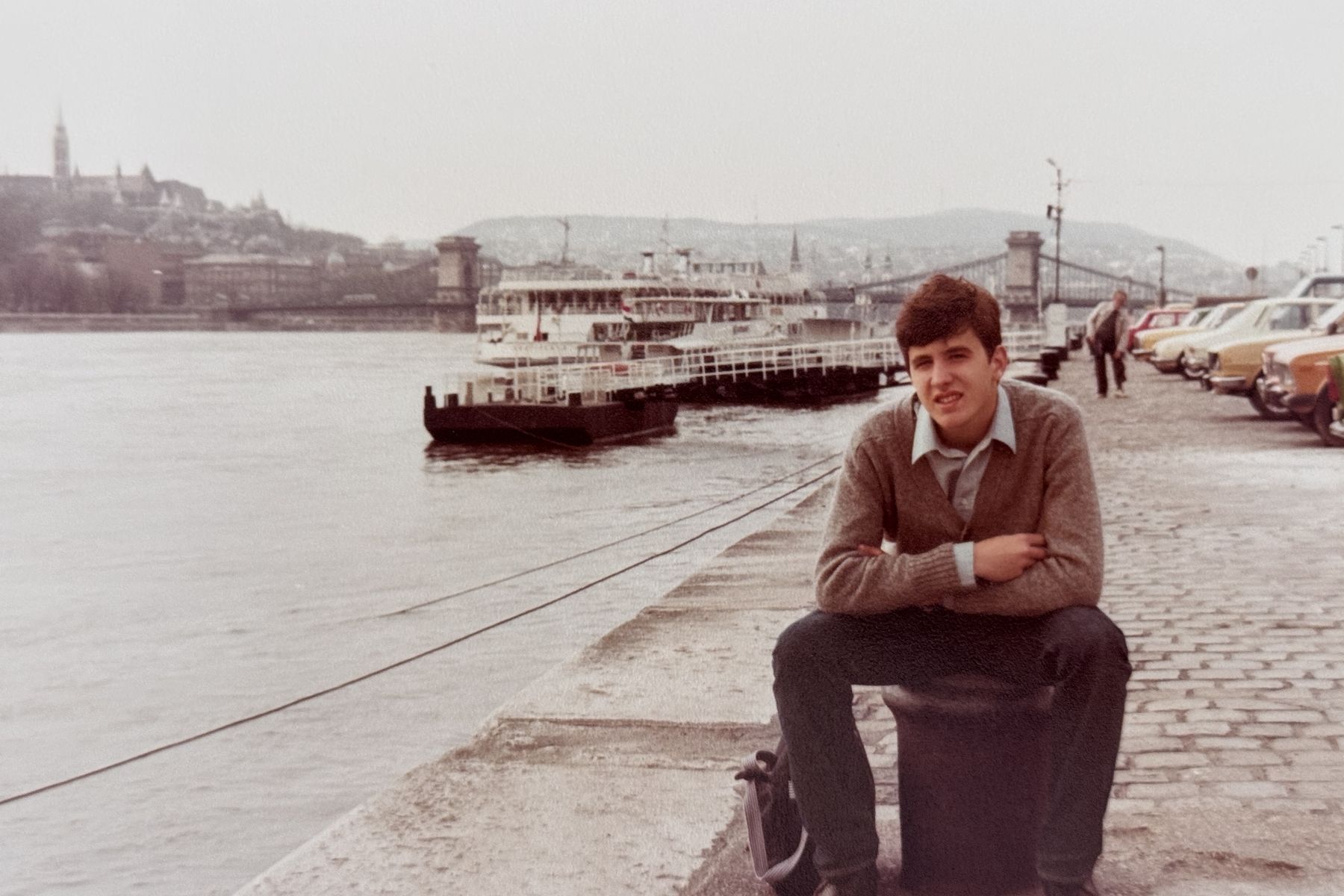

Zacconi during his studies at LUISS University in Rome.

They reconvened in Fiori’s office, where the professor suggested a “very strange and boring topic.” As Fiori explains, “I had been reading about German accounting theories, and I said to poor Riccardo, ‘Why don’t you write about the theories of Schmalenbach?’”

Zacconi was heartbroken. “It was horrible,” he says of the project, still wincing years later. But if he showed his disappointment, the professor didn’t notice. Fiori laughs when he recalls the assignment: “Other students would have pushed back. But not Riccardo. He was always so serious. He just wanted to do a good job and satisfy my expectations.”

“In consulting you work very intensively, and you have a lot of arrogant and extreme personalities. Riccardo was the opposite of that. He was profoundly gentle, humble, pleasant to have around.”

—Giovanni Fiori, LUISS University in Rome

To Fiori’s surprise, Zacconi went to Munich and spent a year there researching the topic. It became a major turning point in Zacconi’s life — not for anything to do with Schmalenbach, but because that’s where he began his career in consulting. At the time, there weren’t many opportunities for Italians to work abroad. Zacconi had applied to a number of global companies, including Apple and BMW, but never heard back. In Munich, he got hired first by L.E.K. Consulting, and then in 1993 by Boston Consulting Group. It was there he caught the attention of Antonella Mei-Pochtler, at the time BCG’s youngest partner and one of few other Italians in the firm. She brought him onto several of her projects, and they connected immediately.

“I found him super bright, reflective, always wanting to learn,” she says. “In consulting you work very intensively, and you have a lot of arrogant and extreme personalities. Riccardo was the opposite of that. He was profoundly gentle, humble, pleasant to have around.”

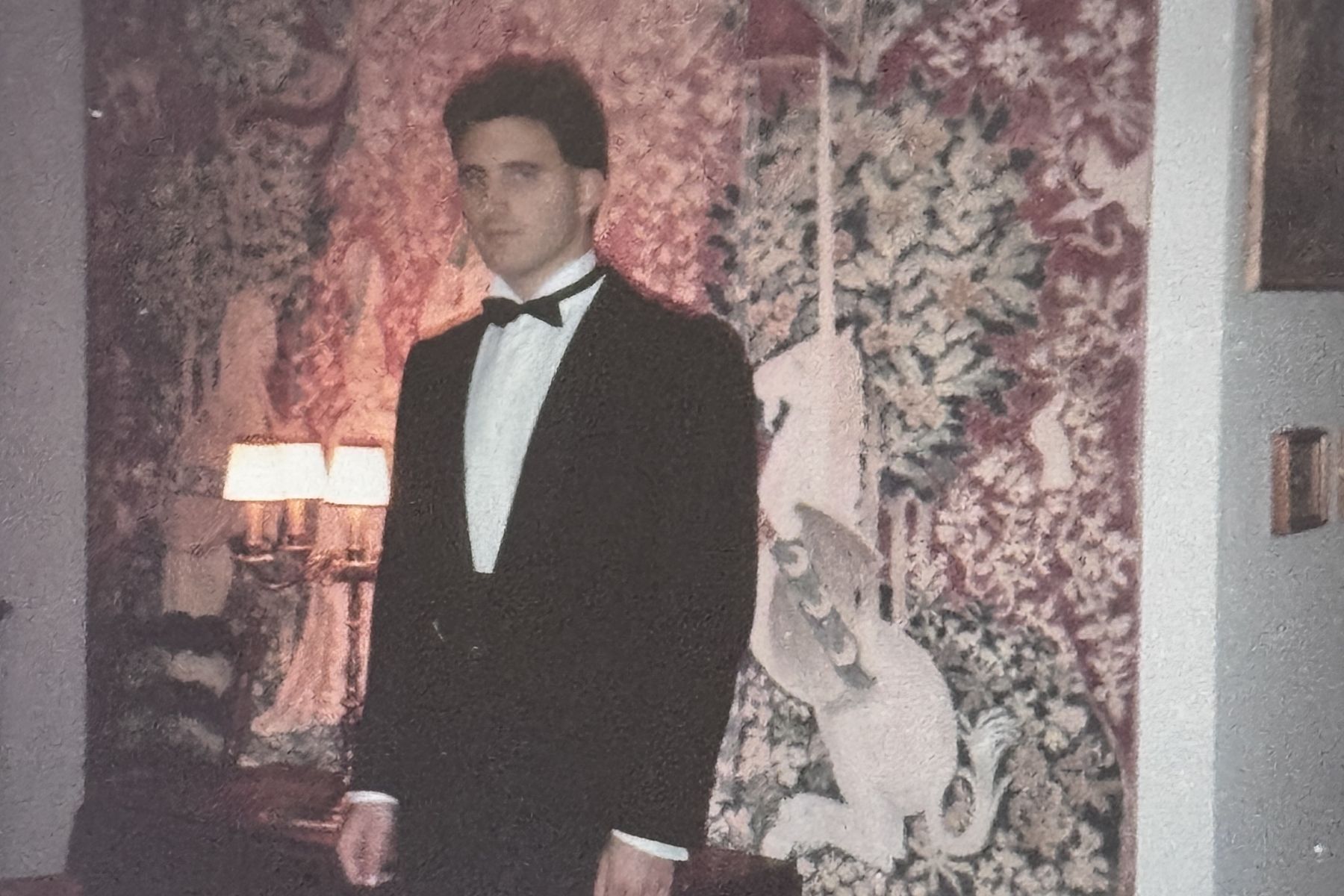

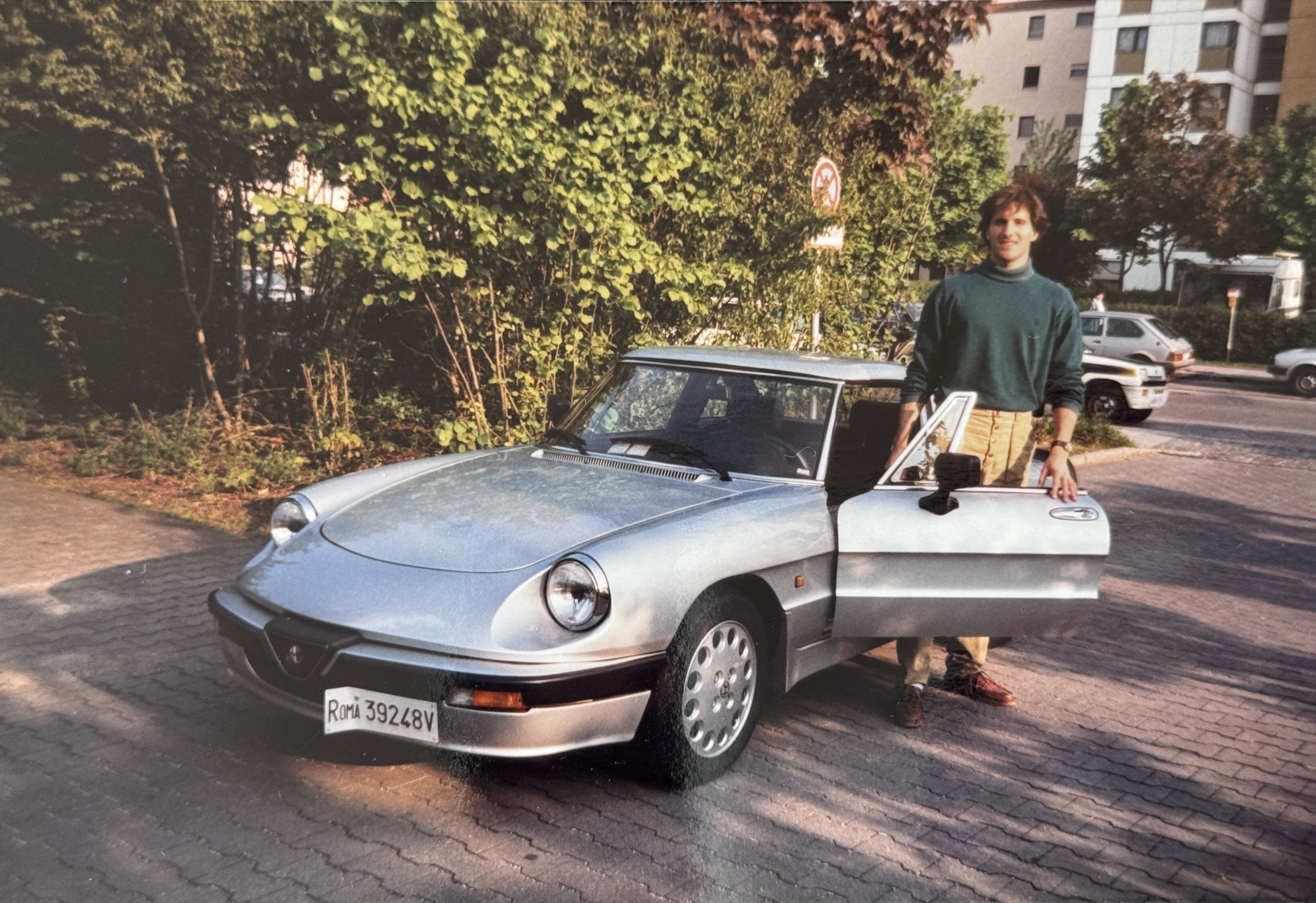

Zacconi during his consulting days in Munich, Germany, in the early 1990s.

“It’s important for a junior person to develop that toughness and assertiveness early on... The challenge is doing it without becoming arrogant — although in Riccardo’s case, because he is so kind and humble, that was never a risk.”

—Antonella Mei-Pochtler, former colleague at Boston Consulting Group

They worked on a six-month project assessing an investment and international expansion strategy for a leading Italian pasta company. The other partner on the project was “extremely tough on Riccardo,” Mei-Pochtler says, constantly pushing him for more data. She was happy with Zacconi’s work, but more impressed by his ability to navigate the differences in approach between the two partners, balancing the need for data on one side and a more holistic, strategic view on the other. She encouraged him to form his own views before following others, and to be assertive about what he wanted.

“It’s important for a junior person to develop that toughness and assertiveness early on,” she says. “The challenge is doing it without becoming arrogant — although in Riccardo’s case, because he is so kind and humble, that was never a risk.”

After six years at BCG, Zacconi left the firm to join one of its clients, a Swedish startup called Spray. It was there he met his future King co-founders, Sebastian Knutsson, Thomas Hartwig, Lars Markgren, and Patrik Stymne. The company, a web portal and Yahoo! competitor, had raised $100 million, a huge number for Europe at that time. In the span of a year, the company went from 20 to more than 800 employees, with Zacconi building a team of 100 as head of its German operations. The company planned to go public in March of 2000, but the dot-com bubble blew up those plans. The company was eventually sold to Lycos Europe, and Zacconi was offered an opportunity to stay on in a similar role. He declined the offer, but unlike many of his former colleagues, who went back to banking and consulting, he decided to stay in tech.

“I figured I had done the most expensive MBA in the world,” Zacconi says. “It would be stupid not to stay and leverage everything I had learned and all the people I met.”

"I could tell he was a natural leader."

—Mel Morris, uDate founder on Zacconi

In 2001, he received an offer to join Benchmark Capital as entrepreneur-in-residence in their London office. Before leaving Munich, he spent six months developing new business ideas, knowing that would be part of his mandate as EIR. One of his ideas focused on online dating, which he had begun exploring while at Spray. The web portal, which offered a search engine, news, and communities, also had a free dating site, one of the first in Europe. Zacconi discovered that in the U.S. Match.com had successfully monetized online dating, effectively improving its service by charging money and thereby qualifying the audience. Realizing there were no paid dating websites in Europe, he decided to pitch the opportunity to Benchmark, who agreed it had potential.

Their eventual target was a British dating platform called uDate. It had been founded in 1999 and quickly grew with a large presence in the U.K. and U.S.. Under the proposal, Benchmark would invest and put Zacconi in charge of building a presence in Europe. However, the business was already profitable, and they didn’t need the capital. The company’s founder, Mel Morris, turned down the offer and instead asked Zacconi to come work for him.

“I liked the approach he took,” Morris says. “He was very professional, a great listener. He asked loads of really searching questions. I could tell he was a natural leader.”

Recognizing that it was originally Zacconi’s idea, the Benchmark team encouraged him to accept the offer. He joined uDate as VP of Europe in August of 2002. He had partnerships lined up and a detailed strategy for global expansion. However, a few months later, the company was sold to Match.com. Zacconi made £350,000 in the sale — money that would be pivotal in the story of King — but again he was back to the drawing board.

A mighty quest

In March of 2003, Zacconi called up his former Spray colleagues and told them he had a new idea: competitive gaming. He saw similarities to online dating, in that games were a large market where most products were free. He proposed a new model where players paid to enter a tournament; the winner would receive 75% and the developer would take the rest. For the model to work, he said, the games would have to be skill-based — not random — and so fun they would practically market themselves. For that he needed a real product team.

Knutsson, Hartwig, Markgren, and Stymne were already working together, having founded a software development agency in Sweden. One of their projects was an app that allowed friends to prank call each other. They agreed to work on the project at a reduced rate, with Zacconi footing the bill alongside Toby Rowland, who had been an investor and VP of Marketing at uDate. However, within a few months of starting the new company, it became clear that they couldn’t succeed with the Swedish team working part-time. If they wanted to make it work, they needed everyone involved to be fully committed.

“That’s the difference between an entrepreneur and an investor,” Zacconi says. “An investor tries to hedge their bets, but an entrepreneur can’t. You have to go all in.”

Zacconi put in all £350,000 he had made while at uDate, sold most of his possessions, and moved into the small guest room of a friend, where he lived for the next two and a half years. Rowland, who came from a wealthy entrepreneurial family in England, matched Zacconi’s investment, and they bought the Swedish team out from their other partner. They called the new business Midasplayer, after King Midas, whose touch turned everything to gold.

Money, however, was hard to come by in 2003, and the team’s fundraising efforts fell short. Finally, Zacconi’s old boss at uDate, Mel Morris, agreed to provide the seed capital. Because the funds were controlled offshore by Morris’s trustees, the money didn’t arrive until the company’s bank accounts were practically zero. On Christmas Eve, only a few hours before Zacconi was set to fly home to Italy, he sat on the floor of their London office, staring at the fax machine, waiting for the trustees’ letter to come through. His heart leapt when the machine roared into action, but halfway through the signature page it made a strange noise and went silent. Zacconi took off running to find another fax machine, managing to borrow one from the building’s reception desk, and the funds arrived just in time.

Morris’s angel investment allowed the team to keep the lights on, and in January of 2024 they brought on board a second angel, Klaus Hommels. That funding allowed them to focus on product and sales. Leading product was Knutsson, King’s creative lead and the mastermind behind its most successful games. His ability to craft experiences that were fun and highly engaging, combined with his knack for balancing simplicity with challenge, made King’s games accessible to a global audience. Markgren, as CTO, and Hartwig and Stymne, the two best engineers from Spray, took charge of the front and back end of the games. With no budget for marketing, King adopted a B2B2C strategy, with Zacconi and Rowland traveling across Europe and the U.S. to establish partnerships with large portals like Yahoo! and T-Online.

Zacconi at an Index Ventures event in 2015.

The business became profitable in January of 2005, just a year and a half after launching their first game, and has remained profitable ever since. With some of those early profits, they made one of their first big marketing investments: purchasing the King.com domain for $200,000 from an American schoolteacher named Peter King, and rebranding the business as King.

In September of 2005, they decided to raise their first and last major funding round, a €33 million Series A from APAX and Index Ventures. Danny Rimer, a partner at Index, had met Zacconi when he was EIR at Benchmark, and they kept in touch over the years. After hearing Zacconi and Rowland’s vision for King, Rimer took what he calls an “unorthodox” approach: locking the founders in a room and telling them they couldn’t leave until they signed a term sheet. Zacconi and Rowland were “too savvy” for that, Rimer says with a laugh, but they appreciated his conviction. While APAX eventually led the round at a higher valuation than Index wanted to match, the King founders carved out space for Index, who agreed to acquire a smaller percentage of the company than they typically would in an early-stage round.

It was Riccardo’s sensibility, being both product-oriented and commercially-oriented... He had enormous respect for product and knew the company would be successful based on that. At the same time, he showed extreme confidence he could turn what they were building into a successful commercial venture.Danny Rimer,

Partner at Index Ventures

Index Ventures partner Danny Rimer (middle) with Zacconi in 2015.

“It was Riccardo’s sensibility, being both product-oriented and commercially-oriented,” Rimer says of the decision. “He had enormous respect for product and knew the company would be successful based on that. At the same time, he showed extreme confidence he could turn what they were building into a successful commercial venture.”

The road to success, however, was much longer and more challenging than either Zacconi or Rimer anticipated. To get there, the entire King team would need to navigate muddy waters, adapt to a rapidly changing market, and stay true to their vision.

Storming the castle

By 2007, King had around 100 employees, revenues of $60 million, and partnerships with most of the large portals in the U.S. and Europe. But trouble loomed with the passing of the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006, which targeted online gambling companies in the U.S. Although King’s games were purely skill-based with no element of chance, they still involved money, as players paid entry fees to compete for cash prizes.

Zacconi received a letter from Visa in 2007 informing him they would soon stop processing payments for King’s games — a decision that would wipe out 50% of the company’s revenue and almost certainly lead to its collapse. Zacconi calls it their first “near-death moment” since that fateful Christmas of 2003. With the support of APAX, Zacconi hired top lawyers and after lengthy negotiations managed to strike a deal with the credit card processing banks to keep Visa on board. King’s demise was averted — at least for the moment.

Next came the rise of Facebook. Launched a few years earlier, the social media startup opened its platform to partners in 2007, and the first Facebook gaming companies, led by Zynga, began to emerge. At the time, King was the highest-grossing company on Yahoo! Games. Zacconi approached Facebook’s management, hoping to bring King’s model to their platform. Despite reassurances about their legal position, Facebook refused, fearing the games could be seen as gambling. King had to find another way to break into Facebook.

“Right now, things are good. We have loyal customers, we’re profitable... We need to crack Facebook.”

—Riccardo Zacconi

They carved out a small team led by Alex Norstrom (now Co-President of Spotify) focused entirely on cracking Facebook. Meanwhile, Facebook’s user growth accelerated in 2009, just as King was in negotiations to be acquired by Electronic Arts (EA). Those discussions had started in late 2008, when Zacconi and Rimer met with EA’s then-CEO, John Riccitiello. However, as users flocked from portals like Yahoo! to Facebook, embracing hit games like FarmVille and Mafia Wars, King began losing users at an alarming rate. By the end of 2009, King’s user base had dropped by 45%, and talks with EA fell apart. Zacconi calls the next two and a half years one of the hardest periods of his life. While fighting to keep up team morale and retain talent on one side, and managing pressure from investors on the other, he and his co-founders tried to chart a course that would allow the business to survive and grow again.

Finally, he called a company-wide meeting to make clear to everyone the situation they were in. He showed an illustration by the Argentine cartoonist Mordillo that depicted two lovers sitting on the sand under a beach umbrella in the shining sun. “Right now, things are good,” he told the team. “We have loyal customers, we’re profitable.” As he zoomed out, however, he revealed that the sand in Mordillo’s cartoon was the top half of an hourglass. “It’s only a matter of time,” he said. “We need to crack Facebook.”

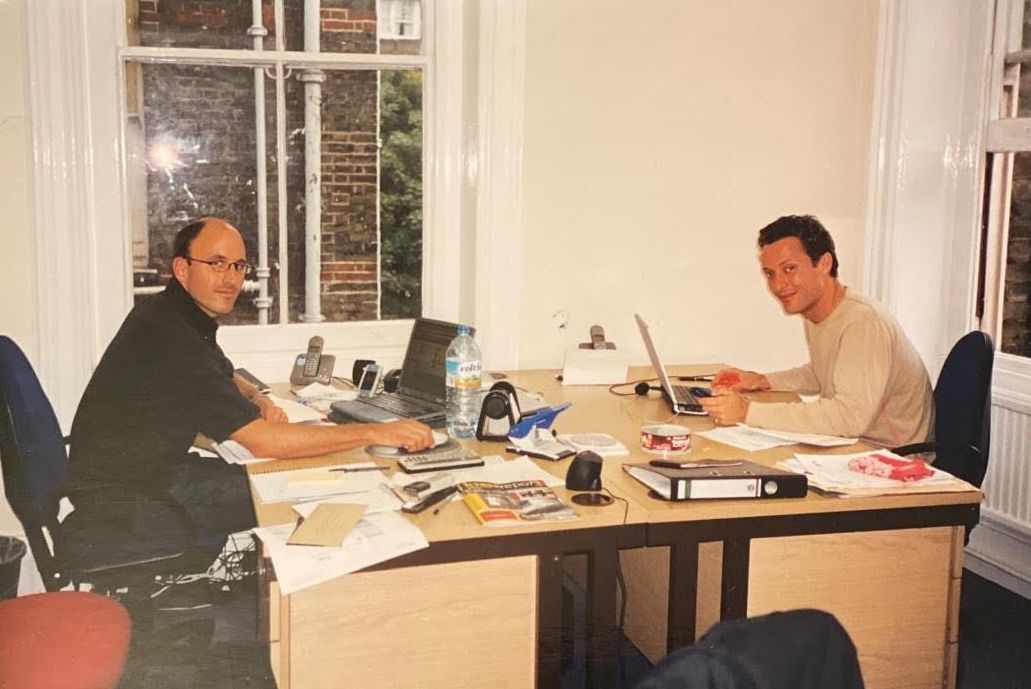

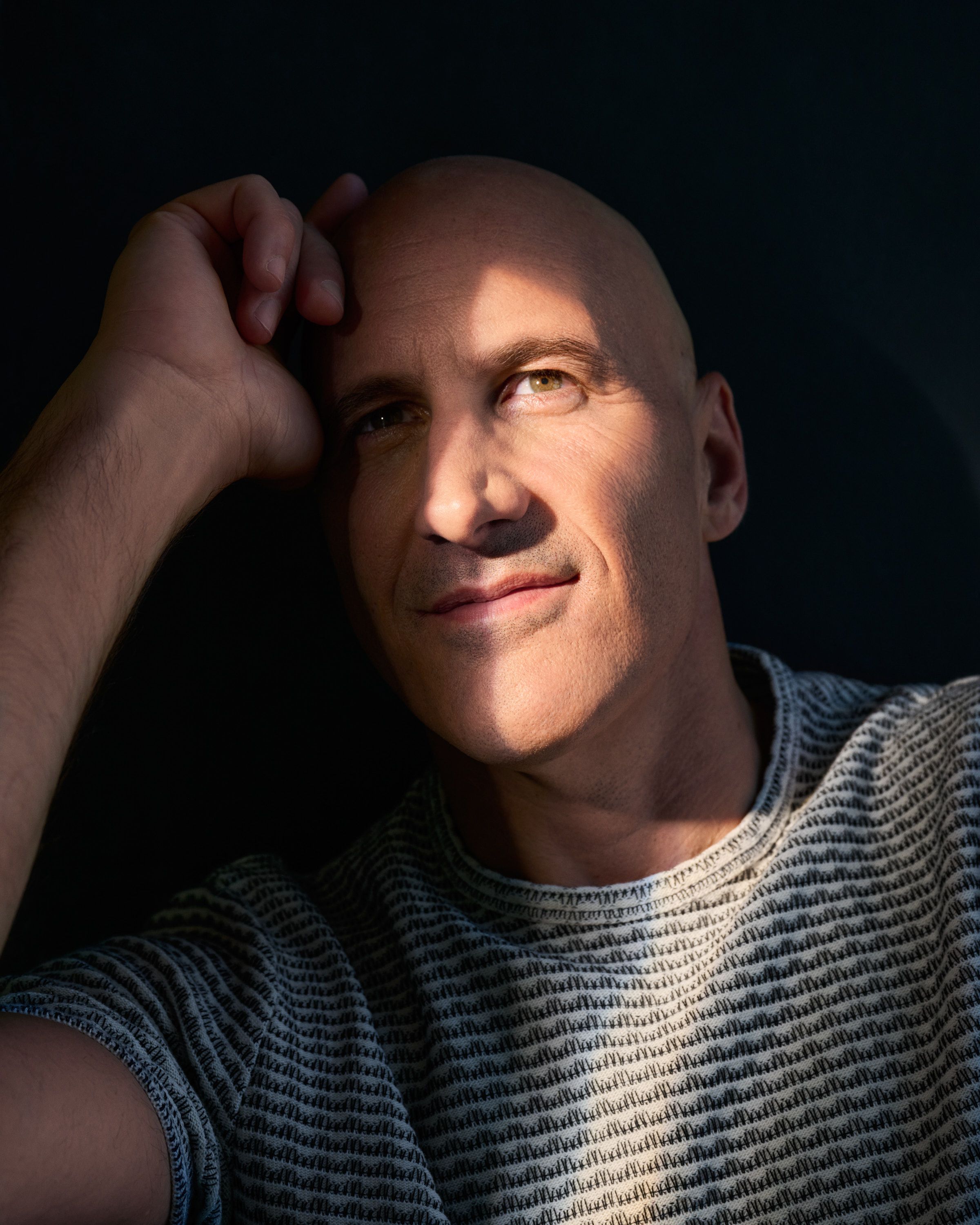

King co-founder Riccardo Zacconi.

He announced a radical restructuring: King’s 110 team members would be split into two groups. One half would be responsible for maintaining the existing business. The other half would be divided into five teams working on five new concepts designed to crack Facebook. Each group would have to be laser-focused, working with minimal resources. Knutsson would oversee the product teams focusing on Facebook and no longer work on the existing business.

The reorganization also affected marketing. Until that point, King had grown its core business via partnerships. While they had a direct-to-consumer offering on King.com, the 20-person marketing team in Hamburg was effectively a sales team. Zacconi made the “necessary but painful” decision to fire the entire Hamburg team and hire a new performance marketing team in London, led by Angus Lovitt. This was especially difficult, Zacconi says, because the COO who had hired the Hamburg team was also a friend. The COO resigned, and in 2011 Zacconi brought in Stephane Kurgan (now a Venture Partner at Index Ventures) as King’s new COO.

After years of hard work with Knutsson at the creative controls, the breakthrough finally came in March of 2011, when one of the team’s Facebook experiments, Bubble Saga, started to gain traction. The game was a reworked version of a previous competitive game King had launched, and while it didn’t generate significant revenue, it showed outstanding retention metrics. “This was the turning point,” Zacconi says. “We realized we could leverage our 200-plus existing games and reformat them into non-competitive versions for Facebook.”

From there, they turned their focus to monetization, launching a freemium model where players would provide value either by paying or generating viral leads. The first game with the new model was Bubble Witch Saga, launched in September of 2011. Its retention and monetization outperformed expectations, allowing King to once again scale their marketing.

The “dark years” behind them, King entered what Zacconi calls “phase one” of their growth on Facebook. Having cracked the formula for adapting their existing portfolio of games for the social platform, King’s tech team, led by Hartwig, began developing a platform to standardize common game components, enabling faster and more efficient deployment of new titles. Kurgan, a veteran of the B2B world, embraced the strategy, creating organizational processes to support fast growth. Under his leadership, King overhauled its hiring process to ensure quality while scaling. Every new hire underwent six interviews, including three with departments other than the one they were joining. Zacconi and Kurgan personally interviewed all senior hires. King grew to 300 employees in one year, opening new offices to expand their talent pool.

“When you trust people and you treat them like adults, amazing things can happen.”

—Riccardo Zacconi, co-founder of King

With this new infrastructure, King scaled its marketing investment, becoming the second-largest gaming company on Facebook. However, Zynga, the dominant player, owned 85% of the market and released their own versions of King’s most popular games, causing King’s reach to again slide. This prompted King’s second phase of growth on Facebook: mobile games.

Although the company had been experimenting on mobile since the launch of the iPhone in 2007, it took five years before the company broke through. Zacconi credits the early 2012 acquisition of Resolution Games, a small mobile game developer, as being “instrumental” to King’s success on mobile. He specifically highlights the contributions of Resolution’s founders, Tommy Palm and Alexander Ekvall, in bringing Candy Crush Saga to mobile.

Another innovation that fueled King’s mobile success was the release of their first multi-platform game, Bubble Witch Saga. It allowed users to switch between PC and mobile without losing their progress, while playing with friends across any platform. This meant King could leverage the large user base they had already built on PC when launching games on mobile.

Candy Crush Saga launched on PC in June of 2012, and while the game performed well, its true explosion came with the mobile release in November of the same year. Despite missing out on a planned feature spot in Apple’s App Store, the game quickly climbed the ranks, driven by King’s existing user base. Zacconi notes that the lack of early promotion actually helped King by providing cleaner data on the effects of virality and marketing campaigns. King began scaling its marketing, growing from a modest budget to over $100 million per quarter in 2013.

It’s very rare in business to find people with the combination that he has. He’s a visionary. He’s unbelievably charismatic. But the thing that struck me in that first meeting, and every interaction we’ve had over the years, is he’s a man of extraordinary empathy. He can very quickly see and understand who people are, what keeps them excited. And he has a very unusual skill in being able to not just identify those things, but then have a real connection and empathy for what drives people at an individual level.Bobby Kotick,

CEO of Activision Blizzard from 1991 to 2023

By 2013, King had conquered Facebook, with nearly half a billion monthly players, and revenues soaring from $62 million in 2011 to nearly $2 billion. Zacconi says credit is owed to those around him: “For me, it’s all about bringing on board people who are better than me and letting them do what they’re best at. It’s because of them that we succeeded.”

King’s culture, he adds, was another key ingredient in King’s survival and success: flat hierarchies, openness and transparency, treating people with respect, and being willing to take risks and learn from mistakes.

“The most important thing of all was to not tell beautiful lies,” Zacconi says. “When you trust people and you treat them like adults, amazing things can happen.”

Riccardo Zacconi, co-founder of King.

King’s legacy

Bobby Kotick knows a thing or two about joy. The CEO of Activision Blizzard from 1991 to 2023, Kotick also spent 10 years on the board of The Coca-Cola Company. In the same way the soft drink giant delivers “moments of happiness,” Kotick says that King’s games — and Zacconi’s legacy as an entrepreneur — have brought joy to millions of people around the world.

“In 30 minutes of playing Candy Crush, you’ll be rejuvenated and refreshed,” Kotick says. “That was always the underlying principle behind Riccardo and the team’s work at King — allowing people to experience joy and fun and take their mind off of life’s challenges.”

Kotick met Zacconi in 2012, when Activision Blizzard was thinking about how to develop its mobile gaming strategy, and Zacconi and Kurgan visited the company’s offices in Santa Monica. Kotick admits that going into the meeting he hadn’t been particularly interested in hearing from two “management consultants,” but as Zacconi and Kurgan outlined their vision, he could tell “these were extraordinary guys.” The timing wasn’t right for a deal, and two years later King went public. In 2016, however, Activision Blizzard completed its acquisition of King for $5.9 billion. While the wild popularity of King’s mobile games didn’t hurt, Kotick says it was the company’s executive team, and in particular Zacconi’s leadership, that convinced him to do the deal.

“It’s very rare in business to find people with the combination that he has,” Kotick says of Zacconi. “He’s a visionary. He’s unbelievably charismatic. But the thing that struck me in that first meeting, and every interaction we’ve had over the years, is he’s a man of extraordinary empathy. He can very quickly see and understand who people are, what keeps them excited. And he has a very unusual skill in being able to not just identify those things, but then have a real connection and empathy for what drives people at an individual level.”

Kotick credits Zacconi with building a diverse and inclusive culture at King, long before DEI became a common mandate. “He understood that if you’re creating content for hundreds of millions of people in 190 countries, 70% of whom are female, you need to have different skills, talents, and backgrounds,” Kotick says. For Zacconi, not only was it about building a welcoming culture and ensuring a diversity of perspectives, he says “selfishly” he wanted to find the best talent, and the only way to do that was to expand their pipeline.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re black, white, male, female, non-binary — a smart person is a smart person,” he says. “If we see a particular group is underrepresented, that means we have a percentage of smart people who haven’t joined, and we need to look harder.”

Zacconi defines culture as the way employees behave in a company. That means everything from what time you come into the office and whether you clean up after yourself, to how you’re expected to treat others and whether you’re allowed to take risks. Culture is a pyramid, he says, with leadership creating it from the top. “When you get into a company and try to understand the rules, you don’t read a document,” he says. “You look up and see how others are behaving.” If another leader isn’t modeling the behavior he wants to set for others, it doesn’t matter how talented they are. The culture must be protected, even if it means firing them (“always fairly,” he adds). Otherwise you risk their influence spreading to others.

As for what Zacconi believes, he says he tries to keep it simple. Treat others as you would like to be treated. Transparency and honesty are key. There is no truth until you test. Strategy is where it starts. Don’t be afraid to take risks. If it doesn’t go well, simply try again.

Mel Morris, chairman of King from 2003 to 2014, saw these values in Zacconi as far back as their earliest conversations at Benchmark and uDate. He says that over the years, even during the most difficult times — getting King off the ground, trying to crack Facebook — Zacconi never lost sight of his values. “He was always thoughtful, full of integrity,” Morris says.

In 2008, a particularly stressful time for Zacconi while the company's leadership structure was in flux, Morris invited him to come down to his house in Spain. Morris owned a “ridiculously fast” Jet Ski, and he said to Zacconi, “Let’s go out in the water and park it up and have a chat.” They were three or four miles offshore, in the middle of a conversation, when Zacconi tapped Morris’s shoulder and said, “Mind if I swim back?” Morris couldn’t believe it. He said, “Are you kidding? We can barely see the coastline.” Zacconi jumped off and began swimming, while Morris circled at a distance. Two hours later, Zacconi reached the shore, hopped out of the water, and picked up the conversation right where they had left off.

“Someone who can do that has got to have a certain level of fortitude and confidence and lack of fear,” Morris says. “It showed the character we had in this leader. He didn’t think twice about it. He knew what he was capable of. To Riccardo it wasn’t a risk at all.”

Published — Nov. 19, 2024

-

-