Copenhagen Rising

Istedgade in Vesterbro, Copenhagen

Tine Thygesen, founder of Founders House

Founders Reception in Copenhagen, hosted by Index

Back in 2008, Tine Thygesen, a serial entrepreneur, returned to Denmark after stints in Australia and the UK. There was very little by way of a startup community in Copenhagen then, she recalls, and if you said you were an ‘entrepreneur’ you’d be met with a knowing smile. “Most people thought it was a fancy way of saying ‘I can’t get a job’,” she laughs.

After running Venture Cup, Denmark’s largest initiative for university startups, Thygesen founded Everplaces, a mobile technology company, and began casting around for office space. “In those days startups had a choice between these vast, cold science parks, where no one spoke to each other, or government-supported shared offices, where you’d be sitting next to companies which were totally unrelated to you – one of the startups we knew sat next to a dentist.”

Thygesen went on to co-found Founders House, Copenhagen’s first tech startup co-working space. "We had two conditions for any founders joining us,” she says. “They had to be all-in -- they couldn’t be working on their startup part-time – and their idea had to be scalable."

Founders House, now comprising some 35 companies, is based in Njalsgade, the fashionable warehouse district of Islands Brygge, and is part of one of the largest concentrations of tech startups in Northern Europe – 14,000 square metres of building space, housing some 50 companies consisting of 500 people collectively known as Startup Village.

Founders House in Copenhagen, home to some 35 companies.

With 300 to 400 tech companies in the Oresund region, Copenhagen’s startup scene has reached escape velocity over the past few years. “We don’t know the exact number [of startups], because it depends how you define them, but it’s by orders of magnitude better than it was,” says Karsten Deppert, a company founder who runs the website Oresund Startups in his spare time. “The ecosystem’s growing, there are now lots of coworking spaces, meetups and more people involved in the scene in general – all of those things, provide the ground for more startups to grow.”

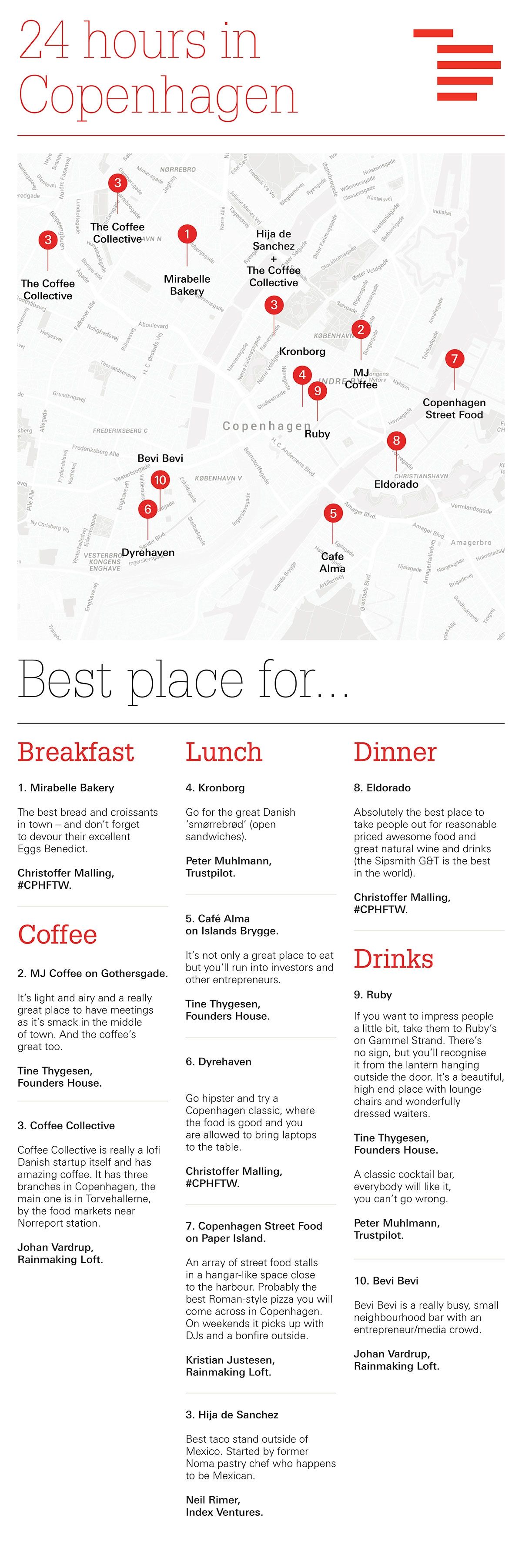

‘Copenhagen, for the Win’, a grassroot non-profit initiative better known by its hashtag #CPHFTW is frequently credited for galvanising a good portion of that growth. Describing itself as “by startups, for startups”, #CPHFTW came about after a group of about 70 people from across the Danish startup scene – comprising founders, angels, students and others – coalesced around a shared analysis, namely, that while things were steadily improving in Denmark, the country’s tech ecosystem was still losing ground to Sweden, Finland and other high flying tech hubs across Europe.

“We knew we were lacking something the others have and it was time to remedy it,” recalls Christoffer H. Malling, head of #CPHFTW. “We then went out and held our first town hall meeting, where 300 people were invited, and we asked them if they would sign on for this idea – and everyone was ready. In late, 2014, we raised around €100,000, and with this money we were able to go beyond being a voluntary organisation.”

As #CPHFTW ramped up, regular packed-out town hall meetings were followed by investor-focused events, where startups would pitch to a roomful of angels or local VCs. “Then we started inviting international VCs, like Index, and matching them up with startups. That helped give those VCs a foothold in Copenhagen, and we’d liaise with them further on down the line.”

Overall deal flow in Denmark has spiked dramatically since 2014. According to figures from The Nordic Web, in 2014, 38 investments were made in the country’s startups, worth $205.4m, rising to 65 (worth $273.5m) last year. So far, in Q1 2016, the website has recorded 29 Danish investments totalling $91.77m. (The Nordic Web’s editor Neil Murray reckons more than 90% of these investments took place in Copenhagen.) So how to account for Copenhagen’s almost below-the-radar success?

Cultural Beacon.

Index Ventures partner Ben Holmes -- whose investments in the country include Copenhagen-born international takeaway service Just Eat and Trustpilot, Europe’s largest consumer review platform -- thinks there are three compelling reasons. The first is that a number of successful large businesses and headline-grabbing exits have now emerged from what he describes as a thriving local ecosystem. “Index has been lucky to be involved with a few of these, including Zendesk, Milestone Systems, Trustpilot and Just Eat,” he says. “Stockholm has had a few big successes, and London too, but now Copenhagen has got quite a few on the map as well.”

Second, he points to the fact that Denmark, generally, has become, despite its size, “a cultural beacon”, about which the world is increasingly aware, transforming perceptions of the city. “It's things like the success of all the Danish TV dramas that have been exported so successfully: The Killing, Borgen and The Bridge. Related to this is that, almost from nowhere, they've now got a number of restaurants, including Noma and Geranium, which have become some of the most sought after in the world.

Founders Reception in Copenhagen, hosted by Index

“Also, over the last ten to fifteen years, we’ve seen the renaissance of Lego as a company. If you'd looked at it just fifteen years ago, you probably would assume it was on the way out, to be overcome by electronic toys. Instead, they've really gripped the opportunity of the digital world and managed to fuse astonishingly well this physical product with computer games, films, media and so forth.”

The third factor, continues Holmes, is the viable incubation and funding network that has been established in the last few years. “On the incubation side, #CPHFTW has taken it upon itself to really think of clustering, not just Copenhagen but the very south of Sweden too, and think of that whole area as one economic or one tech zone. They are organising an awful lot of events, best practice sharing and really both cheerleading and facilitating in a way which really helps the ecosystem. In addition, there are a few incubation spaces, such as Founders House and Rainmaking Loft, where founders are clustered a little like they are in East London in Tech City.

“As well as the incubation and entrepreneurial support, there are not only quite a lot of active local venture capital investors, including Vaekstfonden, SEED Capital, Northzone, Creandum and Northcap Partners, but also Index and some of the other pan-European VCs firms are doing investments in Copenhagen too. Taken together, these ingredients are creating a very viable tech ecosystem.”

CEO and founder of Trustpilot Peter Holten Muhlmann (center) in conversation with Index partner Ben Holmes (right)

And success becomes self-perpetuating, argues Peter Holten Muhlmann, CEO and founder of Trustpilot, which closed a $73.5m Series D round in 2015 and whose rise has mirrored the hub’s as a whole. “We are both benefiting from [its success] and contributing to it. It’s becoming easier to attract international talent – people seem to think it’s an exciting city -- and at the same time, Trustpilot also almost serves as a startup academy for Copenhagen. By that I mean we’ve probably made mistakes, some of which would have shut down any normal company. And we’ve been so fortunate that other things went incredibly well, which has allowed us to survive them. But the result is that I see the vast majority of Trustpilot employees, who leave us go into other startups in the city, will hopefully have learned not to repeat those mistakes.”

Your biggest limit in life is what you think is possible, and what you think is possible is based on what you see is possible [...] People don't dare to dream big enough." -- Peter Holten Muhlmann, CEO and founder of Trustpilot

Listen to Zendesk, Trustpilot and Milestone CEOs chat about their beginnings in Copenhagen and how they addressed questions about location, in a podcast moderated by The Economist news editor Leo Mirani.

Soundcloud: Founder Decisions – Location

Happiest nation on Earth.

Muhlmann also points to a number of long-term systemic factors that underscore Copenhagen’s success - not least that Denmark is a very easy place to start a business. “And I’m not sure that the ease of starting a business is something that has changed recently,” he says. “It’s always been easy – because it’s very risk free. If it doesn’t go well, society takes care of you again.”

Denmark’s famously high personal income tax rates – which are among the world’s steepest – mean that entrepreneurs are cushioned by a generous welfare safety net should their startup stutter and fail. Similarly, the country’s strong fundamentals, such as its low corruption levels, and highly educated workforce, with almost everyone online, all contribute to a stable economic environment and business culture.

For good, and sometimes for bad, the people here have a very high level of trust in our Danish society." -- Lars Thinggaard, president and CEO of Milestone Systems

And it’s that stability, argues Lars Thinggaard, president and CEO of Milestone Systems -- the market-leading manufacturer of open platform IP video surveillance software, which was acquired by Canon in 2014 – coupled with the Danish government's tax and spend policies in areas such as education, which help account for the fact that the Danes have repeatedly been named by the UN as the happiest nation on Earth, despite paying some of the highest taxes. “For good, and sometimes for bad, the people here have a very high level of trust in our Danish society,” he says. “When that’s combined with having the lowest levels of corruption, it helps explain why some of our US partners are talking to us about setting up their subsidiaries not in London or Amsterdam, but in Copenhagen.” Thinggaard also singles out the city and national government’s infrastructure projects, which among other things, have seen Copenhagen’s airport become Scandinavia’s leading hub (by passenger numbers.)

Similarly, he praises the country’s approach to higher education. “From an engineering point of view, we have the DTU (Technical University of Denmark), which is one of the leading engineering institutions in Europe, while Copenhagen Business School is now one of Europe’s largest business schools. For tech startups that means there are a lot of very good candidates, in both management and engineering, that you can draw from to drive a startup company forward,” he says.

Global prominence.

Copenhagen’s Rainmaking Loft, which opened in 2015, is about a 45 minute walk along the waterfront from Founders House. Located in a stylishly refurbished former naval building -- built in the 1880s -- from where sailors collected their uniforms before going to sea, this important addition to Copenhagen’s startup ecosystem now hosts over 300 resident entrepreneurs from around 80 startups.

In its report CITIE: The Nordic Analysis (prepared for Index in November 2015), the UK innovation charity Nesta found much to applaud in Copenhagen policymakers’ approach to technology, innovation and entrepreneurship. However, it also noted that despite “isolated areas of good performance” – including its “global prominence as a tech cluster” – the city lagged some way behind its competitors Stockholm and Helsinki, and urged it to increase its support for the startup scene, described as “the cornerstone of economic activity in the city”.

Rainmaking Loft’s MD, Kristian Justesen is sanguine about the progress Copenhagen has made over the past few years, believing that the city is starting to gain ground on frontrunners Stockholm and Helsinki. However, he also argues that Danish policymakers have a long way to go before making a palpable difference to Copenhagen’s startup community.

When asked what he would like to see introduced, he cites UK government initiatives such as the Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) and Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme (SEIS), which offer tax breaks to investors in early stage companies. “But it’s hard to imagine similar instruments put to use in Denmark,” he says ruefully. “Also, here, there are really high taxes if you want to offer stock options to your employees. So it’s not that normal to do that in Denmark, although there’s increasing political debate about the topic.

“What works quite well in Sweden is that when you have a successful startup – a Spotify, for example – you then create a lot of new business angels, because a lot of the employees who owned stock in the company, after an exit, then become quite wealthy. And that fuels the whole ecosystem, because suddenly instead of just having one or two really wealthy guys, you have maybe 50 quite wealthy guys, meaning that you have far more people who can reinvest some of their capital into the ecosystem – we don’t have much of that here.”

Others, are more blunt about the situation – Thygesen says the Danish government, alongside many other European governments, simply “don’t get” startups. By way of an example, she cites some of the issues companies like Uber and Airbnb have had in Europe. “I wish we saw a little bit more vision and leadership from politicians, because Europe is falling a little bit behind sadly,” she claims. “We're still resting on our laurels and we need to be more visionary if we want to continue to compete. In general most European politicians don't understand startups. Here in Denmark, apart from a couple of good ones, they don't either.

So why is the attention coming from the UK politicians and US diplomats, but not from their Danish equivalents? It’s a 20 minute walk from parliament to where we’re sitting. It’s a lovely walk by the water, too, so there’s no excuse." -- Tine Thygesen, co-founder of Founders House

“When I started at Founders House five years ago, we couldn't get politicians to turn up to anything. And still today we've only had one Danish politician come to Startup Village. But we recently had a visit from the UK chancellor of the exchequer George Osborne. He had two meetings in Copenhagen – one with the Danish finance minister, the other was here. American ambassadors have been here regularly too. So why is the attention coming from the UK politicians and US diplomats, but not from their Danish equivalents? It’s a 20 minute walk from parliament to where we’re sitting. It’s a lovely walk by the water, too, so there’s no excuse.”

Tech Heroes.

For #CPHFTW’s Malling, the political establishment has done far too little to celebrate Denmark’s top tech stars and turn them into household names. “[Tech heroes] are just not known to the average Joe in Denmark,” he says. “Take David Helgason of [multi-platform games engine] Unity Technologies, for example -- for most people, it’s like ‘What’s Unity?’ We have the [recently acquired fitness app and website] Endomondo founders here in Denmark, who became a bit famous for a while, just because a lot of money changed hands. [The media and government] still celebrate the money, but not the hard work and ideas.”

Promotion aside, the real problem, continues Malling, is that while the government has established some good institutions – such as SEED Capital, a semi-public VC company and the Danish Growth Fund – there’s a lack of overall strategy and collective will to push Denmark further in IT in general and startups in particular. “I was just interviewed for a local newspaper and I said I dare any Danish politician to tell me what a startup is,” he says. “They just don’t know.”

So given these issues, what are the chances that fast-rising Copenhagen can climb into the next tier of international tech hubs, challenging, say, London or Berlin? The reality is that Denmark, with a population of just 5.6m, will always be limited by its size, forcing any ambitious startup to consider leaving the country as soon as they start to grow, says Milestone’s Thinggaard. “You can find examples of Danish companies who have built a consultancy business on top of their technology, and had success locally, but that’s extremely rare. So it’s by nature that you’re forced outside of the boundaries of the country just to succeed.”

As a consequence, many home-grown hits – such as Just Eat or Zendesk – have come to be viewed almost as international rather than ‘Danish’ success stories. Zendesk, for example, though Copenhagen-born, is now headquartered in San Francisco -- a result, says the company’s co-founder and CTO, Morten Primdahl, of their initial struggle to raise investment in Denmark, when the company was founded. “Times were different in 2007 -- you could not get any investment in Copenhagen. We tried very hard, but there was no startup community here then. So we had to go elsewhere, to get closer to investors and also to our customers. These days the ecosystem here is fantastic. If you start something in Copenhagen today, you probably would want to build your first product here and see your first revenue, and then go to San Francisco or Silicon Valley and establish yourself there, as you get to your Series A or Series B, because there still really is a world of difference between Copenhagen and Silicon Valley in that respect.”

Zendesk co-founders in front of their Copenhagen office

Trustpilot’s Muhlmann sees Denmark’s size as an “enormous issue” for any fast-growing Danish startup. “Copenhagen is a fantastic place for a company when you’re say 20-50 people -- even up to 100. Then you really start to feel the shortcomings of being here. So you need to be very aware of that and to plan carefully for what you’re going to do, when you want to hit international scale.” (Trustpilot’s own approach to this has been to open six global offices, including in London and New York. “So rather than moving our HQ, we are becoming more distributed,” he says.)

But, argues Muhlmann, it’s not simply its size that stands in Copenhagen’s way of reaching the sort of startup velocity seen in London or New York, let alone Silicon Valley. It’s partly down to what he terms “critical mass”. “If you take Berlin, it has much more international talent, much lower wages, and much better access to capital [than Copenhagen],” he says. “London has higher wages, it’s incredibly expensive, but it has enormous access to capital and talent.”

Even Stockholm, with more companies that have made it globally, is a couple of phases further down the road than Copenhagen, he continues. “That means they have more people who are experienced in the late stages of a business. And they have a bigger network, which means it will be easier for Stockholm founders to go all the way. We’re still trying to create a series of companies here which have gone all the way. You won’t see a lot of examples of that in Copenhagen, so that needs to build up and that takes time.”

There are a couple of things the Danish government can do to speed things up if they wish, he says. “If they wanted to help the startup community, they’ve got to look at the ease of bringing talent into the country. And the ease of rewarding people with equity. Those two things would make a huge difference. But due to the political situation, and the way society is here [with regard to taxes], I’m very certain that will not happen.”

Zendesk’s Primdahl agrees that political willpower will be crucial if Copenhagen’s to build on its success, arguing that failure to make it easier to import foreign talent, in particular, will carry major risks. (He also argues that a key to longer term success is to start thinking of programming as a core competency in the educational system early on, in order to help improve the diversity and the number of people who can have a successful career in technology.) “Currently it’s fairly easy to hire people [locally] in Copenhagen. But looking at the growing number of investments here, eventually that will no longer be possible. As things stand, the danger is that when we start to run out of talent, then companies will start ask themselves whether they should move development out of the country. If that happens, then we’re back to square one.”

Zendesk co-founder and CTO Morten Primdahl in Copenhagen

Muhlmann, who describes himself as “cautiously optimistic” about Copenhagen’s future, is at pains to stress that the situation is “far from bad” in the city. “Just because I think Copenhagen can’t become a bigger startup hub than Berlin or London, doesn’t mean that we can’t do a lot of great things here,” he says, adding: “This city will go on creating lots more great startups.”

Posted on 20 Apr 2016

Published — April 20, 2016