Culture Matters

Why building a distinctive and durable company culture is as vital for attracting and retaining talent, as it is for building resilience for turbulent times.

From rooftop meetings to hammock-strewn breakout areas, and free yoga classes to catered Friday lunches, the visible trappings and perks of tech company culture have become the stuff of industry cliché, ubiquitous in offices from the Bay Area to Barcelona and lampooned in shows like HBO’s Silicon Valley. However, the underlying qualities which mix together to help a company develop a distinctive and, crucially, durable culture are far harder to pin down, as is the way founders successfully cleave to those values, as their company grows from perhaps a handful of people in a co-working space to many hundreds scattered around the world.

Few people have a better grasp on all of the above than Didier Elzinga, CEO and cofounder of Culture Amp, which is building the world’s leading survey platform for people and company culture. “What we've seen over the years is that the companies that do it best, think about culture very much like they do about brand,” he says. “I like to say if brand is the promise to a customer, then culture is how you deliver on that promise. The companies that have done it well are those that have sat down and intentionally described the experience they want their people to have and then measure it to see what’s actually happening.

Index Conversations on Company Culture. Ludwig Siegele from the Economist moderates a discussion with Sian Keane, VP of Talent & People at Farfetch, Nicole Vanderbilt, VP of International at Etsy and Nilan Peiris, VP of Growth at TransferWise

“It's not just a case of them saying ‘Here are our values, and here’s what we want to be’, it's also asking - as the leaders in an organisation – how, for example, management works in your company?” Elzinga continues. “What should your people expect from their manager? Are they coached or driven? Or when somebody joins the company how should they feel on day one? How should they feel at the end of their first week? Or at the end of their first month? And it’s not letting that be something that just happens by chance, but something that's intentionally driven.”

Elzinga describes this approach as ‘culture by design’, and it’s a theme Culture Amp - which has worked with over 700 companies, across a range of industries - explores with reference to tech companies, across the growth spectrum from seed to exit/IPO, in its report. ‘The Culture Crunch: The challenges technology companies face through growth’ has gathered data from 71,000 respondents in 187 tech companies to track their engagement – defined as “a measurement of the level of connection, motivation and commitment a person feels for the place they work”. Among the findings in the data, the report describes the “wide variance between how companies at different stages are engaging their employees.” It goes on to state, however, that “a clear pattern emerges, with earlier stage companies generally having more engaged people than later stage companies”.

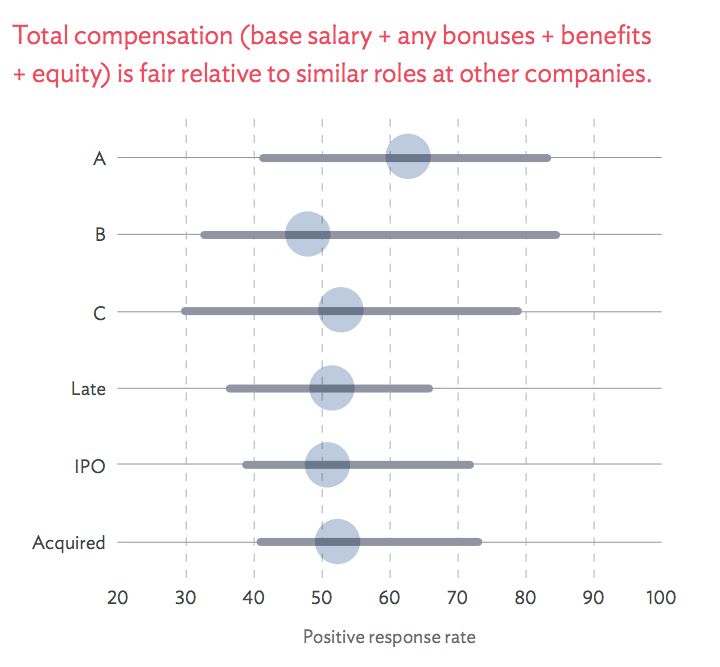

As companies move through the various phases of growth, the ‘pain points’ they encounter shift too. The report found, perhaps surprisingly, widespread satisfaction with compensation among early stage company employees – perhaps because startups tend to offer more equity, along with a shared sense of mission. Early stage companies also scored highly across inter-departmental collaboration and innovation. “As early stage companies generally tend to be smaller, we hypothesize that the processes within them allow people to get things done, meaning people are more engaged in their work, with a unified goal, and with fewer blockers…” the report continues. “People who work at early stage companies are highly engaged and value efficiency, constant improvement, and innovation.”

However, there was evidence that the transition from Series A to B can often be turbulent -- not least over whether employees could imagine staying at the company in the short-to-medium term (Series B companies scored -7.2% below the median when asked whether they could see themselves working at the company in two years time.) Similarly, Series B companies also scored lower on questions such as whether employees felt their job performance is evaluated fairly, whether they receive useful feedback and on whether the information they need to do their job effectively is readily available.

The band indicates where 95% of scores fall. The large dot represents the median score of all companies within each funding series.

The report cautions that managers are frequently tasked with smoothing and navigating the transition of existing staff into more focused roles. “Communication and careful planning are keys to keeping the workforce engaged,” it continues, going on to advise leaders not to try to fix every single issue. “It may be helpful to spend time managing perceptions and expectations, rather than treating the symptoms here, as many of these factors are a natural consequence of growth.”

By Series C stage, employee engagement is at its lowest ebb, with companies “rife with inefficiency and confidence issues carrying over from more rigid structure”. The report notes that “companies at this stage seem to be suffering from the internal perception of losing the innovative practices of earlier stages”, adding that because Series C is a period “where companies look to massively scale, be acquired or discover new markets, it might be the case that leadership often struggles to keep their people in the loop”. To mitigate this, the authors suggest that “transparency and communication, though important at all forms of an organization’, might be the most important things to stay on top of at this stage”.

Post-Series C is often the period of peak company confidence. Conviction that the company “is in a position to succeed over the next three years”, that it “effectively directs resources towards company goals”, while day-to-day decision-making demonstrates “that quality and improvement are top priorities”, are all statements that a higher percentage of respondents than the report’s median agree with.

Yet, notes The Culture Crunch, success can come at a price for employee engagement. “…As future events such as IPOs become imminent, this can cause significant disruption and distractions for employees. Companies approaching IPOs may double down on sales, user numbers or other hard KPI type metrics that are deemed crucial for valuations for example. This can lead to employees in functions less related to these metrics feeling neglected or disillusioned.” The report suggests focusing on “communicating some of the realities of the situation, [finding ways to] alleviate some of this, and a vision for the future that clearly articulates how those potentially neglected employees will benefit (not just monetarily).” The Culture Amp team also recommend prioritising hires who are passionate about the company to motivate staff.

The talent pain-points shift again for exited companies. Due to their comparative scale, post-IPO companies can leave staff feeling “unable to make a difference, innovate or be effective – [which are all] key driving factors at early stage companies. Post-IPO, the product’s locked in place and organizational design appears to be set and a key metric for performance is invariably tied to stock price. This makes for a tricky situation.” To counter this sense of ennui among employees, companies can “look to play to their [people’s] strengths and find ways [they] can contribute more often to the company”.

Meanwhile, acquired companies have the lowest level of engagement across all stage groups, largely because of the uncertainty acquisitions can breed, according to the report’s data. Not only do staff tend to be anxious about the company’s immediate short-term future, but they worry about career opportunities and feel less motivated as a result. As career perceptions are crucial for retaining people, The Culture Crunch suggests acquired companies “ensure that career conversations occur as soon as possible with all individuals in the acquired company.” Clear guidelines for managers to hold such discussions should be in place, and sufficient time allocated for managers to spend direct time with new employees.

“Engaged employees are likely to be more productive, creative and innovative”, concludes the report. Elzinga adds that they are also likely to have an “emotional commitment to the organization and its goals”, which can prove critical to a company’s success. “One of the ways I think about engagement is through the ‘5 o’clock test’,” he says. “The phone rings and somebody's about to walk out of the office -- do they answer the call or not? If they care about the company they will; if they don't care about the company they won't. That's up to you, as a company, to create a place where people care, so that it’s not just about their commitment when they are clocked in, but do you have all that they can bring to your organization?”

Brad Bird said that if you have low morale as a company, for every dollar you spend you get about 25c of value. If you have high morale, for every dollar you spend you get about $3 of value.

To reinforce the point, he quotes from film-maker Brad Bird, director of The Incredibles, among other classics. “Brad Bird said that if you have low morale as a company, for every dollar you spend you get about 25c of value. If you have high morale, for every dollar you spend you get about $3 of value. That’s why companies should pay more attention to morale. I love that because it just captures the whole idea so powerfully: if you have engaged people, the money you put into your company will go so much further.”

But what makes people engaged in the first place? And how to define company culture, beyond the slogans and taglines that some businesses like to hide behind? For Index Ventures co-founder and partner Neil Rimer, when it works well, culture isn’t something that people in an organization have to think about; rather it’s a collection of values which kick-in instinctively as situations and moments of decision-making arise:

In great companies, whether it’s two people or 200, you find complete consistency and coherence in what two different people will tell you about a company, about a specific challenge or opportunity that it's facing,” he says. “And that's not because they spend every day rehearsing that answer, it's because the company’s leadership has been able to distil that into a set of values and principles that they've shared with everybody in the company and that those people have embraced.

Rimer goes on to explain that it was its uniquely creative culture-by-design that drew the Index team to the Helsinki-based mobile gaming company Supercell, makers of Hay Day and Clash of Clans, in which the firm invested in 2013. “With Supercell, it was all about culture. What makes that company so special was the culture that it created that allowed it to attract and motivate super creative people, and enable them to come up with an unprecedented number of top five games.

“But the reason we invested in that company wasn’t because of the games they had on the market, it was because of the culture that had lead to the creation of those games, and the fact that they had started from first principles in thinking about the culture they wanted to have. Their organizational design came to define Supercell, because of the way it would have small teams, called ‘cells’, which would be able to come up with their own games and take them quite far. That was unique versus a typical studio culture, where you have big studios working on lots of different things, with teams in lots of different places (because you needed to chase talent and talent wasn't all in one place). They took a completely different approach and said if you want to work for Supercell, you have to come to Helsinki.”

How important does Rimer think it is for companies to write down such core values and in effect, codify their culture, particularly as they start to grow? “The most important thing is they think about it and they're aware of it and they do this deliberately and explicitly, and don’t assume that it will just happen because they are working on something interesting or vital,” he replies. “Culture’s something that requires somebody's real attention. Not just to encapsulate it, but also to nurture it and promote it. If the culture is being challenged or stymied by changes in the business or to the team, something needs to be done about that.

“There are companies where – and at Index, we don't really gravitate to those companies -- they don't really pay any attention to this kind of thing. They are fewer and further between now, because I think people have understood how important this is. But it's not the kind of thing you can just slap on like a tagline or a logo. Or go get somebody to do it for you. This has to come from the guts of the company and often the leadership. And whether they write it down or not is less important. In the early days, if there are three people saying it out loud, that’s just as good. But as the company scales, clearly it will have to be codified and shared in written or other forms for it to survive,” he says.

One leading company that has ‘codified’ the core values which underpin its mission, as it scaled, is Funding Circle, the world’s largest marketplace exclusively focused on small businesses. “They are: ‘Think Smart’, ‘Make it happen’, ‘Be Open’, ‘Stand Together’ and ‘Live the Adventure’,” says cofounder Andrew Mullinger, listing them. “When you start out, it’s basically the behaviours and how the founders and the original employees treat each other which define the culture. But when you get to some scale, you need at least an articulation of what the values of the company are.”

Andrew Mullinger, co-founder of Funding Circle in discussion with Index partner Neil Rimer. "Values and slogans are all well and good, but as a company you don’t really know how robust your culture is until you hit rough terrain and what you stand for is put to the test," said Mullinger.

However, continues Mullinger, values and slogans are all well and good, but as a company you don’t really know how robust your culture is until you hit rough terrain and what you stand for is put to the test. “Often a successful culture for a business will be one that’s supportive, and where you all play for the greater good and there’s an element of selflessness about it all. That sort of culture is strong enough to deal with people who are performing poorly.” But if there are flaws and negative traits, they will rise to the surface at moments of crisis, he explains. “If you have a business where people are secretive, or you have a very aggressive sales culture, or your company’s very hierarchical, or whatever it is, the danger is it can work for a short time, but as soon as problems happen and difficult times come, that same hierarchical culture, for example, leads to bad communication and office politics. And when that happens, everything can quickly start to fall apart.”

While it’s relatively easy to define company culture when you’re a startup – after all, there are just a few of you, united by a vision and embarking on a shared journey -- it becomes exponentially harder as a company grows, as well as even more integral to your success. “It's not just the expression, it’s the DNA that encodes the expression of the values,” says Rimer. “And it only works if it’s self-perpetuating. Probably one of the greatest leverage points of a culture is that it influences - and confirms - hiring decisions. Those hiring decisions will favour people who fit the culture, and also embrace it and propagate it in the people they work with and the hires that they make.”

So how does a culture become self-perpetuating, and how do you retain the same sense of purpose and identity, when you require an aircraft hangar for your end-of-year party, and ‘all hands’ meetings require dial-ins from offices around the world? One Index-backed company which knows all about such growing pains is Etsy, the marketplace where millions of people around the world connect, both online and offline, to make, sell and buy unique goods. It has 921 staff members, in offices stretching from its headquarters in DUMBO, Brooklyn, to Melbourne and Tokyo.

Nicole Vanderbilt, Etsy’s London-based VP, International, says there are two factors which have helped the company maintain its culture as it has scaled. “Even at the earliest stages of a company’s development, the most important thing in establishing a strong culture, is the leadership team constantly demonstrating those values through their own behaviours. I firmly believe that nothing replaces that. No amount of posters on the wall or policies can replace that.”

For Vanderbilt, this manifested itself most clearly during her pregnancy. “At the time, I was reporting to Chad [Dickerson], our CEO, and many times during that period he gave me examples of where he and others in the company were supporting parents in everything that they needed to be both effective workers and parents. He told me a story about our old CTO bringing his young daughter to a meeting because he had a childcare crisis. He made it clear that he felt that was a totally reasonable thing to do. He also demonstrated this, himself, as a parent, when he missed one of our team meetings because he went to volunteer at his child's school one morning. It’s seeing your values and culture in action in the behaviours of your leaders that matters.

“I've worked at companies where people and policies say that. But, when it comes down to it you’ve never seen your boss leave to go to his or her child's recital, or, worse, you’ve seen other people cringe or look down on someone who does do that. Seeing those behaviours demonstrated so clearly by the Etsy leadership team really reinforces our culture in a way that no handbook alone would ever be able to.”

Vanderbilt’s second point stresses the importance of continuing to protect the company’s values, as it expands. “Things that you've taken for granted as implicit, you need to make more explicit and spell out,” she says. “One example at Etsy is that we have a fairly standard interview evaluation form to fill out for new hires. This form used to include a question about their “Etsyness” (which was kind of code for alignment with our culture). In the early days, it was a bit more obvious what we meant by that, and everyone was fairly aligned. But as we grew, it started to wander. Did this mean that they know how to knit? Or that they like to code? Or that they are vegetarians? In absence of clarity, each person started to assign their own, and often slightly different, attributes to it.

"Things that you've taken for granted as implicit, you need to make more explicit and spell out."

“One of the things the HR team have done did in the last year or so has been to take a step back and say ‘OK, let's put some more definition around this. Let’s give people more of a guide and some tools and questions that they can use to help us get better answers and better data’. It’s a great example of where something that feels informal, obvious and implicit early on, benefits from being more codified and explicit as you grow.”

Also key to a company retaining its cultural DNA, is accepting that it will gradually evolve, as extra layers of management and offices around the world are added, argues Leah Sutton, head of HR at Elastic, an Index-backed company which provides software products to enable developers, startups and enterprises to make complex structured and unstructured data usable. “People tend to say ‘our culture is this’. But culture is also dynamic, and over time it shifts, which is why it’s important to identify the core components you don’t want to lose - the things that got you to where you are - as you get bigger and get more structure, processes and people, who aren’t necessarily as bought into that initial idea.”

One of the first things Sutton was tasked with upon joining Elastic was re-evaluating the company’s on-boarding process. “It’s easy when you’re growing really fast just to chuck new hires in and let them get cracking, without any ramp-up in terms of who we are and what are values are,” she says. “One of the things we do at Elastic is ‘X School’, and all our new hires come in for a week of pretty intensive induction, where they hear from all the different function leaders, learn a little bit about our business and products and, frankly, just spend time with the team. In our case, because we're so highly distributed, it makes it even harder [to retain a company culture], because we have people working in 34 countries -- we do have offices, but the majority of our people are not in a shared physical space – so creating those connections whenever and wherever you can is really important.”

While maintaining a strong and authentic culture is essential for all great companies, striving for ideological perfection is rather less so. As a company grows, cultural purity becomes harder to pull off, which is no bad thing, says Funding Circle’s Mullinger. “It's a lot easier when you are sub-100 or 150 people [to be pure]. Once you get bigger and bigger, the nature of it is that there will always be a slight level of hypocrisy around what you stand for as a company because life unfortunately is like that – messy. But the good people that you have will understand that that's the nature of growing a large business, and as long as they see you are getting eight out of ten things right, then usually they are very pleased.”

For his part, Culture Amp’s Elzinga agrees. “You're never going to get it perfect, particularly in large companies,” he says. “As we like to say, there is no such thing as a perfect culture -- that's known as a cult.”

Posted on 13 Sep 2017

Published — Sept. 13, 2017

-

-