What to Expect in 2020

As 2019 draws to a close and we’re about to embark on a new decade, our partners discuss the biggest trends that happened this year and their perspectives on what we should expect in 2020.

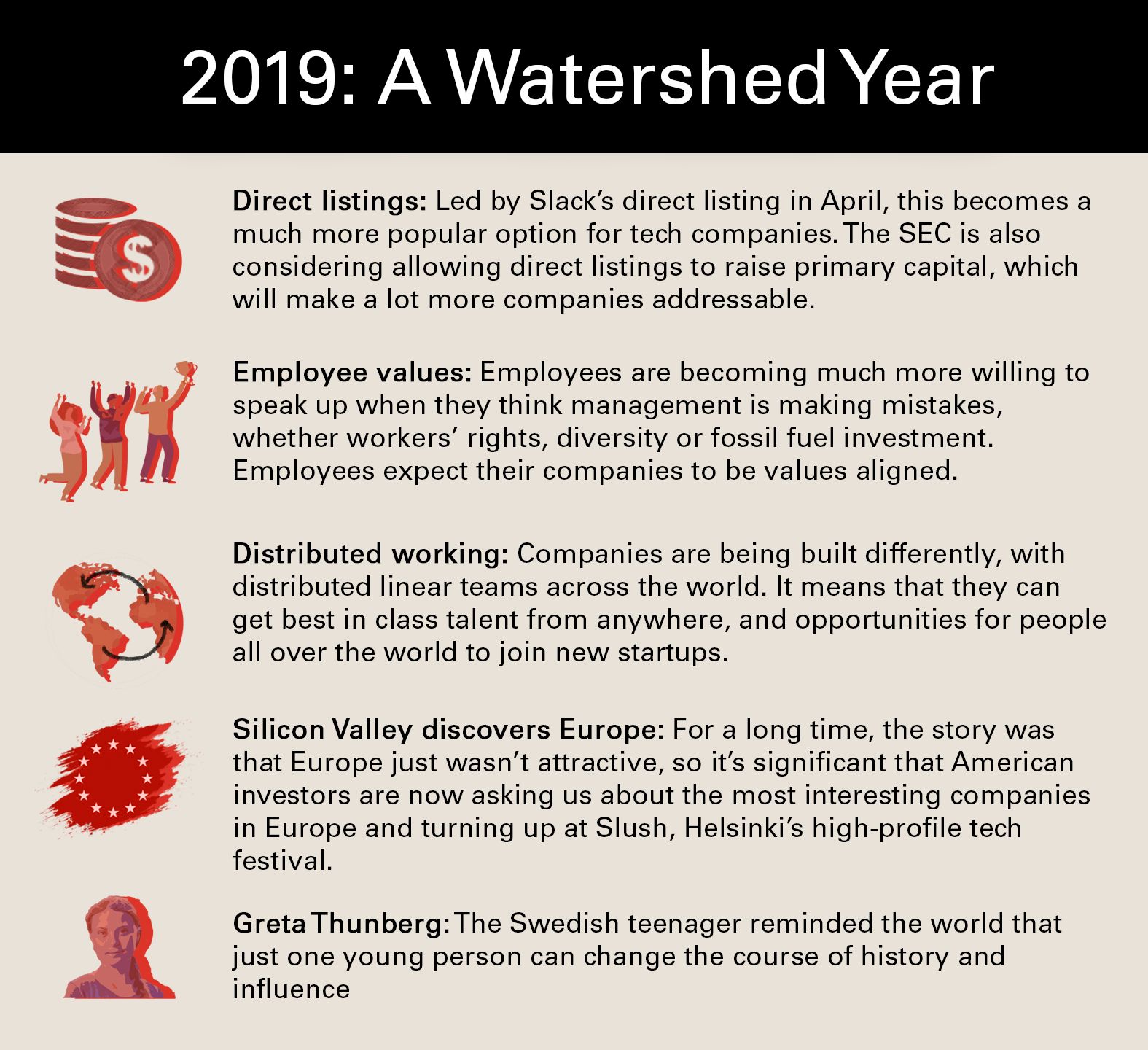

In retrospect, it was no surprise that 2019 turned out to be a watershed year for the technology industry. On the one hand, we continued to celebrate the positive impact of technology from successful IPOs and public listings, to remarkable advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), while increasingly focused and mature tech startups benefited millions of customers around the world. Yet, on the other hand, some of the biggest and most successful technology firms faced intense scrutiny over their business models, with questions asked in Congress and the media over their privacy policies, unprecedented influence over elections, and the ethics of AI.

From high growth to solid business fundamentals

We entered 2019 with high hopes for blockbuster IPOs like Uber and WeWork. Yet as some of these big companies began to initiate the IPO process and started trading, it became evident that the mood had shifted; public investors were cooling on grand visions of future growth, and instead moving towards tech companies with solid business fundamentals and attractive margins. For companies with robust business models, capital efficiency, and large addressable markets, that was good news — and was reflected in the market response to IPOs like Datadog, Zoom, and Peloton, among others.

Mike Volpi agrees that the public markets have pushed back against the ‘build it and they will come’ business models that seemed to epitomize the 2010s. “VCs tend to invest in support of a vision,” he says. “They see something grand on the horizon and are compelled to invest in the hope of discovering the next Google or Facebook. Early-stage venture investors have always believed in those principles, but lately even late-stage investors have subscribed to a similar thesis. There has been a huge amount of money plowed into companies with big visions but unclear economic models. One of the significant challenges of excessive capital deployed without financial discipline is that these companies never develop sustainable business models. Unfortunately, for them, the music stops post IPO; public markets do look for that sustainability and eventual profitability in businesses.”

This stabilization, Jan Hammer believes, is more significant than the problems of companies like WeWork, which was forced to cancel its high profile IPO in September, and Uber, which announced a $5bn loss in Q2 that took 10% off its share price just three months after it went public.

“Public investors are now seeking value and profits over growth and losses,” Hammer explains. “In the case of WeWork, there was clearly a demand for flexible corporate accommodation, and an entrepreneur created a product that met that need. On the face of it, that appears to be a phenomenal product-market fit.” The problem was that a technology valuation was being attached to what was really a real estate company, so instead of 10X revenues, 2X revenues would have been more realistic. “The conclusion is that there’s a fair amount of momentum investing that just hasn’t been discerning enough to unpick the fundamentals of certain companies. It’s unhealthy because the markets live on perception, and perception of underperformance is potentially worse than underperformance.”

Despite this wake-up call, the wider industry has avoided a more fundamental catastrophe this year and points to a kind of resilience, Hammer says. “The problems at WeWork and Uber have been isolated events, and across tech, people are working hard and delivering results, so I’m optimistic at heart.”

Sarah Cannon sees this as a long-overdue discernment driven by the public market. The refocus on strong business models has shown up in the dramatic increase in pricing for private companies being started in attractive sectors, something Cannon summarizes as a shift from ‘relative’ to ‘absolute’ valuations. “Historically, companies used to be valued based on a multiple on revenues. Today, with many new funds trying to get into competitive deals, investment firms are offering prices that will get them their target return based on the estimated size of the market opportunity, and an extrapolation of value rather than current business traction. This is why, at the first signs of a company breaking out as the leader, early-stage startups are valued up to four years ahead of their current metrics.”

Fintech: from strength to strength

It was yet another strong year for fintech. And while it might seem that we’re at the height of the fintech hype cycle, there’s still a big opportunity for innovation. The $10bn-$30bn valuations of some fintech businesses are not large compared to traditional financial organizations. And as the sector matures, we’ll see the sector leaders build far bigger valuations, while some less robust competitors will fall by the wayside.

Cannon says she remembers an email landing in her inbox from Charles Schwab, announcing it was eliminating fees for trading. Reading The New York Times later, she realized that it was likely Robinhood that had pushed Schwab to change its model. “That a new entrant like Robinhood could drive one of the biggest US banks to change its business model is just astounding,” Cannon says. “Oftentimes it can take startups a long time to impact a market dominated by massive incumbents, yet Robinhood did so in a few short years. They set out to democratize financial institutions and executed extremely fast.”

Fintech offers some great role models for disciplined, profitable businesses with huge potential for growth, Hammer explains. Adyen has become one of the stars of the European tech scene since its impressive IPO in June 2018. “We need this kind of role model because it demonstrates that being profitable and having healthy cash flows is consistent with growth, and that is a sound business model, a defensible product and huge growth market,” he says.

A new generation of companies is emerging in European fintech in the wake of Adyen’s success. Paris-based Alan, which is starting to transform the private health care system, is one such example. “A lot is written about how healthcare systems are broken because demand is infinite, but so much depends on the relationship between patients, providers, and payers,” says Hammer. “There’s a huge opportunity to rebuild that system around the flow of data, and Alan is building a great business while maintaining a low burn rate.”

The reality of artificial intelligence

AI moved to a whole different level of public awareness in 2019. “Even two years ago it was something cool that researchers at universities and big businesses were thinking about,” says Volpi. “Now every company has a budget and a need for AI or ML in some way.” He points to the data training company Scale.com, the self-driving technology firm Aurora, and Instabase, which provides business process automation for businesses — all of which are benefitting from sophisticated AI. “Demand forecasting, anomaly detection, predictions, security and fraud detection,, or security cameras in a convenience store — these are all new and interesting pathways for AI. The whole theme of AI and ML has really mainstreamed.”

Cannon argues that we also have to be realistic about what AI really can do. “There’s so much it still can’t do — such as expressing emotions, so I think the fear of bots taking over the world is a little overstated. In the near term AI is going to take some immediate tasks off our plate, but in no way can it perform complex surgery or negotiate with China on trade tariffs.”

Data-centric businesses will thrive in 2020, Hammer says, as a new generation of startups develops data intelligence and proprietary data sets for every industry, from real estate and finance to transportation and energy. Data intelligence will spur a new wave of innovation in the same way the internet and the app economy has done, and it will be in data intelligence where we will see some of the most effective commercial applications of AI.

As it becomes more widely adopted, AI is facing complex challenges, including bias and accountability, Volpi argues. “An experimental AI system is even being used to inform sentencing recommendations for judges. But AI works through training which means using historical data, and if there’s human bias in the sentencing data then the system will learn that bias. As AI moves into the mainstream, these complicated challenges around bias and privacy are ones that will need to be addressed.”

Many of the problems raised by AI are so new that they aren’t being addressed by either traditional ethics or computer science training. Cannon argues that there’s a need for more engineers to start incorporating ethics as part of their curriculum, so they can design from first principles with the societal impact in mind. “Doctors have a Hippocratic oath they commit to when they embark on their profession, so should engineers have an equivalent oath to uphold specific ethical standards?” she contests.

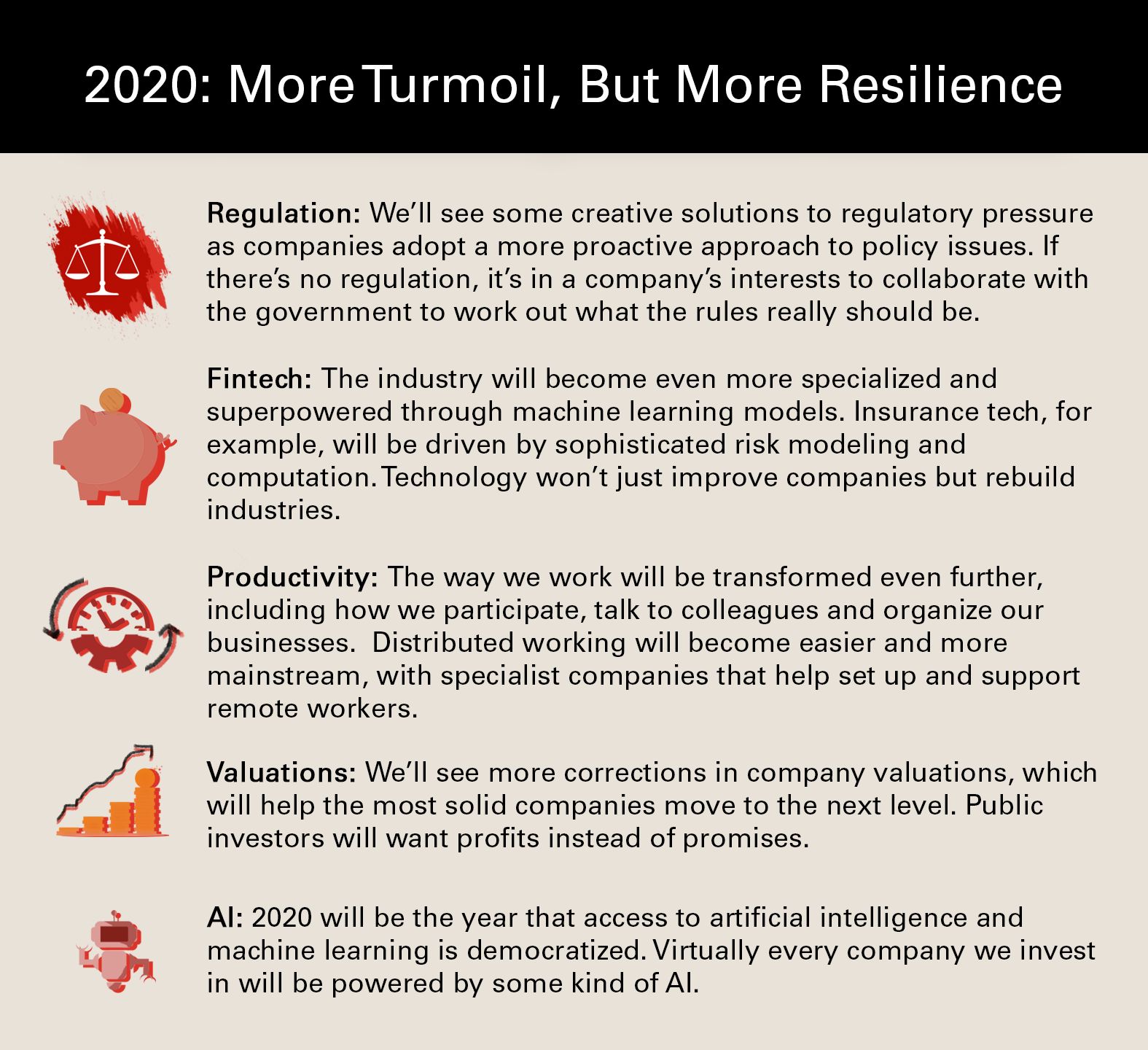

More turmoil, but more resilience

If 2019 was the year technology was shaken up, then 2020 could be more so. Volpi says he’s expecting one of the most tumultuous years in memory. “There’s an important election, an impeachment, and yet more Brexit, and that will all have some effects on the market. Maybe it’s a year where we see some corrections in valuations.”

Cannon views 2020 as the beginning of a new era for competition policy. Although there has been a lot of discussion about anti-monopoly, she expects regulators to finally catch up. “The zeitgeist is about independent startups driven by customers, employees, investors and founders alike, all looking for alternatives to big incumbents in these huge markets. And that means the long shadow cast by GAFA — Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon — will slowly be brought into the light.”

Volpi points out that in the past decade venture capital itself has changed. “There’s been a super interesting changing of the guard,” he says. “Some of the most famous firms of 2010 you just don’t hear about anymore, while Softbank built a $100bn fund. That’s a mobile operator from Japan, and look at what they’ve become. Technology has changed the world, and the world has changed technology, too.”

Hammer is characteristically upbeat. “Series A investments are our bread and butter, and in early-stage investments, I see a lot of secular stability,” he says. “That’s not driven by a change in government, politics or interest rates — it’s driven by education, by encouraging entrepreneurs, by good role models, and by the ecosystem of incubators and accelerators.” Hammer describes how there are many more startups now than ten years ago, and that the quality of those companies is much higher, too.

“The unpredictability factor has risen, certainly, but the flip- side is that everybody seems remarkably calm because we’ve incorporated all this uncertainty and volatility,” says Hammer. “The world is in a fragile place on a macro level, but I think of the millions of regular people who contribute optimistic units of macroeconomic output. As long as we keep going to work every morning, it will be fine.”

Published — Dec. 19, 2019